The Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) is one of the World's most destructive viruses, and it is estimated that over 35 million people have died from HIV Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) since its discovery in the 1980s (UNAIDS, 2014). HIV AIDS has proliferated to become the leading cause of death within sub-aharan Africa, and a global health problem (Rao et al, 2006; World Health Organization, 2015). Currently, over 100,000 people are known to be living with HIV within the United Kingdom (UK); approximately 6,000 new cases are diagnosed each year and there is an unrelenting rate of HIV transmission amongst men who have sex with men (MSM) (Skingsley et al, 2015; Terrence Higgins Trust, 2015). Therefore, paramedics are more likely to encounter patients who have HIV within their clinical practice; they should feel able to engage in safer-sex conversation, signpost higher-risk patients to HIV testing facilities or services, encourage adherence to HIV medication, and appropriately recommend post-exposure prophylaxis services as part of a multifaceted HIV prevention strategy. This article will provide paramedics with an overview of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus, although it will specifically consider HIV-1, which is the most prevalent sub-type of HIV within the UK population.

Epidemiology

Each year approximately 6,000 new cases of HIV are diagnosed within the United Kingdom, adding to over 100,000 people who are known to be living with HIV (Skingsley et al, 2015; Terrence Higgins Trust, 2015). It is difficult to quantify the exact number of people living with HIV, as almost one in five people who have HIV are unaware of their positive HIV status, which is a public health concern (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE], 2014; Skingsley et al, 2015). HIV is most common amongst men who have sex with men (MSM) within the UK, with around 1 in 18 MSM being HIV positive; rising to 1 in 8 within areas of London (National AIDS Trust [NAT], 2014). Black-frican people have the second highest incidence, and account for two-thirds of HIV infection within the heterosexual HIV positive population, with incidence of 56 per 1000 aged 15–59 years (Public Health England, 2014). HIV is notably more common in males than in females, and women who have sex with women have the lowest rate of HIV transmission (Kwakwa and Ghobrial, 2003).

HIV can be transmitted when the blood, semen, pre-ejaculate fluid, vaginal mucus, anal mucus or breast milk of a person with HIV enters the body of an uninfected person. However, it is most commonly transmitted through:

HIV does not thrive outside the human body, and is seldom transmitted through saliva or non-blood contact, which is not well known (Simon et al, 2006: Public Health England, 2014). Therefore, it is unlikely for ambulance clinicians to be exposed to a significant risk of HIV transmission within their routine clinical practice (Health and Safety Executive, 2016).

HIV and AIDS

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (or HIV) is a retrovirus that specifically targets CD4+ T Lymphocyte cells within the immune system of an infected host. CD4+ T cells ordinarily formulate the immune response to infection by identifying foreign antigens and then generating an antibody response. These cells quickly become ineffective in patients with HIV, left untreated their immune system deteriorates to become dangerously weak, and they become susceptible to severe opportunistic infections from organisms that would ordinarily be harmless. HIV attaches to receptors on the CD4+ T cell, and once fused, incorporates RNA into the host cell's DNA through the process of reverse transcription. The newly-infected CD4+ T cell then replicates its DNA to reproduce huge numbers of HIV within the host, which are released into the bloodstream with cascade effect (Touloumi and Hatzakis, 2000; Faulhaber and Aberg, 2009).

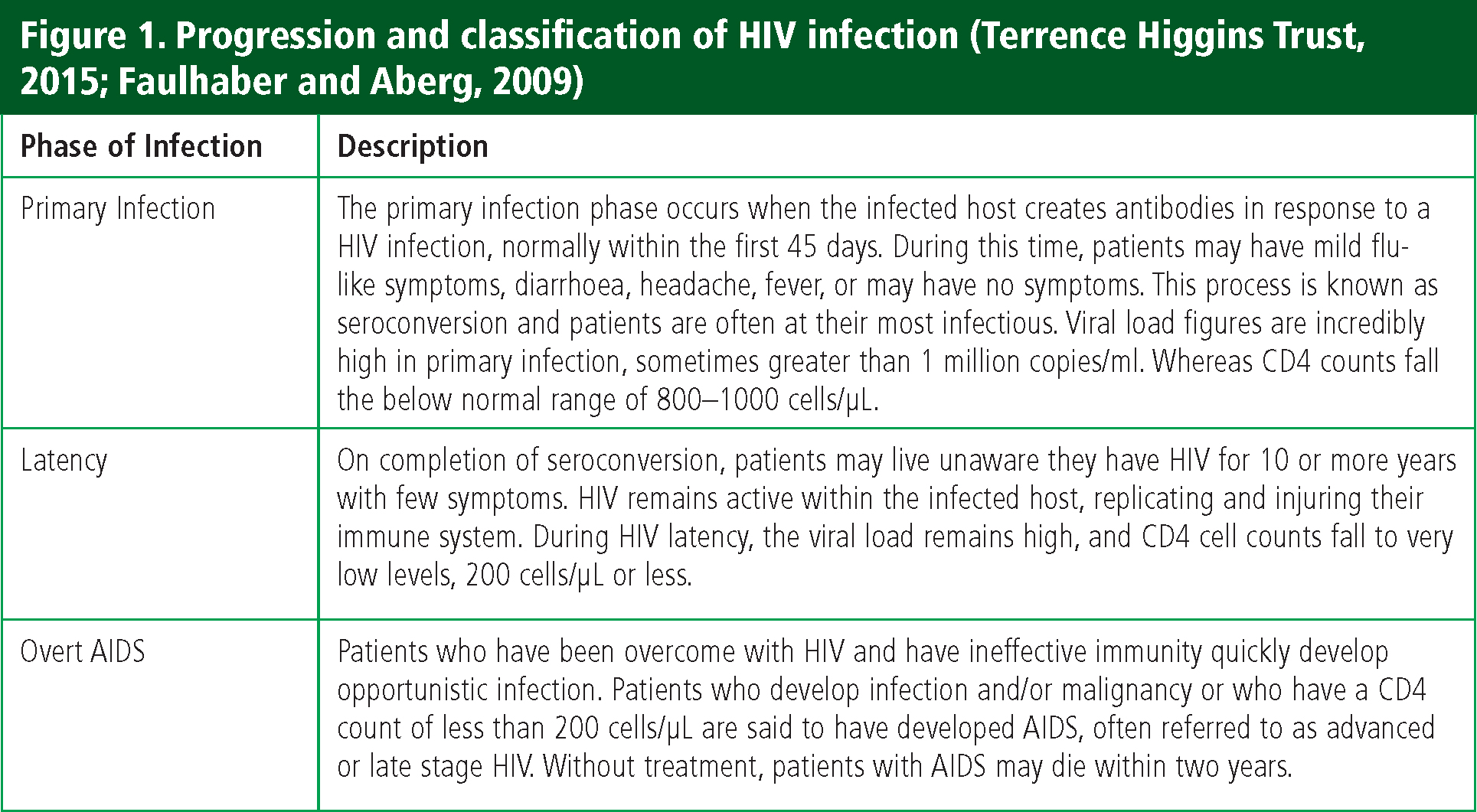

The severity of HIV infections can be measured by the amount of virus found within the host, commonly referred to as the ‘viral load’ figure (Terrence Higgins Trust, 2016). Patients with a high viral load have overwhelming HIV infection, which causes rapid CD4+ T cell destruction and a low ‘CD4+ count’ (<350 per microliter) (Faulhaber and Aberg, 2009). HIV is separated into three phases of infection, known as the primary infection phase, latency phase and the overt AIDS phase, explained in Fig. 1 (Simon et al, 2006; Faulhaber and Aberg, 2009).

Acquied Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) is caused by infection with HIV, which, if left untreated, leads to severe immune system compromise with subsequent development of opportunistic infection, malignancy and nervous system degeneration. With ineffective immunity patients develop persistent and recurrent infection, and illnesses such as tuberculosis (TB), pneumonia and severe fungal infections become prolific. Advances in HIV treatments have reduced the incidence of AIDS within the UK, though it remains a significant burden in many parts of the World (Faulhaber and Aberg, 2009).

HIV testing

HIV testing is fundamental in the effort to reduce the rate of transmission within the UK. It is known to influence sexual behaviour, hasten access to specialist HIV treatments and reduce the likelihood of unwitting transmission after receiving prompt HIV diagnosis (British HIV Association, 2008). Currently, almost half of all new HIV infections are thought to originate from patients who are unaware of their positive HIV status, which leads to late clinical diagnosis (NAM, 2013). These patients encounter mortality rates up to ten times higher than patients who receive prompt HIV diagnosis and achieve early virological suppression, which poses a greater risk to public health (NAT, 2015; Skingsley et al, 2015). Paramedics can help to reduce the number of people who receive late diagnosis and prevent unconscious HIV transmission through accurate and informed signposting to HIV testing facilities. HIV testing is a cost-effective component of a long-term HIV prevention strategy, meaning tests are becoming increasingly accessible and remain relatively cheap. Patients can now access HIV tests within primary care centres, community settings, Lesbian Gay Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) Pride events, and home testing kits (Manavi et al, 2012).

‘HIV is separated into three phases of infection, known as the primary infection phase, latency phase and the overt AIDS phase’

Despite the undeniable benefits of HIV testing, it is not sensible to test every patient for HIV whenever they have contact with a healthcare professional (HCP), but certain patients should be offered a test. The British HIV Association (2008) offers the following guidance to healthcare professionals, including paramedics, to help identify patients who disclose social or sexual behaviour that is considered higher-risk of HIV acquisition. It includes:

Likewise, patients who are pregnant, commence dialysis or become blood donors should receive routine testing (British HIV Association, 2008).

HIV treatment

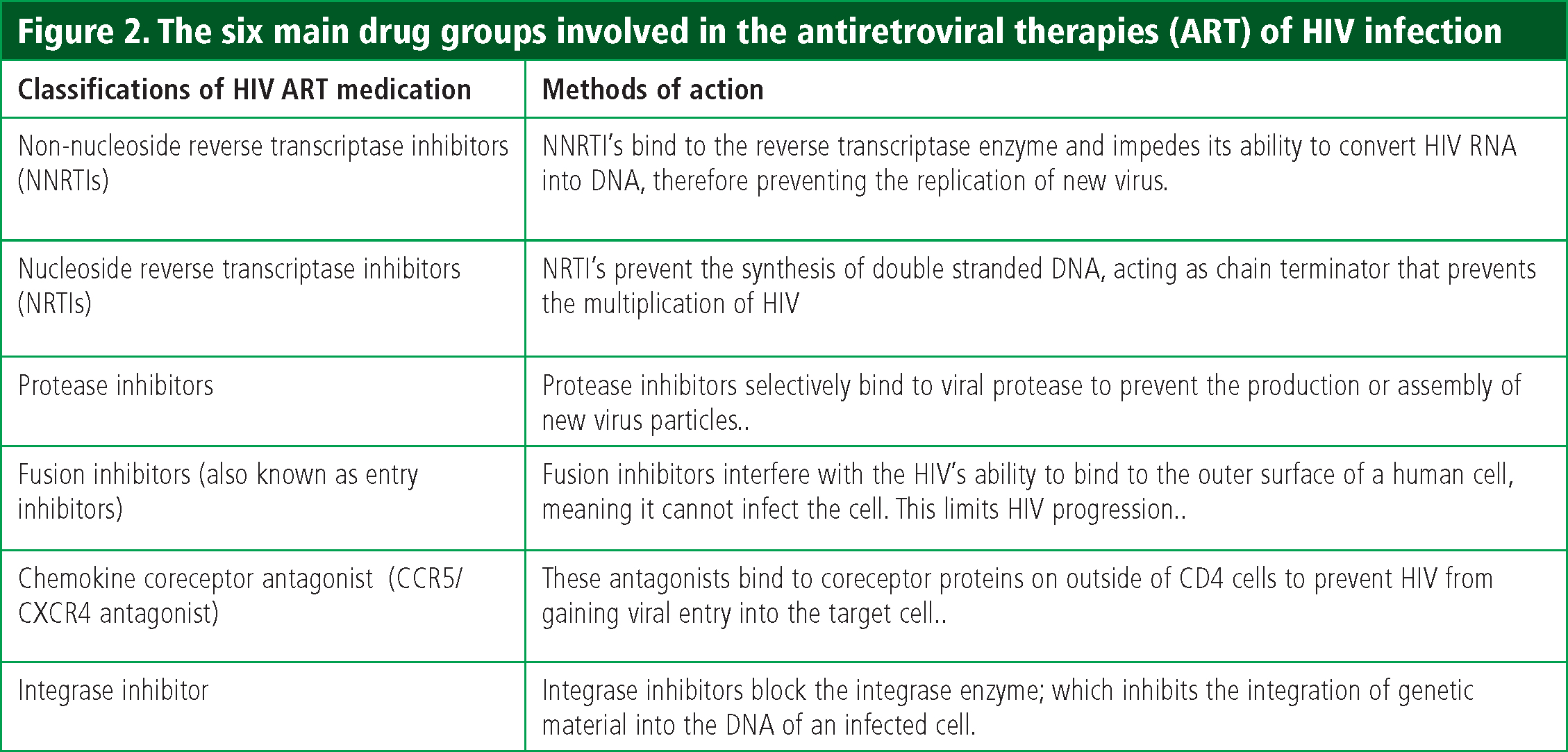

Patients with HIV require lifelong treatment as there is no known cure and no preventative vaccine. The discovery of antiretroviral therapy (ART) and the subsequent use of ART in HIV treatment is considered one of the biggest achievements in modern medicine; which remains an effective treatment option for HIV infections (World Health Organization, 2016). ART aims to reduce the host's viral load to undetectable levels (<40 copies per microlitre) to inhibit HIV replication and limit immune system injury to avoid the disease progression. It is usually prescribed as combination therapy (CART), which has greater viral suppression. There are over 20 different types of ART treatments, which are separated into six different categories and presented in Fig. 2.

The British HIV Association (2015) recently updated their treatment guidelines for primary and chronic HIV infection, with significant changes to the use of antiretroviral therapy following initial diagnosis. Antiretroviral therapy should begin as soon as possible following diagnosis, regardless of the host's viral load figure or CD4+ count, to achieve prompt virological suppression, and to aim for a healthier immune status. It is expected that patients will benefit from fewer HIV and non-HIV related illnesses following this change of guidance, and they will also be less likely to transmit HIV during this early phase of illness (Churchill et al, 2015; Skingsley et al, 2015). A robust randomised trial published by the INSIGHT START study group confirmed many benefits of early ART therapy in HIV patients, adding to the growing evidence-base (Lundgren et al, 2015). Previously only patients with either a low CD4+ count (<350 per microlitre); overwhelming infection; co-infection of Hepatitis B or Hepatitis C; HIV related neurological involvement or non-AIDS malignancy requiring chemotherapy or radiotherapy immunosuppression were recommended to receive ART (Williams et al, 2014).

It is recommended that patients who are naïve to ART start with a combination of NNRTI and NRTI and a protease inhibitor, such as Tenofovir and Emtricitabine with Atazanavir (Williams et al, 2015). Combination therapy is more successful at achieving prompt viral suppression, and there is effort to incorporate these treatments into single tablet medication with lesser pill burden to improve medication adherence. An example is Atripla; a medication containing efavirenz, tenofovir and emtricitabine contained within one tablet, which demonstrated greater medication adherence compared to multiple tablet ART. Refining treatment occurs on a case-by-case basis to ensure greatest HIV suppression, treatment adherence and allow for prompt intervention in cases of treatment failure (Volberding and Deeks, 2010; Williams et al, 2014; Rao et al, 2013). The most common medication that paramedics will encounter is Truvada, a tenofovir and emtricitabine co-formulated into a single tablet.

Paramedics should encourage patients to become meticulous with their HIV medication regimes, aiming to achieve virological suppression and have a functioning CD4+ status. Patients who have high viral loads are the biggest risk factor for HIV transmission, whereas patients with undetectable viral loads are extremely unlikely to pass on HIV, supporting the need for ART compliance (Skingsley et al, 2015). The Partners of People on Art – A New Evaluation of the Risk, or ‘PARTNER’ study, explored HIV transmission between couples where one partner is on suppressive ART, who engage in condomless sex. The authors considered over 58,000 condomless sex acts between heterosexual and homosexual couples in 14 European countries, and found no evidence of HIV transmission between couples that had undetectable viral loads (Rodger et al, 2016). In summary, this study supports the use of ART as a preventive technique to reduce the rate of HIV transmission.

HIV monitoring

The effectiveness of individual HIV treatment is monitored by HIV consultants at specialist HIV clinics, or genitourinary medicine (GUM) clinics, where HIV viral load and CD4+ cell counts are reviewed. Patients usually attend clinic at three-, four- or six-monthly intervals where they undergo tests to investigate their viral status and receive viral load monitoring, which is known to be the most accurate indication of treatment success (Ford et al, 2015). The trends of a patient's viral load and CD4+, monitored once a year for stable patients, allow healthcare professionals to consider if their treatment is effective, or whether additional or alternative therapies are needed. It also allows consideration of the unpleasant side effects often associated with ART, such as gastrointestinal disturbance and bone density reduction. Paramedics may want to consider these values to realise the impact of an HIV infection on a patient's immunity, and their ability to overcome non-HIV related illness and infection.

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP)

Paramedics may have already heard of post-exposure prophylaxis, sometimes also called PEPSE, therapy during their infection prevention and control training for needle stick injuries. PEP involves the administration of antiretroviral therapy medication to inhibit infection of HIV following an episode of HIV exposure; it is available through sexual health services and acute hospital services following health assessment. PEP plays a key role in the HIV prevention strategy (Public Health England, 2014). The British HIV Association (2008) recommend patients who have sexual exposure to HIV receive PEP within the first 72 hours, or following a contaminated needle stick injury from a higher-risk patient (Benn et al, 2011; Public Health England, 2014). It typically involves the prescription of ART for 28 days, although many patients also receive anti-diarrhoeal and antiemetic medication to overcome the associated side effects and improve concordance. Patients should receive blood testing during their initial consultation, and require three-month follow-up for a more definitive and accurate HIV test. At the same time, patients who access PEP following sexual exposure to HIV may also benefit from referral for risk-reduction services and wider sexual health screening (Benn et al, 2011). PEP is most effective within the first 72 hours following HIV exposure, and patients who report such exposure should receive prompt PEP treatment.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)

Pre-exposure prophylactic treatment (PrEP) involves the use of antiretroviral therapies to reduce the likelihood of HIV transmission prior to HIV exposure. PrEP is not currently available on NHS prescription, although it is likely to be included in future strategy to reduce transmission and there is a convincing argument for PrEP to be readily available to patients who request it (Terrence Higgins Trust, 2015). Patients most likely to require PrEP therapy include (Terrence Higgins Trust, 2015):

Like ART used in HIV treatments, there have been studies to compare the efficacy of singular and combination PrEP treatments; the results support that combination PrEP is also more effective than singular drug treatments (Thigpen et al, 2012; Choopanya et al 2013). The most common ART combination used for PrEP is Truvada, tenefovir and emtricitabine co-formulated into a single tablet. There is growing evidence to support the use of PrEP in reducing HIV transmission, and the World Health Organization (2014) believes PrEP therapy could obviate one million new infections over 10 years.

Earlier this year, data from the PROUD study was published (McCormack et al, 2016); this study provides a credible argument for additional PrEP therapy for men who have sex with men, to strengthen current avoidance methods. This randomised trial studied over 500 participants to demonstrate PrEP can be effective in reducing HIV transmission within this high-risk group, with no increase in other sexually transmitted infections (McCormack et al, 2016). Pre-exposure prophylaxis should not be seen as an alternative to safe sex, and should form additional methods of protection for patients who find condom use difficult. Pre-exposure prophylaxis is now available on prescription in many neighbouring European countries.

HIV awareness

Public health campaigns raise awareness of HIV and AIDS and unite in the fight for a cure. National HIV Testing Week aims to increase the number of MSM and black African men who take a HIV test, in an attempt to identify undiagnosed HIV infections. Similarly, World AIDS day is celebrated on 1st December each year to raise awareness of the global AIDS fight, and raise funds to tackle this issue all year round (HIV Prevention England, 2015; National AIDS Trust, 2015). Social media is flooded with HIV content to engage in HIV conversation and education, such as the ‘It Starts with Me’ campaign that promotes HIV testing and regular condom use (Terrence Higgins Trust, 2015; HIV Prevention England, 2015). Although many ambulance trusts have developed lesbian gay bisexual and transgender (LGBT) support networks who engage in this online conversation, this is often limited to members who are already well-informed. Ambulance trusts can increase their impact in HIV prevention by providing guidance to frontline staff on HIV, and encourage the attempt to make ‘every contact count’.

Taking a sexual history

The assessment of a patient's sexual history allows paramedics to identify patients who are at risk of HIV, sexually-transmitted infections (STI) and demonstrate high-risk sexual behaviour. Sexual history may be considered within the genitourinary system review, to create opportunity for patients to disclose symptoms that may have been overlooked, and receive the relevant follow-up (Brook et al, 2013). There is evidence to suggest that the successful treatment of STIs can reduce the likelihood of HIV acquisition, emphasising the need for regular sexual history assessment (Jones and Barton, 2004). While most paramedics are confident in their history taking ability, it is recognised that many allied healthcare professionals do not feel confident to discuss sexual activity, condom usage and sex between men (Tomlinson, 1998). Sexual history should consider a patient's age, risk, gender identity and marital status, but paramedics should not presume that a patient has a specific sexual orientation or attitude towards sex (Pakpreo, 2005). Paramedics should not assume that all male patients are heterosexual, and such heteronormative attitudes are potentially offensive and unhelpful. The disclosure of sexual orientation or sexual behaviour is very personal, and paramedics are reminded that patient confidentiality must be adhered to (Bickley and Szilagyi, 2009).

Safer-sex conversation

The use of condoms during sexual intercourse is the single most effective intervention to prevent HIV transmission, and should form part of health promotion activity for paramedics. To leave safer-sex conversation to clinicians within specialist sexual health services would disregard the millions of consultations that take place across healthcare. The ‘Every Contact Campaign’ (ECC) emphasises the huge opportunity for health promotion activity to influence a patient's physical and psychological wellbeing, regardless of their point of access or professional identity (Clutterbuck et al, 2012; Bailey et al, 2014). Healthcare professionals already collectively attempt to help people to stop smoking cigarettes within the UK, and such unity could be expanded to include HIV prevention and safer-sex advice when appropriate. To be most effective, paramedics should provide accurate and informed advice regarding safer sex; they should make the following recommendations (Clutterbuck et al, 2012).

HIV stigma and health inequality

People living with HIV are known to experience stigma, discrimination and inequality within healthcare, worsened by uninformed healthcare professionals and poor understanding of HIV disease (Stonewall, 2015). The LGBT community are most affected by HIV within the UK and they frequently experience negative attitudes when they access health and social care, which has a negative impact on their physical and psychological well-being (Stonewall, 2015). LGBT discrimination is against the law within the UK and is completely unacceptable within a modern healthcare system, and such prejudice demonstrates professional misconduct (Peate, 2016). The Equality Act 2010 makes it illegal to discriminate against a person due to their HIV status (National AIDS Trust, 2016). Paramedics must maintain the patient's confidentiality, and ensure their interaction remains professional (Health and Care Professions Council, 2012). The exploration of LGBT health inequality with paramedic practice is long overdue.

Conclusion

The Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) was once considered a life-limiting condition where people would frequently develop severe opportunist infections with poor clinical outcome. The discovery of antiretroviral treatments quickly revolutionised HIV care, which are now available to patients living with HIV, with evidence to suggest these medications can effectively reduce the chance of HIV transmission as an additional preventative measure. People living with HIV can now expect a good quality of life, with a normal life expectancy if they comply with their bespoke HIV treatment. Unfortunately, HIV still remains a burden amongst MSM and transmission is rising within this community. It is therefore essential for ambulance staff and healthcare workers to make ‘every contact count’ by identifying high-risk behaviour; signposting patients to HIV testing services and engaging patients in safer sex conversation. This article provides a timely overview of HIV in an attempt to reduce the rate of transmission in the UK, and calls for paramedics to join the fight against HIV.