Health Education England (HEE) define quality care as ‘clinically effective, personal and safe, with patients treated with compassion, kindness, dignity and respect’ (HEE, 2016). A renewed National Health Service (NHS) focus on compassion in patient care followed the high profile shortcomings in care exposed by relatives of patients and investigated by the Francis Report into Mid Staffordshire NHS Trust (Bailey 2012, Francis 2013).

Whilst nursing dominated the consequent discourse around compassionate care with a set of values collectively called the 6 Cs (care, compassion, competence, communication, courage and commitment) (Cummings and Bennett, 2012), there have since been moves to embed the 6 Cs of nursing into paramedic practice (Nevins et al, 2016).

These are some of the factors which prompted an investigation into student paramedics' understanding of compassionate patient care and of the emotional labour involved in care giving. Paramedics are expected to respond quickly in unpredictable situations whilst maintaining personal resilience and being available to others in times of need. Like other first responders, they have little advance briefing of the nature of the emergency call and little time to prepare mentally before arrival.

Emotional labour is described as the work required when dealing with the public in face to face encounters, and extends to the private sphere when the worker processes such emotions (Williams, 2012).

Smith (2012) describes emotional labour as the sheer effort of work expended by nurses and student nurses in sustaining the traditional image of smiling nurses at all times, and particularly when their own emotions were supressed in order to maintain that image.

Compassion is described by Cummings (2012) as ‘intelligent kindness’ given by forming relationships with patients based upon empathy, respect and dignity. It relates to the manner in which care is given.

The study presented here aimed to selectively review literature on emotional labour and to utilise a small scale research project to open up a discussion on factors affecting emotional labour for student paramedics, and barriers they identified to delivering compassionate care. The objective was ‘to point, illustrate and comment’ (Hochschild, 2012 p12) on responses in order to direct future research.

Literature review

‘He can suppress his emotional response to his private problems, to his team mates when they make mistakes…and he can stop himself from laughing about matters which are identified as serious and stop himself taking seriously matters defined as humorous. In other words he can supress his spontaneous feelings in order to give the appearance of sticking to the effective line, the expressive status quo.’

Hochschild defines the term ‘emotional labour’ as ‘the management of feeling to create a publicly observable facial and bodily display’ (Hochschild, 2012). Where this exists as an integral part of one's professional role, she argues that ‘emotional labour is sold for a wage and therefore has exchange value’ (ibid).

Hochschild's study focused upon the role of flight attendants whose labour was observed to be vital both to the health and safety of airline travellers but also to the selling of a caring corporate brand image. The study showed that the airline company taught flight attendants to bury deeper feelings in order to manage their emotions when faced with difficult passengers or circumstances. The importance of smiling was described in her research as being both to hide fatigue and to make the work appear effortless. Amongst this overwhelmingly female workforce their smile was considered to be one of a worker's greatest assets and they were encouraged to ‘really lay it on’ (Hochschild, 2012).

Smith's seminal study and follow up (1992; 2012) discussed the emotional labour of health care as rendered invisible, and impacted by the pressures of health care targets with emphasis placed on ‘effectiveness, efficiency, outcomes and economics’ (Smith, 1992). Smith raised the dangers of care being lost in management systems. Oakley, cited in Smith (2012) revealed expectations by employers to show ‘alertness to the needs of others’ as both the mark of a good woman and a good nurse. Bone (2009) notes that within Western culture the binary position of ‘emotion / subjective’ relates to the female, whilst the ‘reason/objective’ relates to the male.

The theme of managed emotions continued in research into aggression in emergency departments highlighting occurrences of dangerous and unpredictable events and their impact upon staff (Ferns and Chojnacka, 2005; Ferns and Cork, 2008; Ferns and Meerabeau, 2009). The latter paper examined reporting by student nurses of receiving verbal abuse from patients and of feelings of sympathy toward aggressive patients.

More recently Riley and Weiss (2016) define emotional labour in a health care setting as ‘the act or skill involved in the caring role, in recognising the emotions of others and in managing our own’ (2016, p2).

Emotional labour, care and compassion are linked in the existing literature where the discourse has focused on traditionally female roles, (Hochschild, 2012, Smith, 1992, Hunter 2001 cited in Bone 2009, Bone 2009). With the exception of Williams (2012) who discussed nurse educator's awareness of the paramedic role in the teaching of paramedics in higher education, there remains a notable paucity in the literature of the experiences of paramedics. Williams noted the masculine culture dominant in paramedic practice and its influence upon student paramedics whom she believed were socialised to supress their emotions (Williams 2013a and 2013b).

In McCann et al (2013) participant observational study of paramedics within one ambulance service it was noted that respondents focused on the technical aspects of caring for patients as a tactic in coping with their emotions, and that by doing so they avoided becoming emotionally connected to the patient. A majority of respondents (76%) indicated they had not received sufficient training to cope with the emotional effects of incidents but instead relied upon a level of ‘street level professionalism’, interpreted as a ‘fall-back’ coping mechanism in the face of organisational targets, abusive patients and unpredictable environments. Here there are echoes of both Smith's warnings about care being lost in management targets and of Williams's concerns about paramedic culture education (Smith 2012, Williams 2012, 2013a).

The use of questionnaires in research by Fjeldheim et al (2014) on southern African paramedic trainees demonstrated that they had a high risk of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and speculated that trainee emergency care workers might be at higher risk since they were in unfamiliar environments, tended to be younger, lacking field experience and with added academic pressures. In another southern African study Minnie, Goodman and Wallis (2015), suggested that emergency medical workers ‘often suppress their emotions and feelings so as to live up to the image of being strong and resilient’. This resonates with the earlier study by Williams (2013a). Respondents identified that talking to colleagues was a key coping mechanism and acted as an informal de-briefing exercise. McCann et al (2013) also emphasised the importance of debriefing and in their research noticed the loss of ability to informally debrief due to time pressures as significant in how paramedics managed their emotions following distressing events.

The literature suggests a link between gender and age, and identifies strategies adopted in order to effectively manage emotions. This synergy of factors provided the framework for the research project.

Method

A self-administered survey was delivered by hand to a convenience sample of undergraduate paramedic students who provided responses to a three part survey. Two parts collected responses given on a five point Likert scale while one part comprised multiple choice questions where respondents could select as many answers as they thought relevant. Additional information was sought relating to demographic details specifically gender and age as these emerged as relevant in the literature review. The number of available respondents were 44 and the number of actual respondents were 32 (n=32). A pilot study had previously been undertaken to test and gain feedback on the clarity of the questions and the survey design and layout. The time taken to complete the survey was measured and found to be less than 15 minutes, which was considered reasonable. Microsoft Excel was used to facilitate statistical description and data was coded prior to analysis with a 1 showing a positive response and a 0 recorded for a negative response.

Limitations

The convenience sample had experienced two weeks in the practice environment in an observational role. This sample may therefore have given false positives given that the literature reviewed in chapter one specifically relates to youth and inexperience. Furthermore, previous experience in healthcare or other setting was not recorded. This may have had an impact upon student paramedic's responses since for some the placement period may not have been a first exposure to traumatic events. Since the literature recognises a range of occupations where emotional labour has been studied and students may have had already developed coping mechanisms.

Ethical considerations

Participant confidentiality and anonymity were maintained by having surveys returned into a centrally located pigeon hole. Consent was obtained from participants via consent form and ethical approval was provided by the university promoting the study.

Results

There were 32 respondents from the sample group, 11 male and 21 female. A breakdown by age is shown in table 1.

| Attribute | Number of respondents by gender | |

|---|---|---|

| Male (n=11) | Female (n=21) | |

| Being reassuring | 8 | 21 |

| Kindness | 10 | 17 |

| Listening | 7 | 17 |

| Showing respect | 8 | 16 |

| Empathising | 10 | 15 |

| Comforting | 9 | 15 |

| Making comfortable | 4 | 14 |

| Making patients feel safe | 8 | 13 |

| Acknowledging fears | 6 | 12 |

| Maintaining dignity | 8 | 8 |

| Having knowledge of the patient | 2 | 8 |

| Empowering patients | 5 | 5 |

| Emotional Intelligence | 4 | 5 |

| Desiring to promote positive outcomes | 3 | 5 |

| Being masterful of skills | 1 | 2 |

Two thirds of the males were evenly spread between the two youngest age groups. Of the females 61% were in the youngest category with a further 28% in the next youngest. All female respondents were aged less than 30 years.

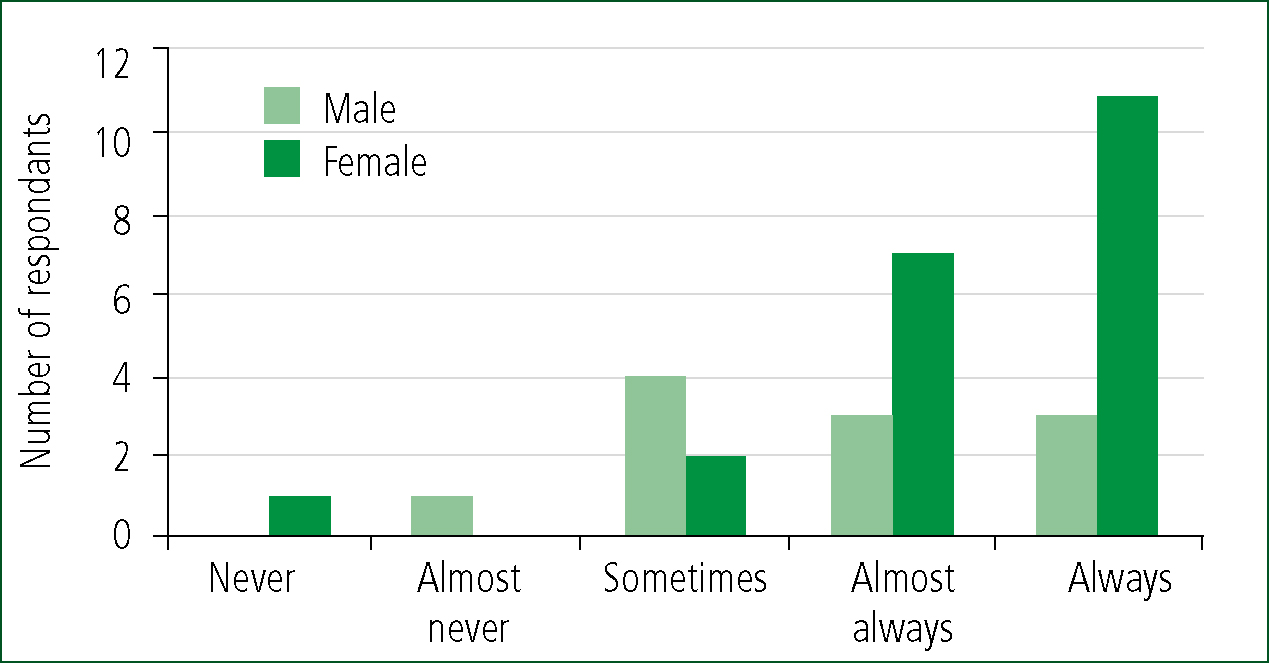

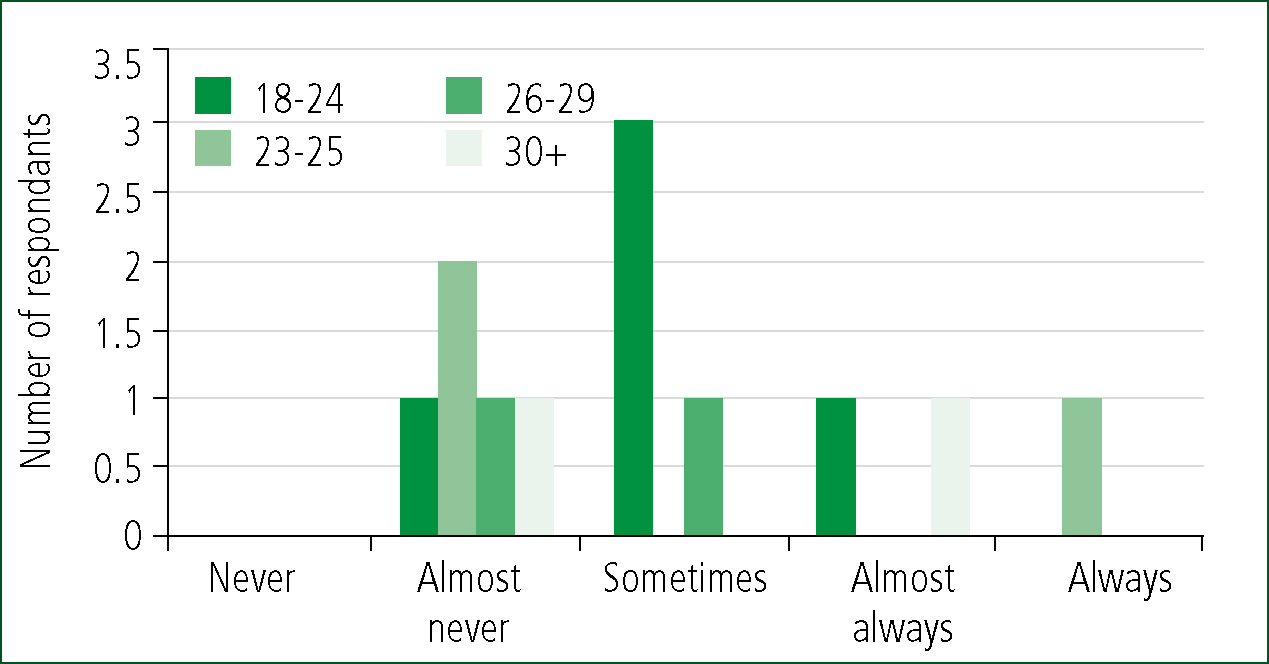

24 out of 32, or 74% of respondents were ‘always’ or ‘almost always’ aware of things that upset them whilst in placement. Of these 6 were male (approximately half the males) and 18 female (86% of females). Amongst the males responses were spread across the age ranges. Of the female respondents 61% were in the youngest category and 28% in the next youngest category.

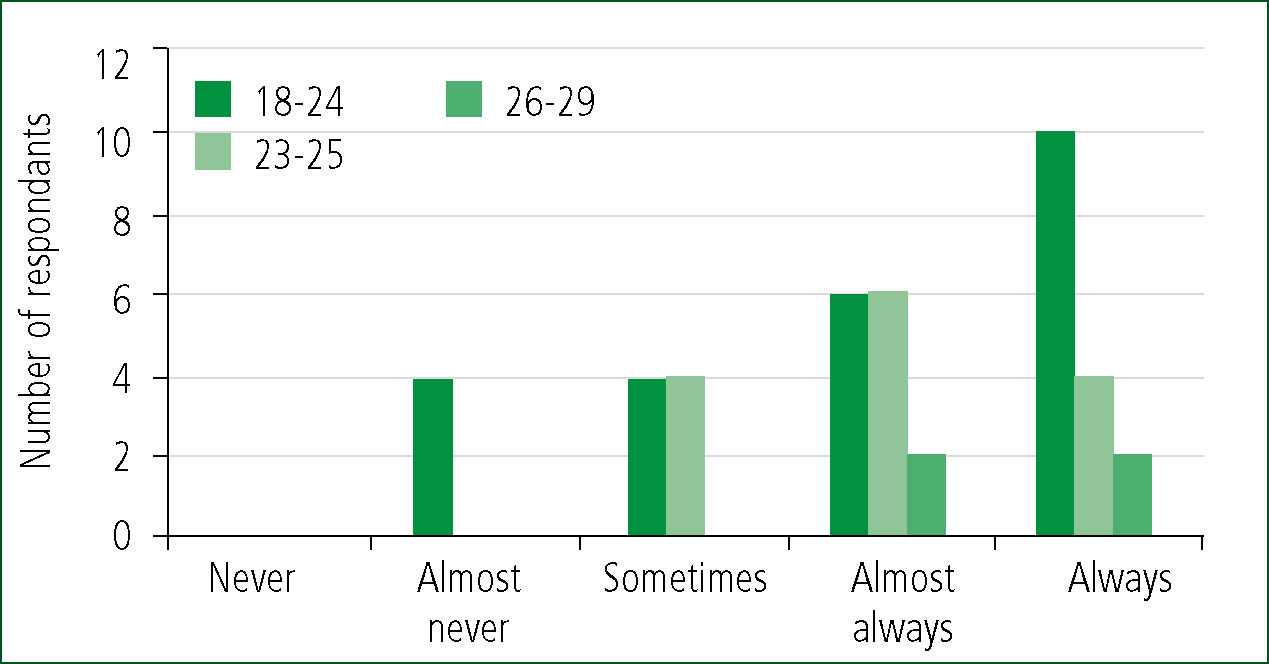

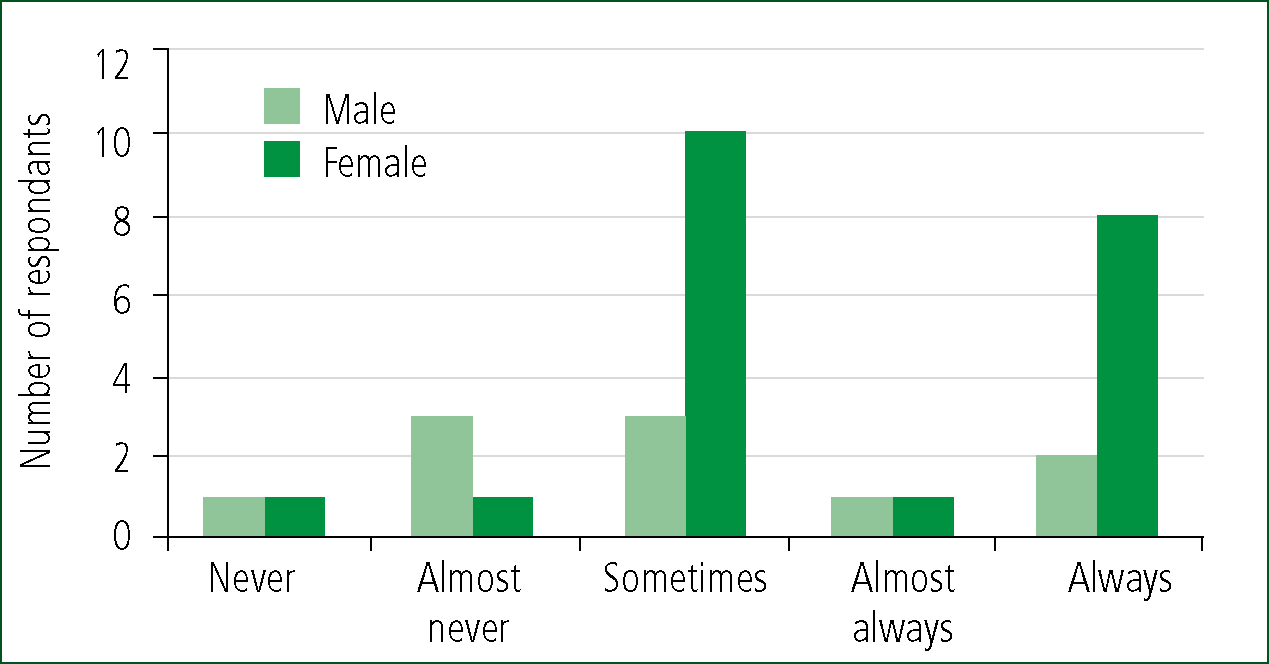

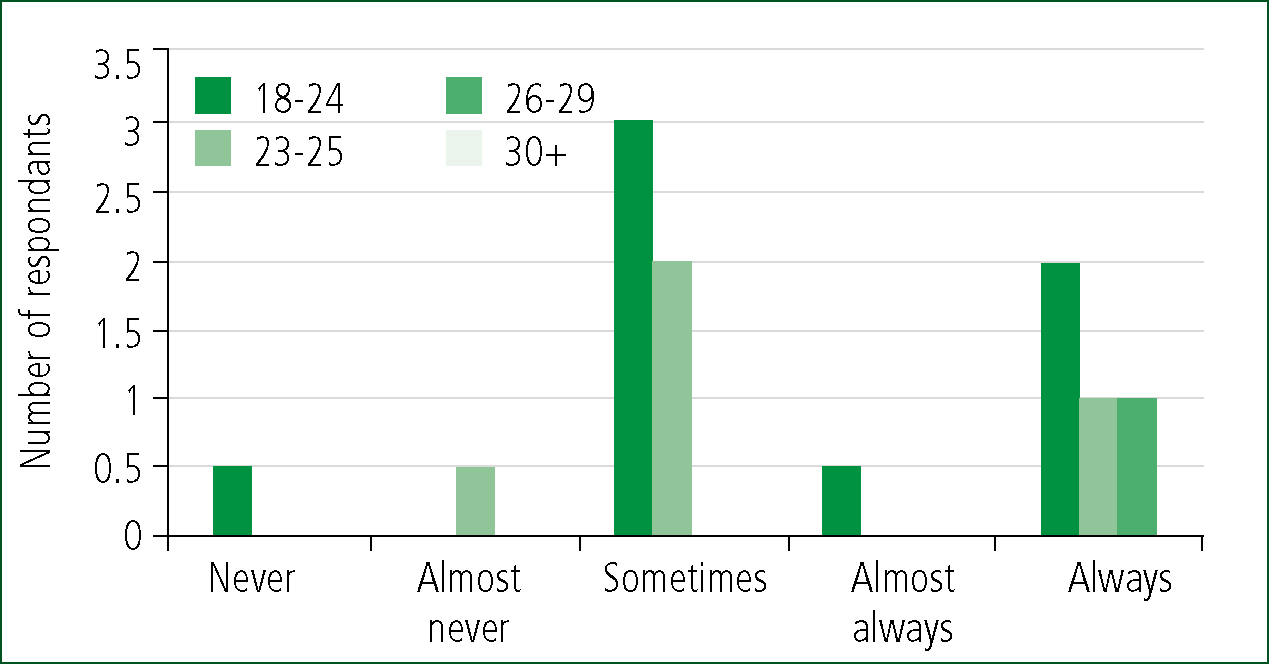

In response to the statement shown in Figure 3 18 out of 32 respondents returned ‘always’ or ‘almost always’. Of these only 3 were male and as before responses were spread across the age categories. Females returning ‘always’ or ‘almost always’ numbered 15 where approximately half were in the youngest age category (18 to 22 years) and approximately half were in the next youngest age category (23-25 years).

12 out of all 32 respondents (37%) returned ‘always’ or ‘almost always’ responses to the above statement. A further 13 indicated that they ‘sometimes’ did, which when combined with the previous figure revealed that 78% of all respondents were at times covering up actual feelings when in placement.

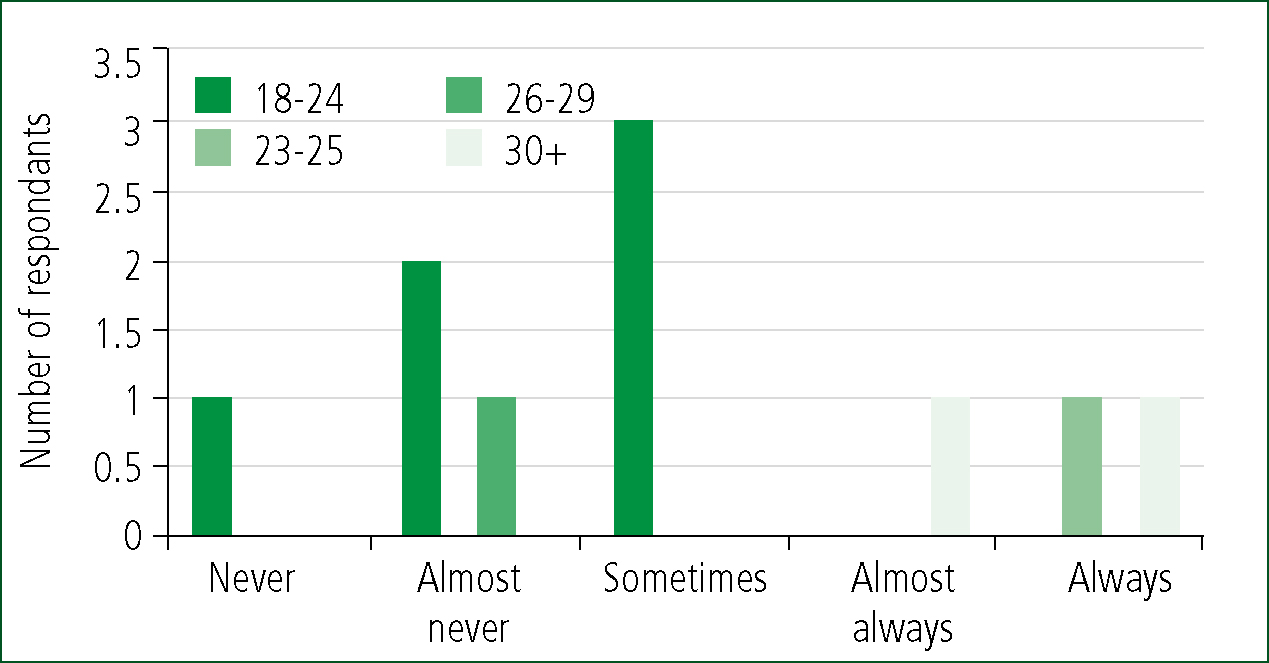

Gender and age analysis of this statement indicated in Figure 5 and 6 showed there was a concentration of males in the younger age category who were covering up, or burying feelings in placement. The literature identified that older respondents may be less likely to report characteristics of stress; however this small scale project indicates that even slightly older student paramedics may be concerned about revealing deep emotions in placement.

Females returned 19 responses where ‘sometimes’, ‘almost always’ or ‘always’ were selected in response to this statement. 58% of these were in the youngest age category (18 to 22 years). 86% of female respondents were covering up their emotions at some time.

Respondents were then asked to complete four multiple-choice questions. Questions 1 and 4 presented the same 15 possible answers but posed two different questions: ‘I understand compassion in my practice as…’ and, ‘Doing my job well involves…’. They were asked to circle as many attributes as they felt important to them in their delivery of compassionate care.

10 out of 11 male respondents returned a top two attributes for demonstrating their compassion as ‘kindness’ for and ‘empathising’ with patients. The top two for female respondents were ‘being reassuring’, with ‘listening’ matching ‘kindness’ as a top selection.

When asked to think of attributes which would illustrate how paramedic students may demonstrate ‘doing my job well’, there were six responses selected by almost all males. Despite ‘kindness’ and ‘empathising’ being more frequently selected when asked about demonstration of compassion, these were surpassed by ‘being masterful of skill’, ‘maintaining dignity’, ‘making patients feel safe’, ‘comforting’ and ‘showing respect’. Amongst female respondents ‘being reassuring’ remained one of the top two selected attributes, with ‘showing respect’ being slightly more popular.

Discussion

Key findings of the research can be summarised. The results showed that three quarters of the paramedic students in the sample were aware of being upset whilst in placement. This is a significant finding since it means that even after a short exposure to practice placement and in an observational capacity, these students were already aware of pressures of time, targets and task. This is much earlier in their careers than in the Williams (2013b) study where the smaller group of 8 participants had experience four periods of placement and were at the end of their second year of study. The results in this study appeared to demonstrate that 78% of student paramedics were indeed ‘covering up feelings’ whilst in placement resonating with Hochschild's (2012) interpretation of managed emotions within a professional role, despite not being employees. Gender and age analysis of responses to the corresponding statement showed there was a concentration of males in the younger age category who were covering up, or burying feelings in placement. 86% of female respondents had covered up emotions at some point in the short placement period the majority being in the younger age group.

| Attribute | Number of respondents by gender | |

|---|---|---|

| Male (n=11) | Female (n=21) | |

| Being reassuring | 10 | 20 |

| Kindness | 9 | 19 |

| Listening | 9 | 19 |

| Showing respect | 10 | 21 |

| Empathising | 8 | 17 |

| Comforting | 10 | 11 |

| Making comfortable | 8 | 14 |

| Making patients feel safe | 10 | 21 |

| Acknowledging fears | 7 | 17 |

| Maintaining dignity | 10 | 14 |

| Having knowledge of the patient | 8 | 14 |

| Empowering patients | 7 | 13 |

| Emotional Intelligence | 7 | 12 |

| Desiring to promote positive outcomes | 8 | 12 |

| Being masterful of skills | 10 | 17 |

It is noteworthy that younger students comprised 56% of the sample size (age 18 to 22 years) where 45% of males and 62% of females fell into this category. The results appeared to support Fjeldheim et al (2014) in their assertion that younger emergency workers were at risk of adverse stress effects although there is no evidence in my research to link the covering of emotions to adverse stress effects. The research does show however that regarding both male and female students, there is a high level of awareness of their emotions in placement as well as an early understanding of an unspoken need to cover them up. This may align with Williams (2013a) analysis of masculine culture within paramedic practice, and the need to ‘get on with the job’ or ‘deal with it’ (Williams 2013b, p514).

Analysis of respondents who discussed things that upset them with their practice educator showed that female students ‘always’ or ‘almost always’ did 15 times out of 21 compared to only 3 male students (out of 11). This implied that more young women than men discussed with their practice educators things that upset them. If 9 of these female students were ‘always’ or ‘almost always’ covering up their emotions then more research would be required to illuminate the nature of these discussions. It is notable that 25% of respondents only ‘sometimes’ spoke to their practice educators when feeling upset in placement and 15% ‘almost never’ discussed their upset feelings. This finding alone suggests a need for further research.

In terms of responses which may have demonstrated understanding of attributes required for student's delivery of ‘compassion in my practice’ and of ‘doing my job well’, there were differences noted between responses to the two statements posed. Both male and female students identified softer skills as necessary for demonstrating compassion but ‘being masterful of skills’ leapt in importance when students were asked to consider what attributes demonstrated ‘doing my job well.’ McCann et al (2013) found that participants in their study focused on the technical aspects of caring for patients as a tactic in coping with their emotions.

| Perceived barrier | Number of all responses |

|---|---|

| Focusing on the technical elements of patient care | 17 |

| Expectation to get on with the job | 12 |

| Finding time to deal effectively with patients | 12 |

| Use of surface emotions to mask true / deep feelings | 9 |

| Being off late at end of shift | 9 |

| Where the crew has focussed solely on the task | 7 |

| Working with different people each shift | 6 |

| Low number of life-threatening calls you attended | 6 |

| High number of life-threatening calls you attended | 2 |

Students in the sample appeared to identify the ‘focus on technical skills’ as a barrier to compassion and did so whilst seeming to maintain a disconnection between skills mastery and compassionate practice. This raises an interesting question regarding the extent to which paramedic students saw being masterful of skills as an important functional rather than compassionate expression.

Other popular responses in this section of the survey appear to demonstrate an early awareness by student paramedics of pressure to get on with the job and of finding time to adequately demonstrate compassionate care. This is shown in the joint second and third most popular response to ‘barriers you have seen or felt to compassion’ as ‘finding time to deal effectively with patients’ and ‘expectation to get on with the job.’ For Benner (cited in Hunter and Deery, 2009) knowing the patient is the key to delivering effective care while McCourt and Stevens (2009) discuss continuity of the midwife/client relationship as an important theme in in the delivery of patient centred care. Paramedic intervention on the other hand limits relationships between practitioner and patient to swift assessment, limited management followed by transfer or referral to another facility. Yet student paramedics after even a short placement may have already begun to recognise pressures of health care targets, as identified earlier by Smith (2012) as a barrier to compassionate care.

Conclusion and recommendations

This study focused on student paramedics' understanding of the emotional demands of paramedic practice in the delivery of compassionate patient care. It used a survey to investigate emotional engagement and self-awareness of student paramedics in placement, along with their impression of barriers to delivering compassion care. It has drawn upon the literature from studies of emotional labour and of compassion in care delivery and to link them with responses from students in this study.

The small scale of the research was in keeping with previous research undertaken with paramedic students, yet indicates the need for larger scale data collection. Consideration should also be given to future longitudinal cohort studies.

The results are important to paramedic educators, particularly for placement educators regarding the ranges in awareness amongst the student body of the emotional demand of their future role. In future a greater understanding of students needs will enable new ways to integrate the 6 Cs of nursing into the paramedic curriculum.