In 2012, intravenous (IV) paracetamol was introduced to the range of analgesics available to paramedics. The Association of Ambulance Chief Executives (AACE) stated that IV paracetamol is effective at reducing opioid requirements and can be used for patients in severe pain as part of a balanced pain regime (AACE, 2013: 337). The AACE also state that IV paracetamol should be considered in the presence of musculoskeletal pain or when morphine is contraindicated (AACE, 2013: 8). IV paracetamol also has a greater safety profile, with side effects such as hypotension being extremely rare, whereas morphine has a far greater range of side effects including respiratory depression, nausea and vomiting (AACE, 2013). These side effects could cause detriment to the patient experience and must be taken into account when deciding on a pain regime. Therefore, adverse reactions and their incidences of occurrence have been included within this review.

The purpose of this review is to investigate the research between these two analgesics and their efficacy as analgesics.

A clinical question was constructed in order to compare previous research studies: ‘Is IV paracetamol/acetaminophen as effective an analgesic as IV morphine for patients in non-cardiac pain?’ This was inputted into relevant article search engines. The results were then considered, and using inclusion and exclusion criteria, they were systematically sorted through, critically analysed and their results interpreted.

Search process

The literature search, along with a Cochrane Database search was conducted on 3 April 2015. This question in its key terms was inputted into PubMed, the British Medical Journal (BMJ), University of Birmingham library and NHS Evidence research databases to produce five articles that were reviewed, after relevant exclusions were made (see Appendix 1 and 2). The reason these databases were used was to gain as large a database of research as possible, including journals that specialised in pre-hospital and emergency department care, such as the Emergency Medicine Journal via the BMJ.

Background

Pain can be described as ‘an unpleasant, subjective, sensory and emotional experience, associated with actual or potential tissue damage’ (International Association for the Study of Pain, 2012). With between 50–70% of patients calling 999 due to pain, it forms a large part of the paramedic's scope of practice (Lord, 2009). A qualitative study found that patients in pain receive poor care in the pre-hospital setting due to inadequate analgesia (Iqbal et al, 2012). This review will help form part of a paramedic's scope for their evidence-based practice and hopefully improve pre-hospital care for patients in pain.

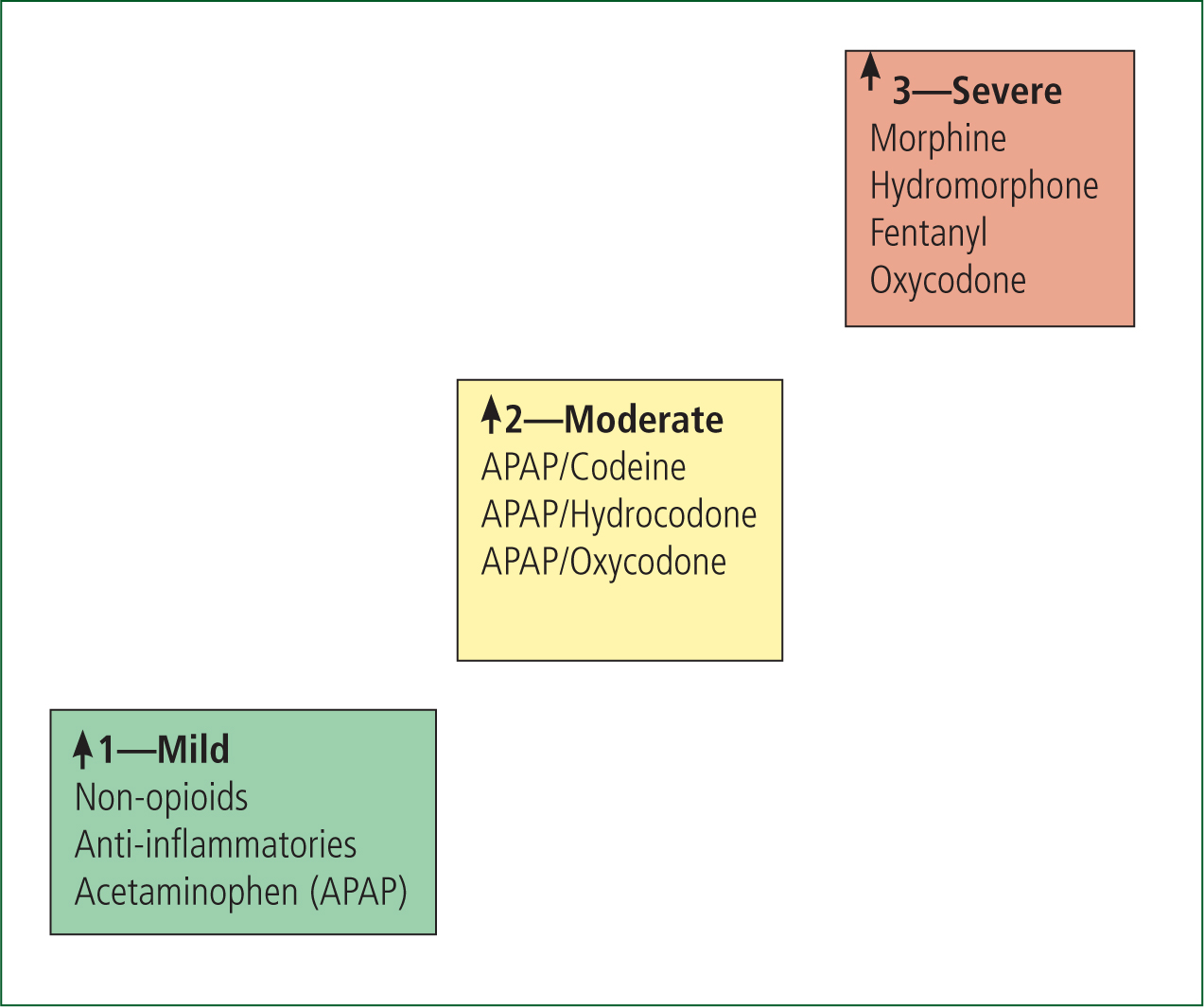

Paramedics in the UK currently use morphine for managing severe pain, as this used to be the only analgesic available as part of the ‘pain ladder’ (AACE, 2013: 8). The pain ladder starts with paracetamol and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatories for slight pain at stage 1; weak opioids, such as tramadol or oxycodone, for moderate pain at stage 2; and strong opioids, such as morphine, for severe pain at stage 3 (see Figure 1) (BMJ Clinical Evidence, 2014). This is slightly adapted for paramedic practice, starting with non-pharmacological interventions such as positioning, cooling or splinting and moves into the pharmacological route if these initial interventions fail (AACE, 2013: 7). The choice of analgesic medications for a paramedic includes: entonox, ibuprofen, morphine (oral or IV or IM) and paracetamol (oral or IV), and the analgesic used is the clinical decision of the practitioner (AACE, 2013: 7).

This review will not include pain of a cardiac nature, such as myocardial infarction, as IV morphine is stated as the best medication for these patients for its analgesic effect and reduction of pre-load on the heart (Waller et al, 2010; AACE, 2013). Additionally, there will be no discussion surrounding the anti-pyretic effect of IV paracetamol and its possible implications for patients in pain secondary to sepsis.

Critical appraisal of evidence

As part of the critical appraisal, each piece of research was subject to a critical appraisal tool relevant to the type of study (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2013). Based on the hierarchy of evidence relevant to the research question, randomised control trials were to be reviewed first, as they are considered the ‘gold standard’ of research study (Pearson et al, 2007).

Studies comparing paracetamol versus morphine

The first of these studies (Craig et al, 2012) was a randomised double blind pilot study comparing IV paracetamol against IV morphine in 55 patients suffering from acute limb trauma in the emergency department. The patients were either given 1 g paracetamol IV or 10 mg morphine IV; the patient's pain score was then measured on a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and incidence of adverse reactions recorded. The VAS is a 100 mm line where the patient marks their pain score on the line, one end being ‘no pain’ the other being ‘the worst pain’, and is vertical to reduce left to right bias (Parahoo, 2006: 296). The mark was then measured, allowing the researcher to gain a very sensitive form of data collection. This form of data collection increases the validity of the study when compared to studies using the numerical rating score (NRS) and is able to note subtle changes in the patient experience (Parahoo, 2006: 296). The VAS is important for this review as nearly all the research studies use it as a way of measuring a patient's pain. Each study measures a patient's pain after 30 minutes, allowing for the results to carry a sound validity and reliability when compared together (Polit and Beck, 2006).

A change of 13 mm or more on the VAS has been deemed to be clinically significant when measuring a patient's pain score (Todd et al, 1996). This was inputted into the two group, two sided t-test, determining that the study only requires 21 patients in each group (Craig et al, 2012).

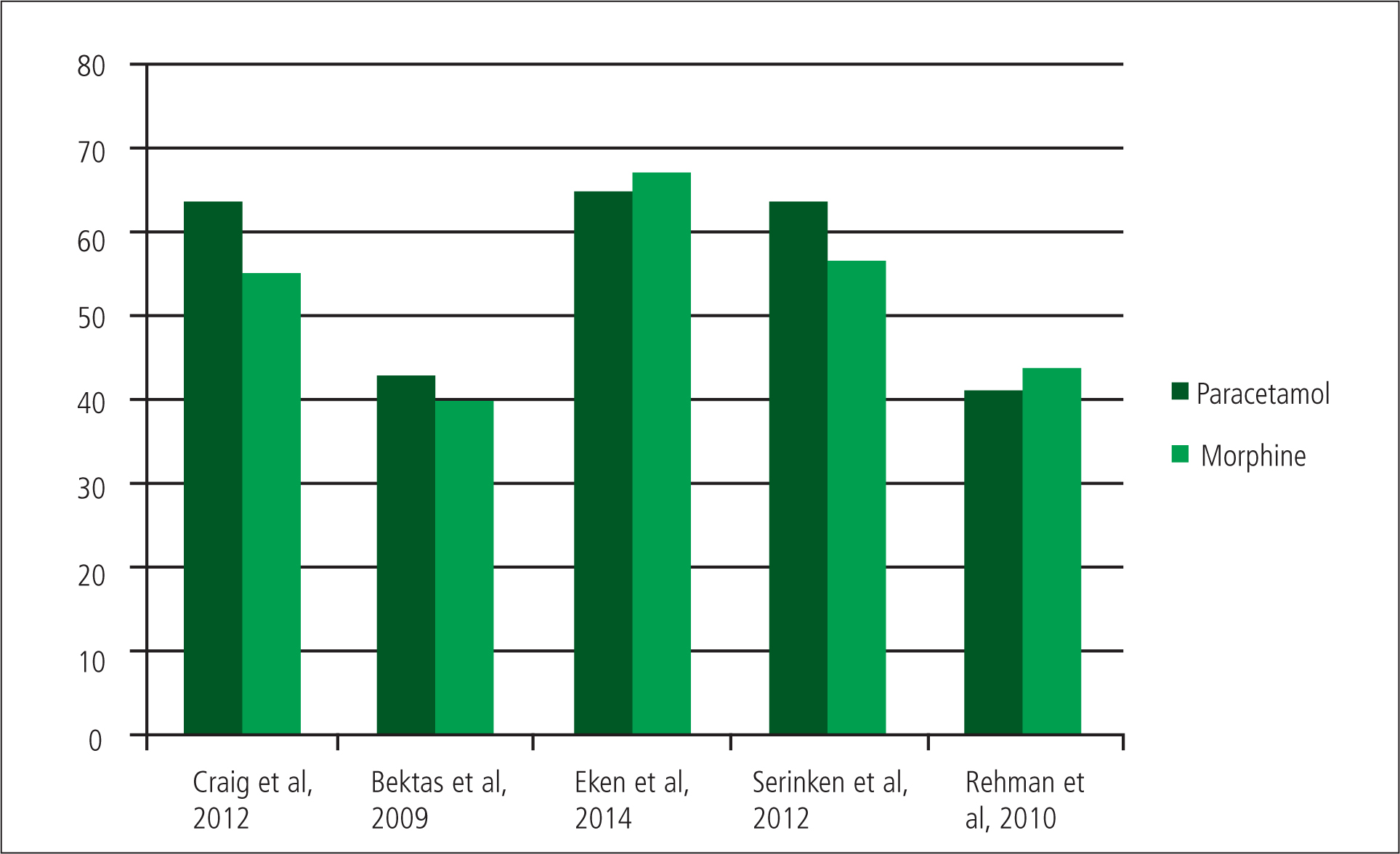

The results of the trial by Craig et al can be shown to be statistically significant, as they had 27 patients in the paracetamol group and 28 in the morphine group. This gives the study a strong statistical conclusion validity (Polit and Beck, 2006). As a caveat, the sample is from a single-centre study and could be exposed to sampling bias. This is reflected in the conclusion by Craig et al that paracetamol is ‘comparable’ to morphine. However, the results show that paracetamol appears to have lowered the mean pain scores at every time interval more effectively than morphine, between 6.3 mm to 10 mm (Craig et al, 2012). At 30 minutes the mean reduction in the VAS of the paracetamol group was 63.5 mm and 55 mm for the morphine group.

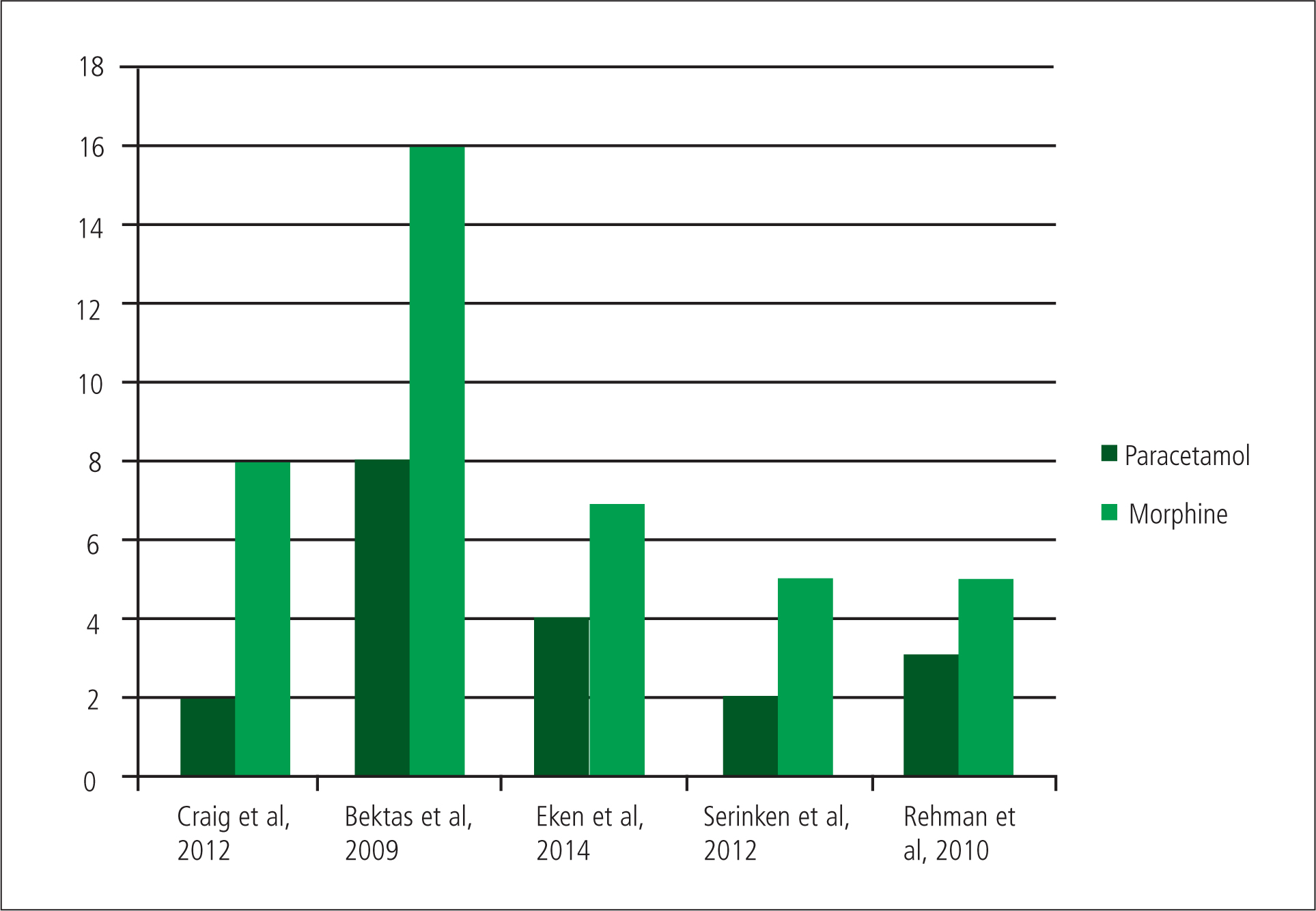

The incidences of adverse reactions were recorded as nausea, vomiting, hypotension, respiratory depression and itching, which are synonymous with other trials allowing comparison across others.

Craig et al observed eight adverse reactions in the morphine group and two in the paracetamol group, showing that in this study morphine does have a higher incidence of adverse reactions than paracetamol (Craig et al, 2012). There is a possible explanation for both the VAS score and adverse reactions for the morphine arm of the study. Because of the lack of titration in the study, any patient over 50 kg would have received 10 mg IV morphine as a rapid bolus, increasing the likelihood of adverse reactions, especially in lighter patients (Waller et al, 2010: 269). There may have also been a reduction in analgesic effect in heavier patients who may have required a higher dose if morphine were titrated to their weight. This does present IV paracetamol as a more effective analgesic to IV morphine and may cause less adverse reactions.

In 2009, Bektas et al investigated the efficacy of morphine against paracetamol in the treatment of pain secondary to renal colic. They investigated the two medications in a randomised placebo-controlled trial in Turkey.

The team recruited 146 patients presenting with suspected renal colic in a single centre study. After relevant exclusions, patients were randomised and given either 1 g paracetamol IV or 0.1 mg/kg morphine IV or normal saline solution.

Bektas et al found that paracetamol reduces the VAS score at 30 minutes more effectively than morphine and with a smaller confidence interval, 43 mm (95% CI, 35–51 mm) by comparison to 40 mm (95% CI, 29–52 mm) for morphine and a 27 mm drop in the VAS (95% CI, 19–34 mm) in the placebo group (Bektas et al, 2009).

Adverse reactions were defined the same as previous studies, occurring at least once in 8 patients of the placebo arm, 11 in the paracetamol arm and 16 in the morphine arm of the study. However, as most of the adverse reactions were nausea and vomiting, and renal colic can cause nausea and vomiting, it is difficult to determine whether the illness or intervention caused this (Porth and Matfin, 2011; Waller et al, 2010). If these reactions are removed the results show that eight patients given paracetamol had an adverse reaction, compared to 16 for morphine and seven for placebo. This suggests that IV paracetamol has a better safety profile than IV morphine.

It would appear paracetamol proves to be a better pain relief even when morphine is titrated to a patient's weight.

By using a placebo-controlled study the validity increases, as this allows the researchers to more properly attribute the results to the conclusions (Parahoo, 2006). The study has stated that it received full ethical approval from local and central governments; however, it would be difficult to use this methodology to replicate in the UK on ethical grounds in using a placebo as an analgesic (Polit and Beck, 2006).

Even though the sample size was large enough to produce clinically significant results, there were 11 patients excluded during the study due to protocol violations, including patients who required rescue analgesia within 30 minutes. The patients were only given rescue analgesia if deemed to be in too much pain by an observer. As pain is a subjective experience for each person, patients may have been withdrawn because of the researchers or their own perceptions of pain, rather than the patient's own experience. Withdrawal data is not included, reducing the validity of the study, as the final sample could have been bias (Polit and Beck, 2006). Furthermore, the age range was 18–55 years, making it difficult to generalise the findings to older patients.

Finally, Bektas et al (2009) were unable to fully describe the mean dose prescribed for the IV morphine group, as it was based on patients' weight and this data is not given. Additionally, the researchers did not weigh the patients, simply asking the patients for their own estimation. This has been acknowledged by the researchers as a flaw; however, it renders results of the morphine group almost unusable, as the patients could have generally underestimated, causing them to receive less analgesia and subsequently cause a less significant reduction in pain score. Alternatively, the patients could have overestimated, resulting in a higher dose of morphine and an increase incidence of adverse reactions; however, this does not appear to have occurred upon reflection of the results. Ultimately, IV paracetamol can be shown to be a more effective analgesic with a lower incidence of adverse reactions. Nevertheless, due to the lack of data regarding morphine doses, this must be taken with caution.

Eken et al (2014) compared paracetamol, morphine and dexketoprofen for patients with acute lower back pain. The study, conducted in Turkey, as a single-centre randomised double-blind control trial, selected 137 patients of 46 in the paracetamol group who received 1 g IV and 45 in the morphine group, who received 0.1 mg/kg IV (Eken et al, 2014). The methodology is similar to the study by Bektas et al (2009), although in this case without a placebo group. This is understandable, as Eken was a researcher in the study by Bektas et al. This would have helped Eken in the planning of the study, as previous problems and issues that arose in the Bektas et al (2009) study could be used to form a better research model.

On the other hand, this also introduces the possibility of researcher bias within the study, where the researcher wishes this new study to agree with the results of their previous study, thereby causing the study to have the possibility of prejudiced results caused by the researcher and reducing its external validity (Polit and Beck, 2006). The paper does state that there were no conflicts of interest within the study; however, this is worthy of note.

Within the study, morphine reduced the mean pain score after 30 minutes by 67 mm (CI 95%, 58–72 mm) against 65 mm (CI 95%, 60–73mm) for paracetamol (Eken et al, 2014). This showed that morphine is no better an analgesic than paracetamol. Eken et al (2014) found that four patients in the paracetamol group suffered from adverse reactions, as compared to seven for the patients who were given morphine.

‘As shown, IV paracetamol is as effective an analgesic as morphine. Furthermore, it may induce no more, to fewer, side effects than morphine and removes the need for pre-emptive metoclopramide’

Unfortunately these findings are difficult to generalise, as the researchers did not use the titration method when conducting the study and based the morphine dose on ‘patient statements’ regarding their pain. There is also no inclusion of the average dose of morphine given, which could have been different to the trials by Craig et al (2012) and Bektas et al (2009). On the other hand, it does make the study extremely relevant to paramedic practice, as the dose of morphine is titrated based upon the patient's experience and clinical observations and not on their weight (AACE, 2013: 321). This begins to highlight a trend that IV morphine is no more effective than IV paracetamol, and may cause more adverse reactions.

A study by Serinken et al (2012) involved 73 patients and concluded that IV paracetamol was as effective at treating renal colic pain as morphine. The study demonstrated a greater mean reduction of VAS scores at 30 minutes in the paracetamol group, 63.7 mm to 56.6 mm in the porphine group. There were also more adverse reactions in the morphine group: five compared to two for paracetamol. Unfortunately the sample sizes were bias in numbers and randomisation (paracetamol 38 and morphine 35). There is no description of how they were randomised and secondly how an initial 133 eligible patients for the study dropped to 73 (Serinken et al, 2012). This causes the study to have sampling bias, where a group is under or over represented systemically due to certain characteristics of the group (Polit and Beck, 2006). This is because without detailing the randomisation process and appearing to ‘cherry pick’ the right patients for the study, the researchers cannot clearly show that they did not include or exclude certain patient groups from the trial in order to make their results have greater significance (Jadad, 1998). This causes the study to lack validity, as it is not able to properly identify the outcome it was designed to measure, and this will reduce the strength of the conclusions of the study (Polit and Beck, 2006).

Furthermore, Eken was also part of this research study along with others from previous studies, therefore questioning if these results occurred due to the intervention or possible manipulation by the contributors.

A study conducted in Saudi Arabia in 2010 used a similar randomised placebo-controlled methodology for patients entering the ED with acute painful sickle cell crisis (Rehmani, 2010). 106 participants were randomised to have 54 in the morphine group and 52 in the paracetamol group. However, the randomisation is not detailed and is unable to account for why the groups are not balanced. Rehmani (2010) also appears to remove the entire placebo group from the study with no mention of the group even being selected, therefore questioning why the study claims to be a placebo-controlled trial. This reduces the validity of the entire study, as to drop a whole arm of a study questions whether or not it has been conducted correctly.

The patients in the trial were given either 1 g IV paracetamol or 0.1 mg/kg IV morphine. Pain scores were measured on a VAS at 30 minutes and adverse reactions, similar to that of the study by Craig et al, were recorded. Rehmani (2010) found that morphine reduced the patient's VAS by 44 mm (95% CI, 33–56 mm) with five adverse reactions, and paracetamol by 41 mm (95% CI, 32–49 mm) with three adverse reactions. He concluded that IV paracetamol is an efficacious and safe treatment for patients in painful sick cell crisis (Rehmani, 2010). This supports previous research suggesting paracetamol is as effective as morphine, although the incidences of adverse reactions are similar.

Paracetamol versus morphine

The clinical question asks whether paracetamol is as efficient as morphine at providing analgesia for patients in pain. The literature does not cover all different aspects of pain, although there is a wide variety analysed, including chronic pain, abdominal pain and pain from trauma. Therefore the findings from this literature review can be reasonably generalised to all patients in pain, as long as it is severe and not of cardiac origin.

The literature suggests that IV paracetamol is as effective as morphine at providing analgesia to a variety of conditions. There is also a general reduced incidence of adverse reactions for IV paracetamol than IV morphine. As a caveat, if proper titration had been detailed this may not have occurred.

Further research needs to be conducted with improved methodologies in order to establish fully if IV paracetamol is as effective than IV morphine with a greater safety profile.

Recommendations for practice

As shown, IV paracetamol is as effective an analgesic as morphine. Furthermore, it may induce no more, to fewer, side effects than morphine and removes the need for pre-emptive metoclopramide. Therefore if a clinician is presented with a choice between IV paracetamol and IV morphine, they should use their own clinical judgement, taking into account the safety profile of the two medication as well as their analgesic effects.

When choosing IV morphine, the clinician must ensure that it is titrated and not given as a large bolus, to reduce adverse reactions. As there is no guidance as to how to titrate, this review recommends the dose should be titrated 0.1 mg/kg to patient's weight.

There is a possibility that the conclusion IV paracetamol is as effective as IV morphine may be met with some resistance from ambulance services and emergency departments, as the cost of 10 mg of morphine is £0.19 and for 1 g/100 ml of IV paracetamol is £1.59 (Craig et al, 2012). This means potentially eight patients could be treated for pain with morphine for the price of one with IV paracetamol. This cost is offset by the price of the controlled drug cupboards, policy and procedure, as controlled drugs require having their own locked room with their own safes, separate from other medicines (AACE 2013). Once this has all been taken into account, it may be that the cost of IV paracetamol is synonymous with IV morphine.

Conclusions

Current studies directly comparing morphine and paracetamol have some flaws regarding blinding, randomisation and the use of previous researchers in similar studies. Some of the studies directly compared paracetamol and morphine, finding paracetamol to be as effective as IV morphine with less adverse reactions. However, these studies cannot be directly compared as all used a different system to titrate the dose of morphine. If a universal dosing regime was introduced, such as 0.1 mg/kg, future research and retrospective studies will be more comparable. Conversely, this allows the researchers to show that IV paracetamol is as effective as IV morphine in any kind of dose regime.

Due to the lack of validity of some of the studies, the conclusion can only be that IV paracetamol is as effective as IV morphine for the kinds of pain studied.

Currently, there is no data to recommend that IV paracetamol should be given before IV morphine. None of the studies appear to recommend IV morphine over IV paracetamol.

Placing IV paracetamol at the third stage of the pain ladder, more research is required in order to ascertain if IV paracetamol is as effective or more effective than IV morphine and has a better safety profile.