Paramedics are increasingly becoming involved in end-of-life (EoL) care. Despite approximately 33% of paramedics seeing a terminally ill patient at least once a shift (Munday et al, 2011), they can represent a significant challenge (Mengual et al, 2007). Professional guidance for paramedics exists from the Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee (JRCALC, 2016), yet every decision concerning resuscitation must be made after careful assessment of each patient's situation and such decisions never dictated by ‘blanket’ policies (Resuscitation Council UK, 2016).

Existing evidence base

A systematic review of published literature was performed in November 2016, using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses convention (Moher et al, 2009). Similar searches were performed of the ‘CINHAL PLUS with Full Text’ database, and two professional journals in the UK which target the paramedic profession, namely the Journal of Paramedic Practice and the British Paramedic Journal.

Qualitative research involving paramedics and their involvement in EoL care has already been conducted (Gakhal et al, 2011; Taghavi et al, 2011; Waldrop et al, 2014), but much of this relates to a broader discussion on palliative care, rather than the specific issue of do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation (DNACPR) orders. A recurring theme within a number of published research projects concerned an educational analysis for paramedics, particularly pre-registration programmes (Gakhal et al, 2011; Munday et al, 2011; Lamba et al, 2013), while other research did not specifically relate to paramedics, and included nurses and other clinical grades (Grudzen et al, 2009; Norton et al, 2012; O'Hanlon et al, 2013; Boot and Wilson, 2014; Freeman et al, 2015; Kazmierski and King, 2015; Mockford et al, 2015).

Research focused on an international dimension or which was not specifically UK-centred was found (Naess, 2009; Wiese et al, 2012); as was research which identified why paramedic involvement is sought at the EoL where a DNACPR is in place (Everhart and Pearlman, 1990; Ingleton et al, 2009; Gadoud and Johnson, 2011; Pettifer and Bronnert, 2013).

Literature has been published focusing on patient experiences at the EoL (ComRes, 2014), but no attitudinal studies have been published relating to paramedics in the UK with specific reference to DNACPR orders in the pre-hospital setting.

Research question

The current research question pertains to: ‘Paramedic attitudes towards do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation (DNACPR) orders in the pre-hospital setting’. The gap in published literature represented the primary driver for undertaking the research; the secondary drivers were its relevance to contemporary paramedic practice and the researcher's own personal interest in this field of pre-hospital enquiry. The research concentrated specifically on DNACPR orders and not the more generic topic of palliative care; the research question was intended to identify paramedic attitudes towards DNACPR orders only, and determine if any common themes were present in the data. Another important distinction is that the research focused exclusively on the pre-hospital setting, as this is where paramedics operate with a greater amount of autonomy and are required to make clinical decisions quickly, and often under pressure.

The challenge was to ensure that the research question was neither too narrow (thus blocking new discoveries), nor too broad (providing no parameters for designing or implementing research) (Flick, 2004).

Research method

Another key consideration for the researcher, who was the lead author, was to ensure methodological congruence (Morse and Richards, 2012), in that the purpose of the research, the research question, and method of research were all interconnected and did not become isolated, fragmented parts. The design, therefore, was a mixed-methods enquiry incorporating both quantitative and qualitative techniques, with the researcher adopting an interpretivist approach.

Also referred to as ‘social constructivism’ (Creswell, 2013), interpretivism permits the researcher to capture a complexity of views, as opposed to narrow meanings, and places a reliance on the participants' view of the phenomenon in question (Mertens, 2010; Denzin and Lincoln, 2011). The priority for the researcher was not to develop a theory, as if using a grounded theory approach (Hildenbrand, 2004; Bowling, 2009), but rather to identify a pattern of meaning from the responses (Mertens, 2010). The theoretical framework which lends itself to an interpretivist perspective is a qualitative one (Ulin et al, 2005). With an emphasis on exploration and explanation, rather than description, the qualitative design best supported the research as it helped to uncover unfamiliar or insufficiently researched subject matter, and was more effective than a quantitative approach in understanding the behavioural and attitudinal phenomena (Bryman and Burgess, 1994; Sanders and Wilkins, 2010). All respondents made use of the free-type boxes to articulate their individual perspectives on do not attempt resuscitation (DNAR) orders.

Sample

Paramedic-grade clinicians from two designated ambulance stations of a large NHS ambulance service located in the north of England were invited to participate in the research project (n=33), out of a total population of 56 operational staff from the two stations. Both ambulance stations are based in heavily-populated urban areas, although more rural areas are also served by the resources stationed there. Consent for participation in the research was implied on completion of the questionnaire. Relevant measures were taken by the researcher to ensure the availability of appropriate support for those paramedics who may have become distressed at being asked to complete the questionnaire. The voluntary nature of the research, as well as participant anonymity, was assured.

Distribution of the questionnaire

Ethical approval was sought and obtained from the NHS and the authors' academic institution at the beginning of March 2017. The questionnaires, and accompanying correspondence, were then distributed to the paramedics selected for the research project with their payslips for March. Participants were invited to return the completed questionnaires within 2 weeks.

Data analysis

In choosing a method of data analysis, the author has acknowledged the complexity of the existing health-care system, as well as the existence of multiple perspectives on the use of DNACPRs in EoL care. The imperative, therefore, was to identify a method of data analysis which accommodated these dynamics into the research (Gale et al, 2013). In addition to these considerations, the approach adopted to review qualitative and quantitative evidence had to be contingent on the aim of the review, and the nature of available evidence (Mays et al, 2005).

The researcher has chosen to adopt a form of thematic analysis developed by Ritchie and Spencer (1994). This framework method can be adapted to research that has specific questions, a limited time frame, a pre-designed sample and a priori issues (Srivastava and Thomson, 2009)—and as such, fits well with the parameters of this study. It is a well-established framework and is recognised as a robust analysis tool for qualitative data (Ritchie and Lewis, 2003; Elkington et al, 2004; Rashidian et al, 2008; Ayatollahi et al, 2010; Ellis et al, 2012; Heath et al, 2012; Sheard et al, 2012; Gale and Sultan, 2013). The researcher has been mindful of the potential risks of this framework analysis, in that it can suppress interpretive creativity and potentially reduce the ‘vividness of insight’ (Dixon-Woods, 2011) afforded by the respondents. On reflection, however, it is being accommodated into the research design to ‘… aid informed judgement, not mechanistic rule-following’ (Spencer et al, 2003:4).

The questionnaire comprised a total of 10 questions, and all responses were transcribed. Dominant themes were identified and response exemplars included to support the thematic analysis. Similarities between the themes were also identified and any patterns associated with the responses noted.

Results

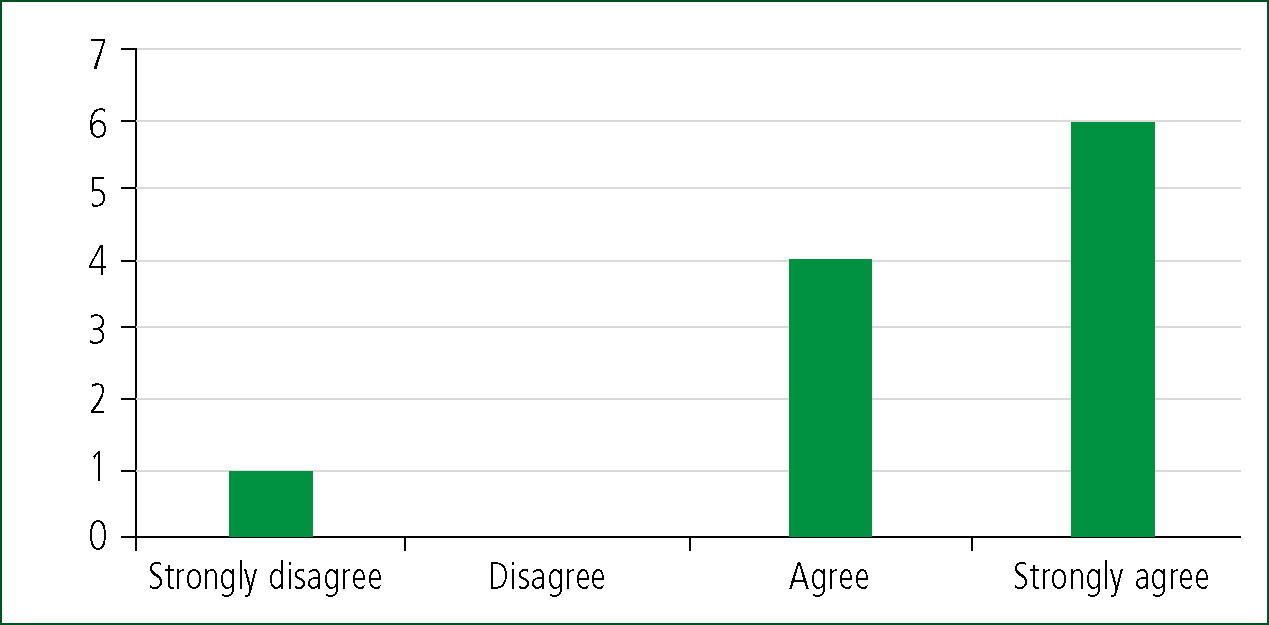

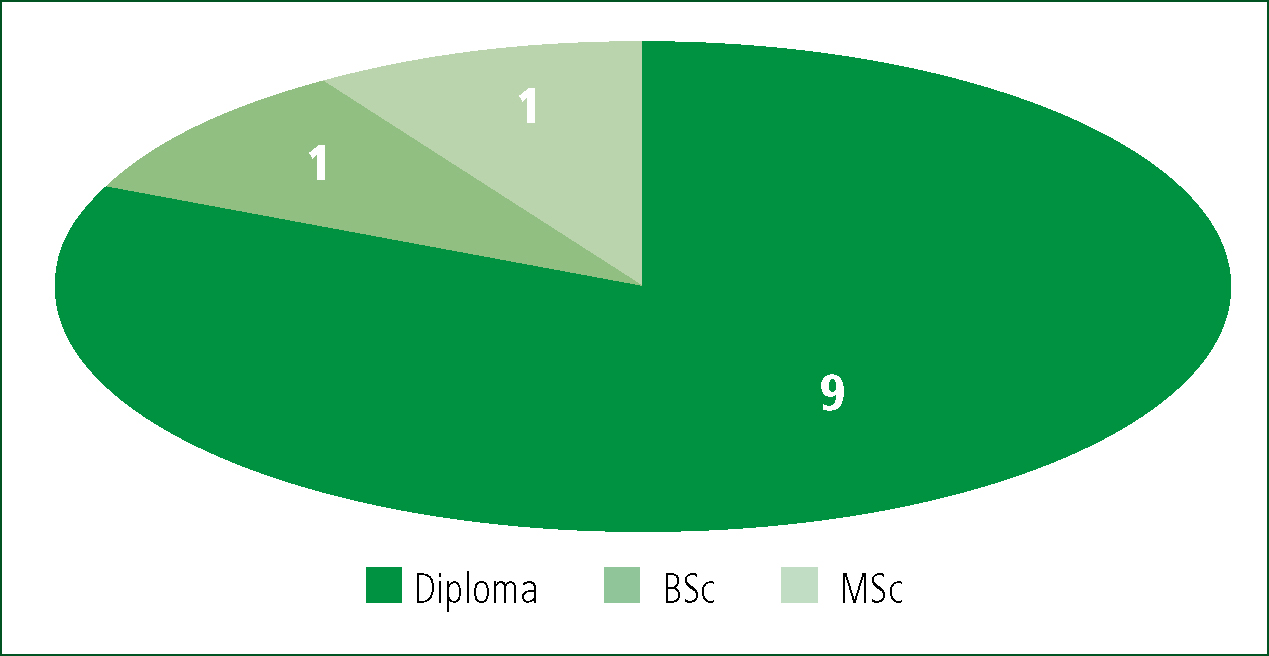

A total of 11 questionnaires were returned, generating a response rate of 33%. Ten respondents were male, with only one female respondent, and the mean age was 47 years old. All participants were registered with the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) and the average length of service was reported as being 13 years. The most common level of educational attainment was a higher education diploma (nine respondents), and all respondents reported having had exposure to DNACPR orders in their professional practice (Table 1). Likert-style questions were used to capture more subjective data, with the majority of participants strongly agreeing that they were comfortable with DNACPR orders (Figure 1).

| N | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age | 20–30 | 1 |

| 31–40 | 1 | |

| 41–50 | 5 | |

| 51–0 | 4 | |

| Gender | male | 10 |

| female | 1 | |

| Length of service | 0–5 years | 3 |

| 6–10 | 2 | |

| 11–19 | 3 | |

| 20–30 | 3 | |

| Educational attainment | Diploma | 9 |

| BSc | 1 | |

| MSc | 1 |

The research yielded four key themes (Table 2):

| Theme | Response exemplar |

|---|---|

| Communication | ‘GPs to make the service aware if one is in place so crews can be informed prior to arrival. Possibly some form of alert bracelet to identify patients in care homes, as staff are not always alert to the facts of patients with DNARs' (person 6) |

| ‘Early identification if one is in place to inform crews. To reduce responses to cardiac arrests where there is a DNAR in place’ (person 5) | |

| ‘Clearer instructions given to family/carers on the need to keep this form with the patient at all times. Too many times we go to patients who say there is a DNAR in place, yet cannot find it to produce it to ambulance crews' (person 8) | |

| Length of service | ‘Robust education with on-going up-dates. Education by NWAS should include a legal professional presenting this subject’ (person 1) |

| ‘More clear and defined guidance on what is treatable in a DNAR patient. More clear defined guidance to crews to clearly outline when its o.k to withhold treatment and let patient die’ (person 7) | |

| ‘Education with care services e.g. home care plans. That family members and health care professionals are aware of the circumstances and education of what is involved’ (person 11) | |

| Responsibilities | ‘Doctors sometimes leave the section on ‘review dates/indefinite’ blank! Does this mean the DNAR is invalid or not? If doctors don't fill in the form correctly in the first place then what chance do paramedics have on scene?’ (person 8) |

| ‘It could be handy if once the GP and patient decide to put one in place then the patient address was recorded by NWAS if we have to attend to the patient address in the future’ (person 2) | |

| ‘Should be proof-read before giving to patient, i.e. to ensure correctly completed and reviewed—especially open orders and review dates and that all questions are answered. Ensure that the GP who signs it knows what he is signing’ (person 4) | |

| Patient's wishes | ‘Respect patient's wishes’ (person 10) |

| ‘To opt out of aggressive treatment around infections’ (person 5) | |

| ‘Knowing patient's wishes in advance would make for improved quality of care, fewer A&E attendances and re-assurance for the paramedic knowing that they are acting in accordance with the patient's wishes’ (person 3) |

Communication

Communication was a recurring theme in the responses, with all research participants indicating a need for improved communication regarding the DNACPR process. The primary concerns concentrated on the need for more robust written instructions identifying that a DNACPR is in situ, and clearer instructions for the family and/or carers in the event of a patient's death.

Education/length of service

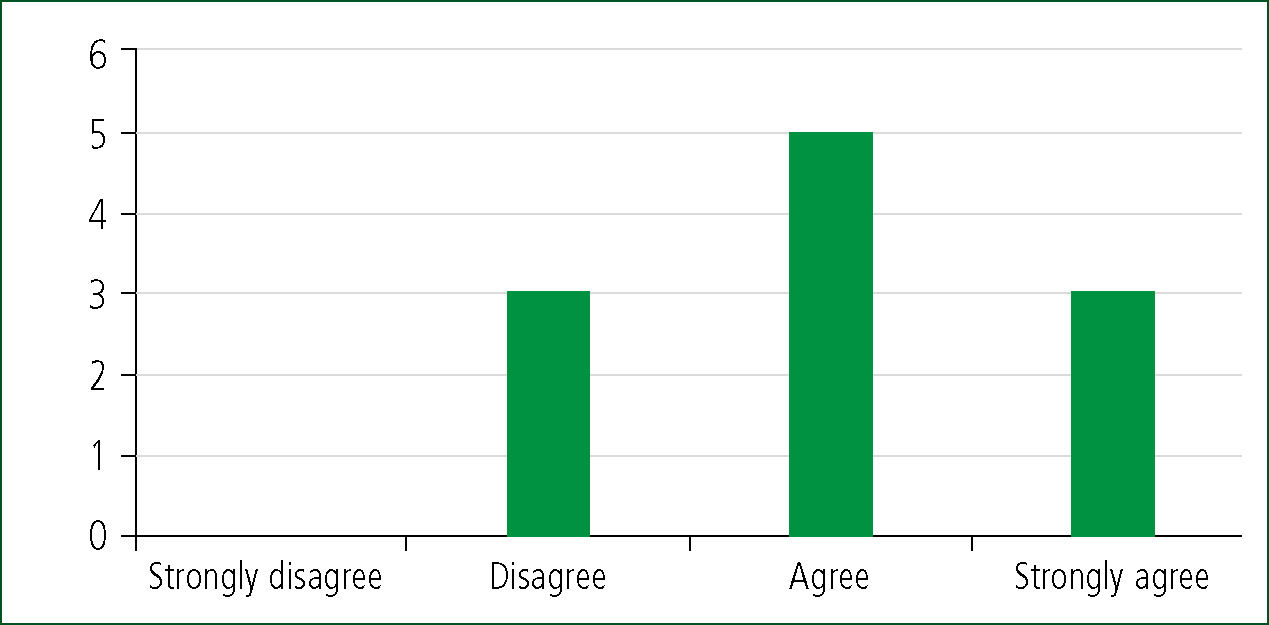

Responses concerning the level of educational provision in relation to DNACPR orders were more inconsistent, with three respondents suggesting that their training was insufficient; five indicating it had been sufficient; and only three responses strongly agreeing with the level of education received. Responses captured in the free-type boxes also identified a potential gap in education for patients and their relatives/primary carers, with some participants suggesting the need for contribution from representatives of the legal profession to training delivery.

Responsibilities

The study also identified that respondents were keen to promote individual responsibilities of those involved in the DNACPR process. A common thread from the research participants was the need to promote GP involvement, specifically in relation to holding individual conversations with the patient and ensuring that family members and allied health professionals were aware of the circumstances.

Patients' wishes

The need for patients' wishes to be respected was captured in the responses—the dominant themes being to allow patients to opt out of aggressive treatment, as well as articulating in advance how they wished to be cared for at the EoL.

Discussion

The parameters of the current study have been designed to address the gap in published research; yet consistencies exist with previous studies. This is most pertinent with regards to educational programmes for clinicians involved in the DNACPR process, as reflected in European studies conducted by Naess (2009) and Taghavi et al (2011), which indicated that participants felt there was a need to develop educational provision, comparable to the authors' findings. Identifying further similarities with the existing research base, Wiese et al (2012) called for greater involvement from the legal profession in the delivery of formal education around DNACPRs. Parallels can also be drawn with research involving allied health professionals such as general nursing grades (O'Hanlon et al, 2013), clinical nurse specialists (Boot and Wilson, 2014), emergency medical technicians (Norton et al, 2012), and community matrons (Kazmierski and King, 2015), all of which reflected participants' view of the need for improved education in EoL care.

In acknowledging the international contribution to the research base, what is absent in much of the existing published literature in relation to paramedics is the length of service and level of educational attainment of the participants. The notable exception is the research by Wiese et al (2012), which reported that 73% of respondents were older than 20 years of age, the majority of which had more than 10 years of occupational experience. Additional demographic information indicated that 98.5% were male, but no level of educational attainment was recorded (Wiese et al, 2012). This was concordant with the participant demographics in the current study, as there was only one female respondent out of 11, and all were aged 30 or older. Parity between the two studies can also be found in the length of occupational experience of respondents, although the level of educational attainment has to be considered in isolation—the majority of participants reported having a higher education diploma (Figure 2).

This may provide some substance as to why 91% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they were comfortable with DNACPRs in their clinical practice. With paramedic education in the UK now delivered through higher education, the concept of critical thinking and autonomy in practice has been given greater primacy in the paramedic curriculum than at any time since the evolution of the paramedic role in the early 1990s. A curious counter-point to this is reflected in whether respondents felt the level of training they received in relation to DNACPRs was adequate, with only 27% strongly agreeing it was, but the same number disagreeing with the statement. This is a significant finding—although it must be recognised that, overall, 72.7% agreed it was adequate (Figure 3).

Another of the study's key themes has been replicated in previous research in the form of communication issues. Earlier research has highlighted the importance of wider family involvement in the process (Gruzden et al, 2009; Waldrop et al, 2014; Mockford et al, 2015), and a number of participants in the current study used the free-type boxes on the questionnaire to reveal comparable sentiments. Developing this further, respondents also reflected the importance of respecting a patient's wishes at the EoL stage. However, paramedics did not always know what the patient's wishes were in terms of how they wished to be cared for. One possible explanation for this could be the variety and complexity of forms in existence for communicating DNACPR instructions—a phenomenon also noted in previous studies (Freeman et al, 2015; Mockford et al, 2015).

Despite moves towards a unified DNACPR form in the geographic region selected for the current study, no such document is currently in use. Electronic patient records are not widely available to emergency ambulance crews, and a lack of consistent mediums for communicating preferred EoL care also gave rise to some respondents noting the need for patients' wishes to be made known to ambulance crews.

A number of responses also made reference to the responsibilities of the patient's GP. Existing research does not universally make explicit the role of the GP in the health-care system involved, but a common thread in the responses for the current study was the importance of the involvement of the patient's own doctor. Comparisons with the existing evidence base become problematic owing to the paucity of research. However, with increasing emphasis on EoL care globally, a mandate exists for further attitudinal studies to embrace a wider focus, incorporating all components of the DNACPR process.

Implications for paramedics, educators and policy makers

The current study in isolation is unlikely to become a catalyst for a revised approach from educators and policy makers in the UK owing to its small scale. Key themes prevalent in the study's findings however have been replicated in other larger-scale studies, suggesting a degree of commonality concerning the dominant issues around DNACPR orders. Educational provision will perhaps evolve in tandem with an increased emphasis on EoL care, and more specifically, how patients can be supported more appropriately in the community (rather than during unplanned, unnecessary, admissions to treatment centres) (NHS England, 2013; 2014).

There are also procedural implications for ambulance services. A review of clinical protocols is essential to reflect the appropriateness of any intervention aimed at an attempted resuscitation of a patient at the EoL. There is a need to consider more critically what resource is most appropriate to respond to such scenarios (NHS England, 2017).

Strengths and limitations

The strength of the current study lies in addressing the gap in existing research, with the results complimenting the evidence base published to date. The notable limitation is the comparatively small number of paramedics invited to participate in the research project, with only two ambulance stations, from a total of eight in the same operational area, included in the study. There is also no means to confirm whether or not the responses provided reflect the paramedics' actual clinical practice, nor to capture the specific circumstances of each patient contact which have informed the paramedics' responses.

Unanswered questions

There is limited information from existing research in relation to the impact of a paramedic's educational attainment on their attitude towards DNACPRs. While some data can be extrapolated from the responses of the current study, questions remain as to the impact of formal educational programmes and, more specifically, what could be considered the optimum level of education to support a paramedic incorporating DNACPRs in their practice.

The demographic make-up of respondents clearly illustrates a majority of male participants; but what impact that had, if any, on their responses, is unclear. The influence of gender on attitudes concerning DNACPRs remains an area meriting further research.

The role of paramedics in EoL care varies according to the health-care system in which they operate, and the existing evidence base bears testimony to this. Reflecting this is the need for larger pan-European studies to capture what impact these differing contexts have on paramedic attitudes towards DNACPR instructions.

Research and recommendations

In addition to the influence of gender and the impact of sovereign health (and legal) systems, the co-relation between age and length of service provides a template for future research. The evidence base could further be developed through identifying the prevalence of advance care planning in regions with the greatest reservations/low levels of compliance with DNACPRs, and a review of formal curricular provision relating to EoL care.

In proposing any recommendations, it is incumbent on the researcher to synthesise the research findings with the existing EoL framework in England, while recognising the scope of practice of paramedics and the highly proceduralised environment in which they practice. It is also imperative to ensure that any recommendations on future strategy “…echo the true attitudes, beliefs and values of the participants' (Srivastava and Thomson, 2009:76).

The principal recommendation concerns regular curriculum guidance published by the professional body, The College of Paramedics. There is a need to accentuate the paramedic's role in EoL care, as well as incorporate advance decisions in the paramedic science curriculum and critique the legal, moral and ethical issues around their use. As the entry level of education into the profession continues to evolve towards a BSc by 2019, these curricular components should be developed in tandem with other elements of a paramedic's skill set and scope of practice.

To compliment this, future research should focus on further attitudinal studies to capture the ‘softer’ factors which invariably accompany a paramedic's decision-making at a patient's EoL. In developing the research base in this area, educational programmes could be tailored accordingly, and any procedural guidelines more sensitive to the thought processes involved.