The UK Search and Rescue (SAR) helicopter paramedic profession is at an exciting stage in its development. In the UK, there has been a recent transition from a predominantly military provision of service to a wholly civilian one. This transition has brought with it the introduction of greater diagnostic, monitoring and prognostic equipment. One such advancement is a wave-form end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2) monitoring capability.

EtCO2

EtCO2 is the concentration of CO2 in exhaled air, and approximates the partial pressure of CO2 in arterial blood (PaCO2). Values of PaCO2 usually range between 4.6-6 KPa (Valente, 2010; Pantazopoulos et al, 2015). EtCO2levels are dependent on tissue and lung perfusion, alveolar ventilation and tissue metabolism, and are measured using a capnometer (numerical or colour indication), or capnography (graphical and numerical display) device (Valente, 2010; Pantazopoulos et al, 2015). In awake, non-intubated patients, EtCO2 is typically slightly less than PaCO2 by around 0–0.3 KPa; but for the intubated or ill patient, the reduction can be circa 0.8 KPa (Valente, 2010; Pantazopoulos et al, 2015). During cardiac arrest, optimal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) only achieves around 25–40% of spontaneous cardiac output; as a consequence, EtCO2 levels are reduced (Pantazopoulos et al, 2015). The interpretation of these readings can offer an indication of aerobic metabolism and circulatory efficiency during resuscitation attempts.

Like many UK domestic ambulance services, core clinical guidance for the majority of the UK's SAR helicopter paramedics is contained within the Association of Ambulance Chief Executives' (AACE) and Joint Royal College Ambulance Liaison Committee's Clinical Practice Guidelines (AACE, 2016). This is supplemented by guidance published by the Resuscitation Council (UK) (RCUK) (2016a). Previously, these guidelines ‘strongly advised’ the interpretation of EtCO2 readings during cardiac arrest management (AACE, 2013: 34). The most recent updates have escalated its importance, as capnography is now described as ‘mandatory’ to confirm and monitor endotracheal tube (ET) placement (RCUK, 2015a; AACE, 2016: 41). The AACE and RCUK also recommend that EtCO2 monitoring is used to:

Although the AACE and RCUK prescribe the use of EtCO2 in cardiac arrest management, there appears to be a paucity in specific guidance with regards to its interpretation and application—they describe the ‘what’ and ‘when’, but not the specifics of ‘how’. The aim of the current paper is to address this by answering the following question:

‘How can EtCO2 measuring assist with CPR attempts in SAR Helicopter paramedic practice?’

Methods

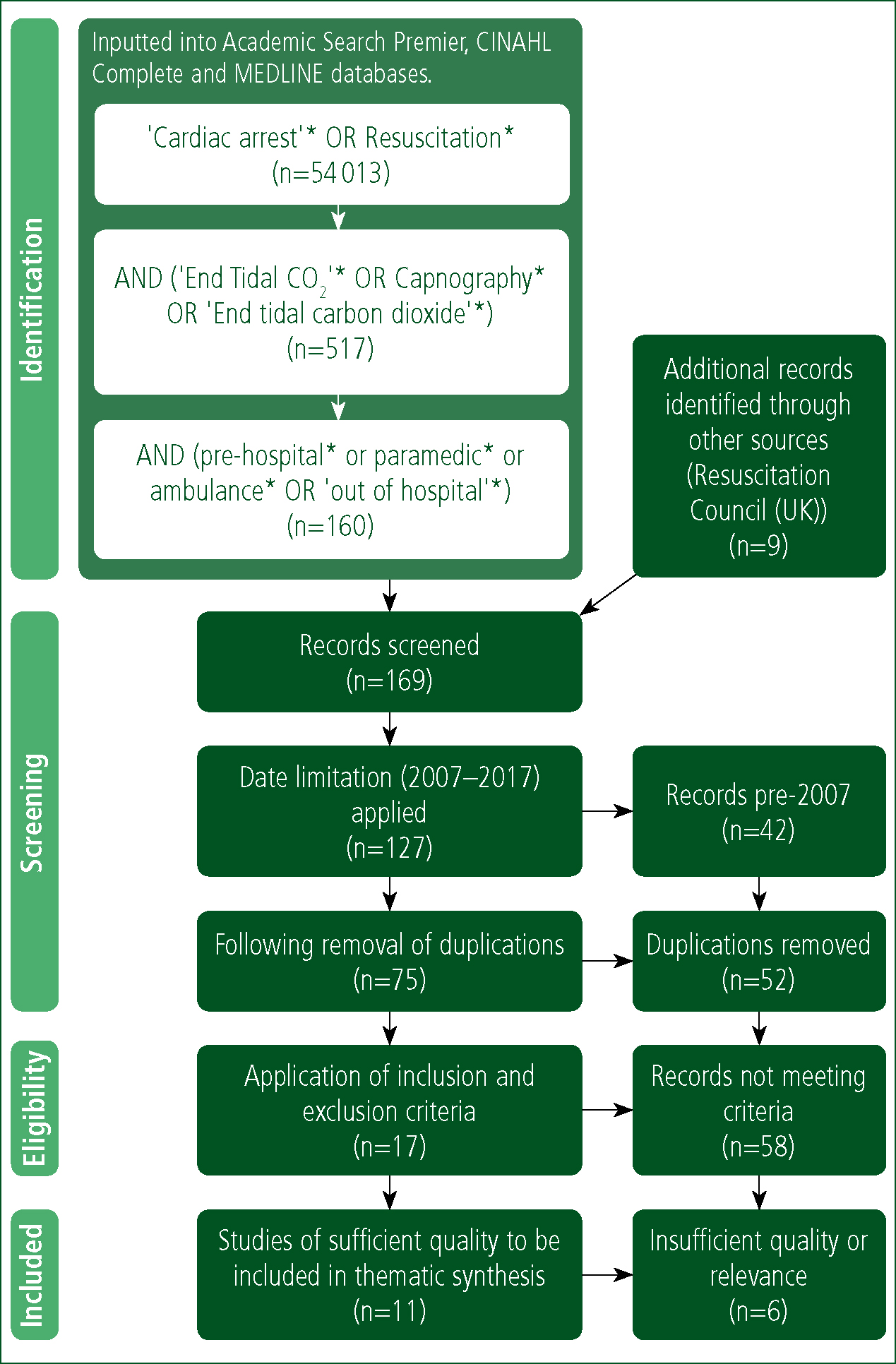

This review was conducted in a systematic manner using the PRISMA (2015) statement as a basis from which to approach the literature. To obtain evidence pertinent to the subject being investigated, the search terms listed in Figure 1 were inputted into Academic Search Premier, CINAHL Complete and MEDLINE with the period specified from 8 February to 2 February 2017. Only publications' titles were searched; no additional expanders or limiters were applied. In addition, the EtCO2 references cited in the RCUK's (2015b) Prehospital Resuscitation guideline were also included in the screening process (Figure 1). Eligibility was refined to recent papers of optimum contextual relevance by applying a date restriction (2007–2017) and an inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1). The resulting 17 papers were read in full and scrutinised for sufficient relevance and quality. To mitigate bias and promote critical systematism, the remaining 11 were critiqued using the Critical Appraisals Skills Programme (CASP) (2013a) checklists. A comprehensive critique of each paper was undertaken (available from the authors), and the following thematic synthesis was derived.

| Search identifier |

| Research involving the use of EtCO2during manual cardiopulmonary resuscitation. |

| Exclusion criteria |

| Research not focusing on the use of EtCO2 during manual cardiopulmonary resuscitation. |

Results

Prognostication

There were nine papers relating to the use of EtCO2 as a prognostic tool; eight of these were similar in their aims, design, parameters and execution (Grmec et al, 2007; Kolar et al, 2008; Lah et al, 2011; Herdadstveit et al, 2012; Ozturk et al, 2014; Sheak et al, 2015; Murphy et al, 2016).

All eight addressed a clearly focused question relating to the prognostic use of EtCO2 during out-of-hospital cardiac arrests (OHCA). Samples were either total population in nature or focused on specific arrest aetiologies, the majority of which were cardiac (Table 2). The ethics surrounding the study of cardiac arrest in human samples demanded that they were all descriptive and observational by design; ethical approval was either obtained or justifiably waived. Resuscitation attempts were performed in accordance with the nationally advocated guidelines of the studies' countries of origin; hence, each subject was treated in a relatively uniform manner. All papers clearly described appropriate methods for recording observations and data-linkage, including ensuring its validity and reliability. Grmec et al (2007), Kolar et al (2008) and Lah et al (2011) adhered to the Utstein recording criterion (Cummins et al, 1991). Justified explanations of their statistical analysis and significance tests were also included. Findings were suitably reported, aptly complemented by tables and graphs where appropriate. These design methods ensured adherence to the CASP (2013a) checklists, hence boosting validity and enabling strength to be attributed to their results (Meadows, 2003; Cutter, 2012a; Mooney, 2012). Results were both clinically and statistically significant. The overall, initial and final average EtCO2 readings were higher in those patients achieving an ROSC in all of the studies (Table 2). In the Lah et al (2011) study, the initial mean values of EtCO2 in those that had suffered an asphyxial arrest were unusually high, and did not show the significant difference between the ROSC and no-ROSC groups seen in the other studies (6.96±3.63 KPa versus 5.77±4.64 KPa; p=0.313) (Table 2). The difference was only significant after the fifth minute (6.09±2.63 KPa versus 4.47±3.35 KPa; p=0.006) and remained until final values of EtCO2 (5.87±2.14 KPa versus 0.55±0.49 KPa; p< 0.001) (Lah et al, 2011).

| Authors | n | Arrest aetiology | Average type | EtCO2 (KPa) in those who achieved ROSC | EtCO2 (KPa) in those that did not achieve ROSC | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Overall | |||||||

| Murphy et al (2016) | 230 | Cardiac | Median (range) | 4.3(0.7, 11.6) | 2.9(0.8, 10.3) | 0.0004 | ||

| Sheak et al (2015) | 356 | All | Mean (SD) | 4.6±0.6 | 3.1±1.8 | <0.001 | ||

| Heradstveit et al (2012) | 336 | Cardiac | Mean (SD) | 3.4±1.2 | 2.4±1.2 | <0.001 | ||

| 117 | Respiratory | Mean (SD) | 4.5±2.2 | 2.3±1.5 | <0.001 | |||

| 12 | Pulmonaryembolism | Mean (SD) | 2.2±1.0 | 0.9±0.5 | 0.023 | |||

| 110 | Other (non-traumatic) | Mean (SD) | 2.7±1.0 | 1.3±1.1 | <0.001 | |||

| Initial | Final | Initial | Final | |||||

| Grmec et al (2007) | 389 | All | Mean (SD) | 2.4±0.8 | 3.6±0.9 | 0.9±0.7 | 1.0±0.8 | <0.0001 |

| Ozturk et al (2014) | 97 | Non-traumatic | Mean (SD) | 2.5±1.2 | 4.9±0.6 | 2.1±1.1 | 1.6±1.0 | <0.05 |

| Kolar et al (2008) | 737 | Non-traumatic | Mean (SD) | 3.13±1.65 | 3.64±0.94 | 2.54±2.43 | 0.97±0.33 | <0.001 |

| Lah et al (2011) | 51 | Asphyxial | Mean (SD) | 6.96±3.63 | 5.87±2.14 | 5.77±4.64 | 0.55±0.49 | 0.313 |

| 63 | Cardiac | Mean (SD) | 4.62±2.46 | 4.99 ± 1.59 (p<0.001) | 3.29±1.76 | 0.96±0.39 (p<0.001) | 0.041 | |

| Eckstein et al (2011) | 3121 | Non-traumatic | Mean (95% CI) | 3.7(3.5, 3.9) | 2.1 (2.1, 2.2) | <0.001 | ||

Herdadstveit et al (2012) made a similar discovery; mean EtCO2 readings were higher in those with respiratory aetiology arrests compared with those of cardiac aetiology (3.5±2.2 KPa versus 2.8±1.3 KPa; p<0.001). Another anomaly was a significantly lower overall mean EtCO2 observed in patients with a pulmonary embolism (PE) (1.7±1.1 KPa; p<0.023) compared with respiratory (3.5±2.2 KPa; p<0.001) and cardiac aetiologies (2.8±1.3 KPa; p<0.001) (Herdadstveit et al, 2012). This pattern was present in both ROSC and no-ROSC cohorts (Table 2).

In the results (n=3.121) of the largest study of this kind, Eckstein et al (2011) discovered that an EtCO2<1.33 KPa (odds ratio 4.79; 95% CI=3.10–4.42) or an EtCO2 that fell by ≥25% of the baseline (odds ratio 2.82, 95% CI=3.10–4.42) were the variables most significantly correlated with not achieving ROSC. Grmec et al (2007), Kolar et al (2008) and Lah et al (2011) also discovered that no patient with an initial, average, final and maximum EtCO2 value of <1.33 KPa achieved ROSC. Hence, they proposed 1.33 KPa be used as a threshold for resuscitation attempts in the field.

Rognas et al (2014) tested the validity of this clinical prediction rule (CASP, 2013b). This multicentre, prospective, observational study collected EtCO2 and patient demographic data from cardiac arrest victims of all aetiologies. During the 21-month period, 595 patients suffered an OHCA, of which 358 had their airway managed with an advanced adjunct and accompanying EtCO2 readings. The study adhered to a consensus-based template for reporting (Sollid et al, 2009), thus significantly boosting its validity and reliability. Out of the 271 patients that had sufficient EtCO2 data to be included, 29 had an initial EtCO2 <1.3 KPa. Four of these (13%) achieved ROSC; hence the clinical prediction rule was refuted.

Only four of the eight prognostic papers investigated survival-to-discharge from hospital (Table 3). A similar prognostic pattern was evident in three of the studies—overall, or initial and final EtCO2values were higher in those who survived to discharge, versus those who did not. There was one exception; results in the Murphy et al (2016) study showed little difference between survival (3.1 (1.1, 6.4) KPa) and non-survival (3.4 (0.7, 11.7) KPa; p<0.001). This could be explained by Murphy et al (2016) opting to statistically analyse as a median and range; although easily calculated, it is vulnerable to outliers—this explains the relatively large data-spread as well (Walters and Freeman, 2015).

| Authors | n | Arrest Aetiology | Average Type | EtCO2 (KPa) Survival to discharge | EtCO2 (KPa) non-survival to discharge | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Overall | |||||||

| Murphy et al (2016) | 230 | Cardiac | Median (range) | 3.1(1.1, 6.4) | 3.4(0.7, 11.7) | 0.0004 | ||

| Sheak et al (2015) | 356 | All | Mean (SD) | 5.1±1.7 | 3.5±2.0 | <0.001 | ||

| Initial | Final | Initial | Final | |||||

| Grmec et al (2007) | 389 | All | Mean (SD) | 2.6±0.9 | 3.9±1.2 | 1.4±0.9 | 1.9±1.3 | <0.0001 |

| Kolar et al (2008) | 737 | Non-traumatic | Mean (SD) | 3.17±1.42 | 3.89±1.12 | 2.34±1.95 | 1.99±1.33 | <0.001 |

These results must also be considered alongside their limitations. In all studies, samples were limited to patients who met inclusion criteria with corresponding data of sufficient quality. This led to the exclusion of some data, rendering the sample susceptible to accusations of bias (Cutter, 2012a; Hunt and Lathlean, 2015). Control of some EtCO2 influencing variables such as chest compression (CC) uniformity, strict resuscitation guideline adherence, and the effect of cardiac arrest drugs, was outside the scope and resources of these studies, leading to questionable reliability and validity. Like all observational studies, they were vulnerable to recording and data-linkage errors (Cutter, 2012b; Booth, 2015). Nevertheless, the cumulative effect of these limitations did not appear sufficient to significantly detract from the strength otherwise attributable to these results, by virtue of their design strength and collaborative unanimity.

Early indication of an ROSC

Tat et al (2016) and Pokorna et al (2010) conducted multicentre, observational studies to evaluate the diagnostic characteristics of an abrupt rise in EtCO2 in relation to ROSC. Patients were resuscitated using nationally advocated guidelines, and augmented by a mechanical ventilator to regulate minute volume, thus enabling greater control of this EtCO2 determining variable. Those suffering OHCA cardiac arrests had data recorded in a standard cardiac arrest registry format.

Tat et al (2016) included 178 adults from a total of 548 non-traumatic arrest aetiologies; the remaining 370 had insufficient data. They discovered that an abrupt rise of EtCO2 was a specific but non-sensitive marker of ROSC in patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest—ROSC caused a sudden rise in EtCO2 but a sudden rise in EtCO2 was not always associated with ROSC. The diagnostic accuracy was higher in cardiac arrests with non-cardiac aetiology (sensitivity 45%, specificity 100%) compared to arrests of cardiac aetiologies (sensitivity 18%, specificity 97%). The median EtCO2 level immediately after ROSC was higher than the median level before (5.5 KPa versus 4.3 KPa, p=0.033).

This was corroborated by Pokorna et al (2010): 108 cases of all arrest aetiologies had either a single uncomplicated ROSC (n=59) or had no signs of ROSC and died (n=49); 32 did not meet this criterion and were excluded. Mean EtCO2 levels were 3.55±1.6 KPa before ROSC and 4.8±1.66 KPa after (p<0.0001). Mean difference before and after ROSC was 1.32 KPa (95% CI=0.86–1.8 KPa). The greater the abrupt rise in EtCO2, the less sensitive but more specific of ROSC this became. An abrupt rise in EtCO2 ≥2 KPa indicated ROSC with 49% sensitivity and 82% specificity.

Although minute ventilation was controlled using a mechanical ventilator in both studies, neither accounted for uniformity of CC and the effect of cardiac arrest drugs. In addition, the exclusion of patients from both studies makes them susceptible to sample bias (Cutter, 2012a; Hunt and Lathlean, 2015).

CPR quality

Murphy et al (2016) and Sheak et al (2015) also investigated the relationship between chest compression depth and EtCO2readings. Results in both studies showed a significant correlation between CC depth and an increase in EtCO2. In the Sheak et al (2015) OHCA sample, for every10 mm increase in CC depth, the mean increase in EtCO2 was 0.2 KPa (p<0.001). CC depth also had the greatest association with a change in EtCO2 in the Murphy et al (2016) study; a 10 mm increase in CC depth was associated with a 3.6% increase in EtCO2 (95% CI 1.9%, 5.4%; p=0.0001).

Discussion

The studies in the current review revealed that variables such as arrest aetiology, efficacy of CC, and timeliness of resuscitation efforts affect EtCO2 levels. All studies unanimously agreed on the principle that CO2 coming out of an ET indicated its correct positioning. The RCUK (2016b) offers further guidance to account for residual CO2 in the stomach or oesophagus, stating that CO2 coming out of the ET after six ventilations indicated that it was in the trachea. For an intubated patient undergoing CPR during a SAR mission where auscultation is difficult, if there is no CO2 coming out of the ET, it should be removed.

Those with higher EtCO2 values unanimously had a more favourable prognosis in terms of achieving ROSC and survival-to-discharge. An EtCO2<1.33 KPa, or an EtCO2 that fell by ≥25% of the baseline, were the variables most significantly correlated with not achieving ROSC. Some studies suggested these parameters should be used as resuscitation attempt thresholds (Grmec et al, 2007; Lah et al, 2011). However, EtCO2 is context-specific and, although unlikely, outliers can achieve ROSC outside of these parameters (Rognas et al, 2014). Hence, rather than generalising specific cut-offs, the contextualisation and interpretation of trends appears more appropriate. This sentiment is echoed by the RCUK (2015a), which suggests that specific values should not be used in isolation as an indication to terminate resuscitation; readings should be part of a multimodal approach to decision-making.

SAR paramedics manage a relatively large number of drowning victims. The unusually high initial mean EtCO2reading observed in the no-ROSC asphyxial group is of particular relevance (Lah et al, 2011). This initial misleading and optimistic reading can be attributed to an accumulation of CO2 as a result of its production and delivery with an absence of ventilation prior to arrest (Valente, 2010; Pantazopoulos et al, 2015). EtCO2 readings in these patients only offered prognostic value once this was overcome—typically after 5 minutes (Lah et al, 2011). Although not as significant to SAR helicopter paramedic practice, the EtCO2 levels in PE arrests typically appear pessimistic throughout. This is owing to a sustained diminished pulmonary perfusion (Rumpf et al, 2009; Valente, 2010).

When faced with diminishing EtCO2 readings, knowledge of the correlation between EtCO2 values and CC depth may prompt SAR helicopter paramedics to increase CC depth, or change a tiring CC provider. A sudden rise in EtCO2 was a highly specific but non-sensitive marker of ROSC (Pokorna et al, 2010; Tat et al, 2016). This confirms the rationale that CPR is not as effective as spontaneous circulation in terms of cardiac output (Valente, 2010; Pantazopoulos et al, 2015). If a sudden rise is observed, clinicians may consider delaying the administration of drugs until after the next indicated pulse-check to mitigate potentially harmful and unnecessary administration of adrenaline in a patient with ROSC (RCUK, 2015a). A SAR helicopter is a vibrating and turbulent platform. If the ability to palpate a pulse is deemed futile in this setting, consideration should be given to limiting attempts to only if patients display an abrupt rise in EtCO2, thus minimising deleterious interruptions in CC.

Delays in defibrillation, or even short interruptions in CCs, are ‘disastrous’ for patient outcomes; hence, every effort must be made to ensure continuous CCs are maintained and timely defibrillation occurs (Soar et al, 2015:106; RCUK, 2016b; 2016c). However, without a mechanical CC device, it is impossible to prevent short interruptions in CC or defibrillate while winching or carrying a patient to a SAR helicopter (Figure 2a; Figure 2b). The same is true (but to a lesser extent) when offloading from landing sites into an awaiting ambulance or onto a hospital trolley. As well as using EtCO2 readings to enhance their resuscitation skills, SAR helicopter paramedics can use high or improving EtCO2 values (thus a favourable prognosis) as an indication to persevere with resuscitation attempts in situ (if able) on a patient that would otherwise have been winched or carried to the aircraft sooner. This would mitigate unnecessary deleterious interruptions in CCs for viable patients.

On the contrary, during risky rescue missions where EtCO2 readings indicated further resuscitation, attempts would most likely be futile. SAR helicopter paramedics can justifiably initiate immediate transfer to the aircraft or terminate rescue attempts. This aptly works on the premise that the patients' chances of survival should be proportionate to the associated dangers to justify resuscitation attempts in hazardous situations or to conduct a risky winch recovery.

An SAR helicopter mission is a clinical, rescue and aviation equipoise; this involves deciding ‘what’, ‘when’ and ‘where’ within rescue and aviation limitations (Griffiths, 2015; 2016; 2017) (Figure 2c). As a consequence, one of the most highly prized attributes of the SAR clinician is his or her ability to manage the emergency scene in this context. The application of the results of this literature review will serve to improve resuscitation skills and, more importantly, inform the decision-making process to optimise overall outcomes for both patient and rescuer when managing cardiac arrests during SAR helicopter missions.

Limitations

As an undergraduate project, a comprehensive systematic literature review was beyond the scope and resources (Hek and Langton, 2000). The results examined studies of varying arrest aetiologies and had insufficient raw data. It was neither possible nor appropriate to conduct a statistical meta-analysis (Deeks et al, 2011).

The studies were non-randomised and non-blinded; their position on typical evidence hierarchies is comparatively low. There was a paucity of results relating to the early indication of ROSC and quality themes; results only yielded two papers for each theme.

Conclusion

EtCO2 readings offer a surrogate indication of circulatory efficiency, aerobic metabolism and efficacy of ventilation during resuscitation attempts. Despite the limitations of the current review, and the respective limitations of the studies it yielded, sufficient strength can be attributed to the results.

Capnography is mandatory to confirm ET placement, and CO2 coming out of an ET tube indicates that it is in the correct position. Victims of cardiac arrest with higher EtCO2 values typically have a more favourable prognosis in terms of achieving ROSC and survival-to-discharge. An EtCO2 value of <1.33 KPa or an EtCO2 that falls by ≥ 25% of the baseline are the variables most significantly correlated with not achieving ROSC. Awareness and application of the prognostic value of EtCO2 readings inform decisions about patient care and rescuer safety when managing cardiac arrests during SAR helicopter missions. Diminishing EtCO2 readings may be an indication to increase CC depth, or change a tiring CC provider to optimise CPR attempts. A sudden rise in EtCO2 is a highly specific but non-sensitive marker of ROSC.

Interpretation and application of the results of the current literature review promote greater adherence to the principles of evidence-based practice (Sackett et al, 1996). This will enable the conscientious, judicious and explicit use of current best evidence to make decisions about the care of individual cardiac arrest patients, on a case-by-case basis, in the context of a SAR helicopter rescue mission in the UK.