Cauda equina syndrome (CES) is a rare neurological emergency that both authors have seen within the last 3 years of clinical practice, and both feel, from their own experiences of paramedic education, is not currently covered sufficiently.

This article will look at CES in two parts. Firstly, it will establish what is meant by CES, how it can be suspected at pre-hospital examination, and what actions should be taken when a clinician suspects CES. It will then look at medico-legal issues of CES as well as considering the consequences of a delayed diagnosis.

What is the cauda equina?

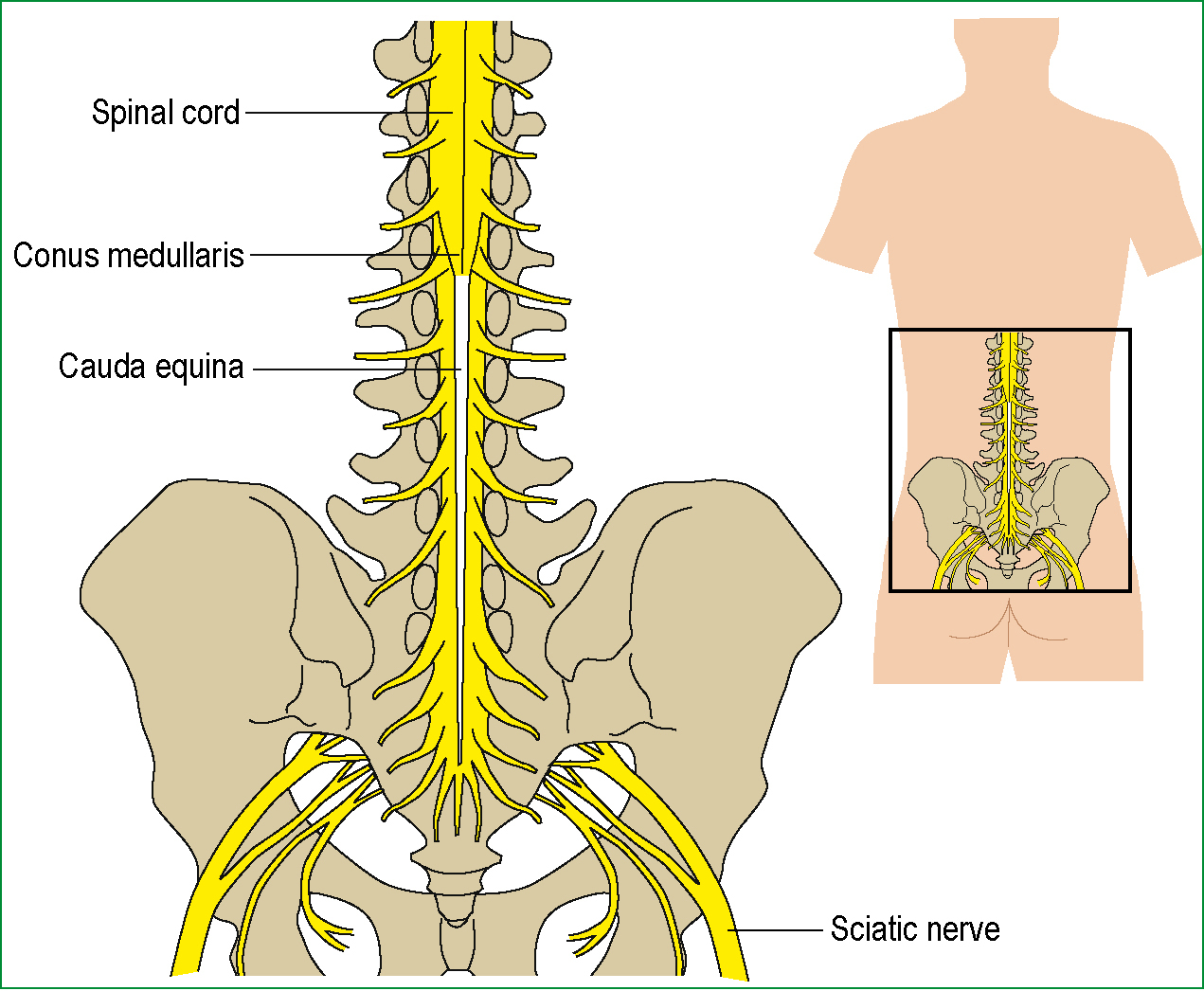

The spinal cord descends from the base of the medulla oblongata in the vertebral space, terminating approximately two thirds of the way down the vertebral column at the level of the second lumbar vertebra, although this can vary from between the twelfth thoracic vertebrae and the third lumbar vertebrae (Coggrave, 2011). From this point of termination, known as the ‘conus medullaris’ (Tortora and Derrickson, 2011), the nerve roots, which will go on to become the lumbar sacral and coccygeal nerves, descend downwards through the vertebral column before exiting at the respective vertebrae. As the nerves descend form the conus medullaris they fan out inside the vertebral column to create the appearance of a horses tail, known as the corda equina (Coggrave, 2011) (Figure 1).

The nerve roots which comprise the cauda equina are responsible for both the afferent and efferent neurological pathways of the lower limbs, perineum and sphincters of the urinary tract and rectum/anus (Gitelman et al, 2008).

Cauda equina syndrome

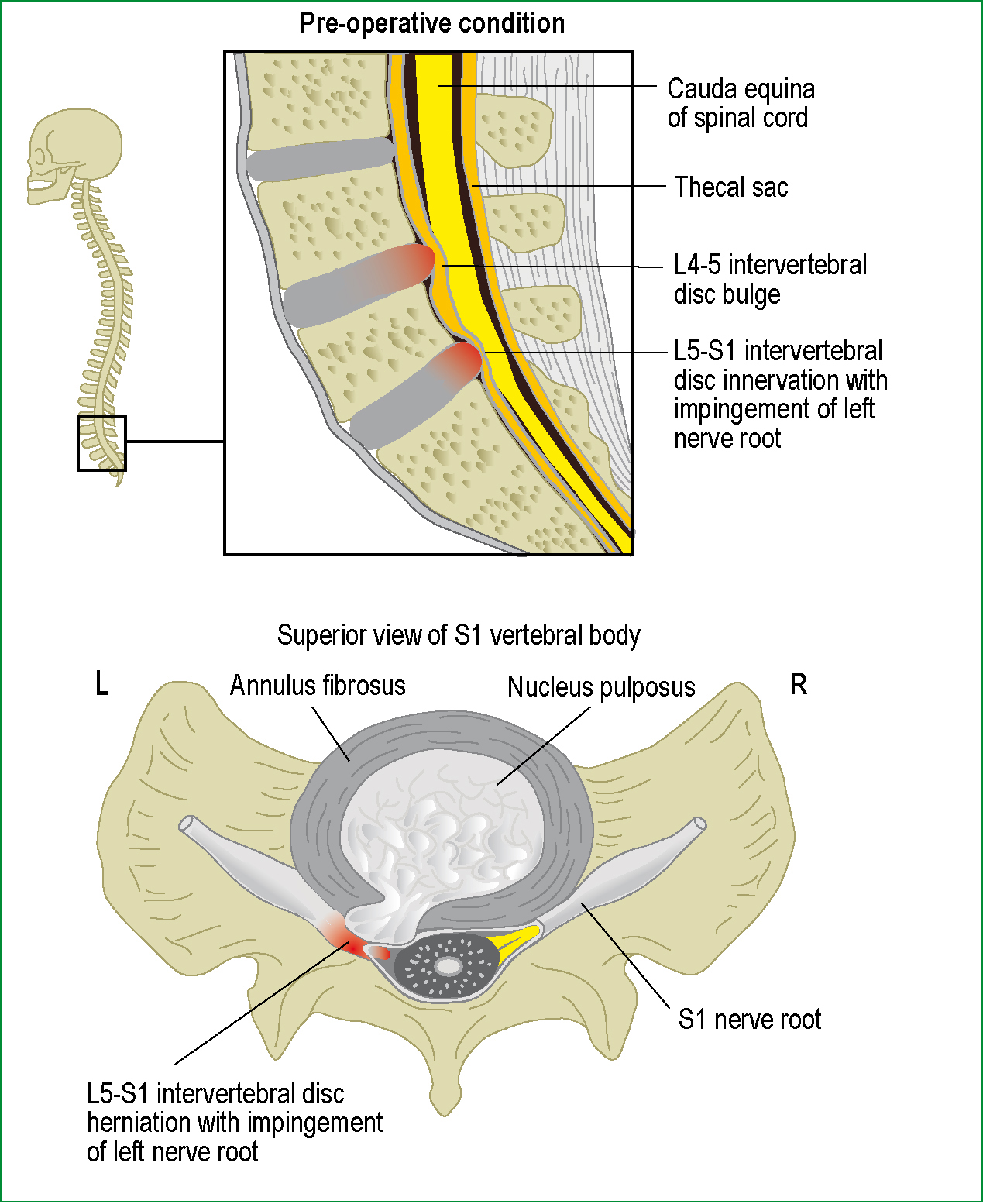

CES, which was first reported in 1934 by Mixter and Barr, occurs when the nerves within the corda equina region are compressed. This compression most commonly arises from a central lumbar disc herniation (Ellanti and Lenehan, 2012), especially around the region of L4/5 and L5/S1 (Lavy et al, 2009) (Figure 2).

When they occur, the vast majority of disc herniations are lateral and therefore compress individual nerves after they have separated from the cauda equina; however, in around 3% of cases disc herniation's are central and, rather than compressing on the lateral nerves, pressure is applied to the entire cauda equina (Stewart, 2001). As the nerves are located inside the vertebral column they have no room to expand, it is this compression and subsequent interruption of nervous pathways that leads to CES. Left untreated, CES can lead to permanent paraplegia and the loss of bowel and bladder control.

Whilst disc herniations are the most common cause of CES, there are a number of less common causes, including epidural haematoma, infection, tumors, trauma (Table 1), post-surgical procedure, post-spinal anaesthesia, gunshot wounds and in extremes even constipation (Gardner et al, 2011).

| Severe low back pain |

| Sciatica: often bilateral but sometimes absent, especially at L5/S1 with an inferior sequestration |

| Saddle and/or genital sensory disturbance |

| Bladder, bowel or sexual dysfunction |

Epidemiology

CES is a rare condition, which presents mainly in adults but can occur at any age (Tidy, 2009), and has an overall incidence that is estimated to be from 1 in 33 000 to 1 in 100 000 of the population.

A retrospective review conducted in Slovenia found an incidence of CES, resulting from disc prolapse, of 1.8 per million of the population (Podnar, 2007).

As above, lumbar disc herniation is the most common cause of CES but there is a significant variation as to the estimated incidence of CES caused by herniation. Estimations range from 2% of all herniation's going on to cause CES (Samandouras, 2010) down to 0.12 % (Lavy et al, 2009), although the authors of this latter study felt this was an underestimation and planned further work.

As part of the literature search, this article attempted to find data linking CES presentation to ambulance services, but none was found. It is worth noting, however, that both authors have encountered at least one case of CES confirmed by neurosurgical units within the last 3 years of clinical practice.

Signs and symptoms

Shi et al (2010) describe how the typical presentation is with the classic triad of saddle anesthesia, bowel and/or bladder and/or sexual dysfunction and lower extremity weakness. This is consistent with the list of red flags provided by Gardner et al (2011) (Table 1), which practitioners should be aware of when assessing back pain or performing neurological examinations.

Fehlings et al (2005) provide a more comprehensive list of common symptoms that can be indicators to the need for urgent surgical decompression, which include: progressive paralysis, difficulty initiating micturition, retention or incontinence of urine, altered bowel function, saddle area anaesthesia, loss of sphincter control and impotence.

Gitelman et al (2008) describe how CES is clinically classified into one of two categories, either incomplete or true retention. Incomplete CES, known as cauda equina syndrome incomplete (CESI), or CES with true retention, known as cauda equina syndrome retention (CESR). The differentiation between CESI and CESR is the degree of retention the patient experiences. In CESI, the patient can present with a number of sensory and motor changes, including saddle anaesthesia, but does not yet have full retention or incontinence of urinary or bowel functions. In CESR the patient has developed true retention, this leads to painless urinary retention and eventually overflow incontinence. Similarly, either retention or incontinence of the bowel may be experienced.

It is not necessary for paramedics to distinguish between CESI and CESR, but to recognise and initiate transport remains the priority whenever CES of any form is suspected.

Although CES most commonly presents acutely as a result of a lumbar disc herniation, it can occur after a long history of chronic back pain with or without sciatic pain, or more insidiously with slow progression to numbness and urinary symptoms (Lavy et al, 2009; Waterhouse and Pellatt, 2011), and should always remain a differential diagnosis when examining patients with back pain of any kind.

To illustrate the nature of cauda equina, which can present in an atypical presentation, there is a case report by Ellanti and Lenehan (2012) of a 32-year-old patient initially presenting to an emergency department complaining of lower abdominal pain. On further examination it was found that the abdominal pain was due to urine retention and that the patient also had back pain and altered sensation in both lower limbs; these symptoms had seemed insignificant to the patient due to the severity of the abdominal pain. The authors subsequently conclude that anyone presenting with abdominal pain of an unknown cause and/or a history of back pain should undergo a neurological examination as well as an abdominal examination.

Pre-hospital recognition

Understanding what CES is as well as the likely signs and symptoms should increase the opportunity for pre-hospital suspicion of the condition to be established. In the authors' experiences, paramedics see a significant number of patients presenting with non-traumatic lower back pain, although a literature search did not reveal any current reliable data on this. However, given the experience of the authors and the epidemiology figures discussed above, it is reasonable to suggest that the consideration of CES should become a routine differential diagnosis in the assessment and management of back pain, especially where a herniated disc is thought to be likely.

Assessing or questioning patients specifically about any feelings of saddle anaesthesia and micturition habits and whether there have been any changes are vital. Paramedics are not expected to provide a definitive diagnosis of CES, they do however need to recognise the limitations of their practice and seek advice or refer patients when appropriate (Health and Care Professions Council, 2012b). In this case, any suspicions of CES using the red flags and symptoms described above should act as an indicator to initiate transfer to a suitable receiving unit.

The main investigation a patient with suspect CES requires is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to identify any compression of the cauda equina nerves. A patient with suspected compression will need to be conveyed to an appropriate emergency department with access to MRI. If a paramedic had a choice of emergency departments at different hospitals and one of the hospitals had a specialist neurosurgery unit, then a suspected CES patient should be conveyed there, as confirmed CES secondary to disc prolapse is one of the few spinal surgical emergencies (Todd, 2005).

Management

It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss in detail the management of CES, which is managed as a specialist neurosurgical condition. Nonetheless, it is worth understanding that the primary treatment revolves around surgical decompression in some cases. The key point to note here is that when a patient is suffering CESI the priority is to prevent it from progressing to CESR, with current literature recommending early decompression (Gittelman et al, 2008).

Ahn et al (2000) performed a meta-analysis on 322 patients who had CES. They found that there was a significant advantage to treating patients within 48 hours compared to those treated after 48 hours following the onset of CES. Specifically, they found a considerable improvement in the recovery of motor, sensory and sphincter deficits in those patients who had received decompression surgery within 48 hours of onset.

The authors of this article can identify no specific pre-hospital treatment that improves outcomes for CES, but it is worth reiterating that outcomes for many patients relies on urgent surgery, so early accurate recognition of the condition and transport to an appropriate receiving unit is the focus of pre-hospital management.

Medico-legal issues

When conducting literature searches for the writing of this article the authors noted a large proportion of articles relating to medico-legal claims and CES, so for this reason a brief summary of medico-legal issues is included here.

Samandouras (2010) says that a large proportion of claims linked to CES relate to the delayed diagnosis and management of CES, and as many as 50% of cases brought for these reasons are successful.

Gardner et al (2011) describe how in 2004 the Medical Defense Union, one of the leading professional indemnity societies, identified 62 CES-related claims. At the time they published their article, 42 had been concluded, with damages being paid in 20 of them, which equates to 48% payout vs. a usual settlement rate of 34% of all other claims. The average settlement at the time (2003 prices) was £336 000. Just under half of these cases related to incorrect or delayed diagnosis, most frequently in the primary care setting.

If a pre-hospital clinician did not recognise early symptoms of CES and failed to transport a patient appropriately, it could clearly lead to a significant delay in their diagnosis and reaching definitive care, potentially leading to a claim of malpractice.

Against a background where many ambulance trusts are encouraging the see and treat agenda, paramedics must be mindful of their responsibility to practice within their scope of knowledge, skills and experience, and fulfill their duty to refer on any patient they are not confident in managing (Health and Care Professions Council, 2012a).

Conclusions

CES is a rare but serious neurological condition, and paramedics need to be able to suspect and identify the need to transfer patients to appropriate receiving units. A patient needs to undergo urgent assessments to determine whether they have CES, and if confirmed, this is a neurological emergency that may require urgent surgery. Any delay in treatment can have a devastating effect on the patient's long-term prognosis, and they can be left with motor, sensory and/or sphincter deficits.

Further work is required to accurately establish the frequency of presentation to ambulance services of patients suffering from CES. It is not currently possible to establish the likelihood or frequency with which pre-hospital practitioners may encounter this condition, but the experiences of the authors, along with the potentially devastating consequences of missing the appropriate clinical impression, make it justified to suggest that CES becomes a key differential diagnosis when assessing patients with back pain, and that this condition should become a feature of all modern paramedic education curricula.