The COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak was first recognised by the World Health Organization (WHO) on 31 December 2019 and declared a global pandemic in March 2020 (Cucinotta and Vanelli, 2020). The respiratory virus at the centre of this international public health emergency is a variant of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) known as SARS coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (WHO, 2020).

At its height, the COVID-19 pandemic placed extreme demand upon the healthcare system across the UK. This created additional difficulties for the ambulance service, which reported a rise in calls about patients with breathing difficulties and related symptoms (Public Health England, 2020). Capacity issues led to patients having to be treated in ambulances while awaiting handover for extended periods of time (Mahase, 2020) and an increase in interhospital critical care transfers (Pett et al, 2020).

A common life-threatening complication of COVID-19 is the development of severe hypoxaemic respiratory failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (Tzotzos et al, 2020). The management of ARDS typically involves treatment of the precipitating cause and the use of a lung-protective artificial ventilation strategy (Griffiths et al, 2019).

In mechanically ventilated patients with ARDS, the use of prone positioning has been demonstrated to improve mortality in several studies (Guérin et al, 2013; Munshi et al, 2017). The improved oxygenation seen in prone patients with ARDS is attributable to better ventilation-perfusion matching. The prone position allows expansion of the dorsal lung areas where the biggest recruitment of alveolar space can occur. The dorsal lung is not impeded by any other anatomy within the thoracic cavity. This effect on anatomy is thought to improve oxygenation and the mechanics of ventilation via three mechanisms (Guérin, 2017):

Traditionally, prone positioning is a highly coordinated procedure performed on ventilated patients by teams in intensive care units. However, there is growing evidence that this position is of benefit in awake patients with COVID-19 as a simple, safe and effective technique to improve oxygenation in those unresponsive to initial therapy (Cohen et al, 2020; Damarla et al, 2020; Wendt et al, 2020; Winearls et al, 2020).

This technique has also gained attention in the media, with several news outlets reporting its use in patients with COVID-19 (Cohen, 2020). Additionally, recent systematic reviews on the use of awake prone positioning for patients with COVID-19 have found this strategy may improve oxygenation and reduce the need for intubation (Anand et al, 2021; Pb et al, 2021).

Consequently, protocols incorporating awake prone positioning alongside various respiratory therapies have been adopted in emergency departments (Caputo et al, 2020; Jiang et al, 2020). In January 2021, the WHO (2021) published a conditional recommendation to consider the use of awake prone positioning in severely ill hospitalised patients with COVID-19. Finally, a recent case series by Maehlen et al (2021) proposed that repositioning cooperative patients into a prone position may be an effective strategy in the prehospital critical care management of those with severe hypoxaemia because of COVID-19.

The objective of this study is to explore ambulance clinician awareness of awake prone positioning and their experiences of its use in their practice. The authors hypothesise that prone positioning is a procedure that has been brought to the attention of ambulance clinicians through the media and medical literature, and has been used as a treatment strategy in patients with suspected COVID-19 who are unresponsive to standard therapy. The authors believe that this has been happening despite any formal guidance on indications for the prehospital use of the procedure, or assessment of feasibility and patient safety.

Methods

The study design was a cross-sectional survey, structured and reported using the ‘Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology’ (STROBE) guidelines (Cuschieri, 2019) and distributed to operational ambulance clinicians working for the South East Coast Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust (SECAmb). Approval to undertake the study was provided by the Healthcare Research Authority (IRAS ID: 295324) and the SECAmb research and development group.

The SECAmb operational area covers a geographical region of 3600 square miles and provides an emergency ambulance service to a population of 4.8 million people across Kent, Surrey, east and west Sussex, and north-east Hampshire. The Trust employs more than 4000 staff, of whom almost 90% are in operational roles (SECAmb, 2022).

An online survey (Appendix 1; available online) was designed by the study team and created using Microsoft Forms A total of 3377 operational staff across the trust were emailed a link to complete the survey. The link was also placed in the weekly staff bulletin. All staff in a frontline ambulance role were eligible to respond to the survey, and taking part was voluntary. Consent to participate in the study was gained upon opening the survey, with participants unable to proceed to the survey questions if consent was not provided.

An online assessment of study ethics was performed, and an NHS research ethics committee review was not required. Approval to undertake this study was provided by the Healthcare Research Authority and SECAmb Research and Development Group. No patient involvement or access to patient details were required and no patient identifiable data were collected.

A 28-day response period was chosen to provide an adequate opportunity for staff response. The survey was accessible only to respondents with a trust NHS email account. The survey software limited responses to one per account and automatically anonymised the data. Several questions allowed multiple choice answers and additional comments could be made via a free-text option upon completion of the survey.

Clinicians were asked to report on any cases in which they used the prone position for patients with suspected COVID-19 they attended from 1 January 2020 to the date of survey closure. To mitigate the risk of reporting bias, the survey provided opportunities to report both negative and positive experiences.

Data were collected in Microsoft Excel and reviewed by the study team throughout the collection period. Numerical data were obtained using the survey software and analysed in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Additional free-text comments were manually reviewed by the study team to assess for themes.

Results

A total of 279 operational staff accessed the survey, with 278 (99.6%) consenting to participate, giving a response rate of 8.2% of all staff contacted. The majority of these respondents were paramedics (61.2%). Non-registrant roles of emergency care support worker, associate ambulance practitioner and ambulance technicians represented 11.5%, 9.7% and 4.7% of respondents respectively. Advanced paramedic roles included critical care paramedics (6.5%) and paramedic practitioners (5.4%). A minority of respondents (1.1%) did not state their scope of practice.

Of all respondents, 229 (82.4%) were aware of the use of the prone position for awake patients with COVID-19, while 49 (17.6%) respondents stated they were not aware of this practice. Of those aware of awake prone positioning, 18 (7.9%) had used this in their practice when attending patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19.

Where prone positioning was used

Twelve respondents (67%) performed prone positioning on the ambulance stretcher including during transport. Five (28%) performed it on scene only and one (6%) used it on the ambulance stretcher only while stationary.

Whether difficulties or concerns were experienced

Thirteen of the 18 respondents who had used prone positioning did not report any difficulties or patient safety concerns. Three were concerned over anticipated difficulties in delivering clinical care in the event of deterioration, and two said the patient was reluctant to adopt the position.

Themes from free-text responses

A total of 24 free-text comments were made and reviewed by the study team. The majority of these were clarifications or further details expanding on survey answers.

Comments were categorised into the following themes: explanation of safety concerns (n=9); statements supporting the use of prone positioning (n=4); respondent advising they did not perform prone positioning as no clinical guidance was available (n=3); respondent advising they had no awareness of prone positioning (n=3); details of personal experience of prone positioning (n=3); and suggestions for further research (n=2).

Discussion

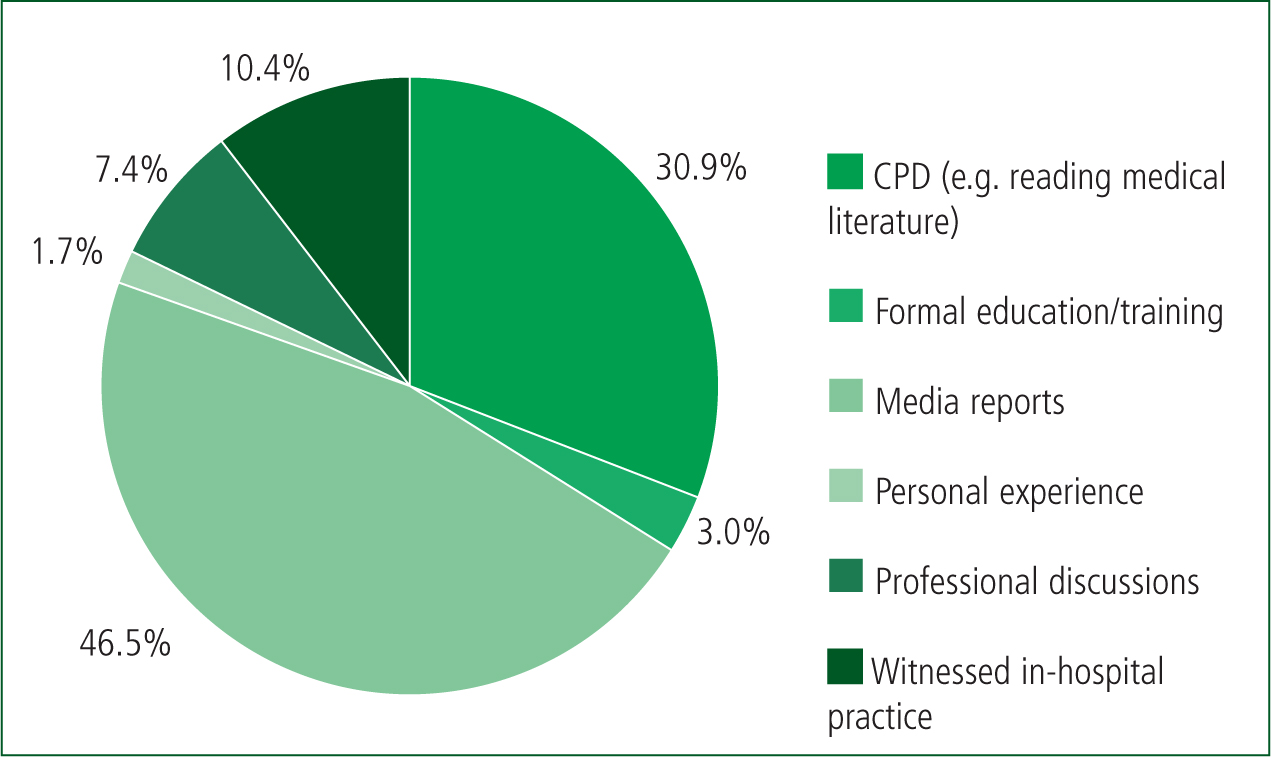

This study found 82.4% (n=229) of respondents were aware of the use of awake prone position in patients with COVID-19, with 7.9% (n=18) using it in practice. More than three-quarters (77.8%; n=178) of respondents who were aware of awake prone positioning had become aware of this practice through reading media reports or medical literature, with just 3% (n=7) reporting they had received any formal training (Figure 1).

Outside the intensive care unit, management of patients with respiratory distress in the prone position is uncommon and, before the COVID-19 pandemic, there was little literature or guidance on the subject.

The prehospital management of patients with breathing difficulties involves sitting the patient upright (Association of Ambulance Chief Executives, 2019) and no specific instructions relating to the use of the prone position have been made by ambulance service advisory groups in the UK.

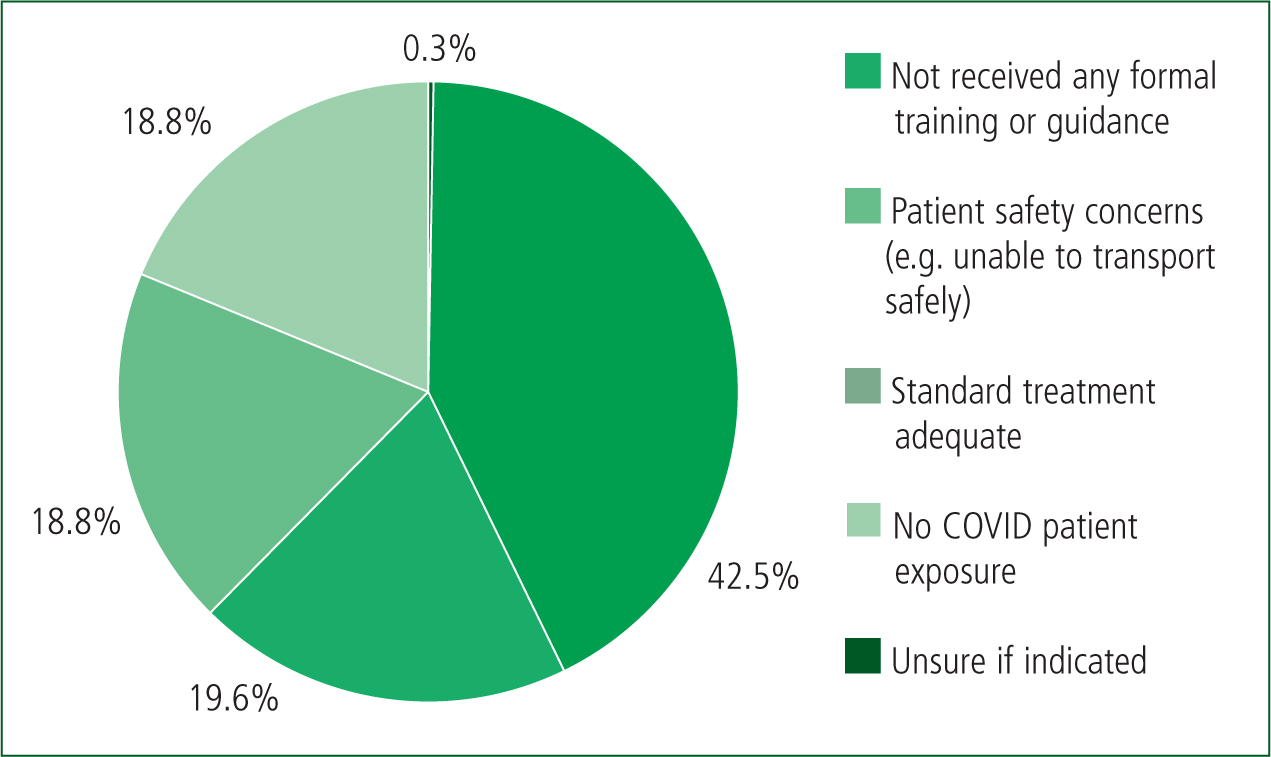

This is reflected in the results, as the lack of formal training or guidance in the procedure was the most frequently reported reason for not initiating prone positioning (Figure 2). However, these results have demonstrated that ambulance clinicians have become aware of this practice, through self-directed study or other avenues including personal experience, and considered or used it in patients with COVID-19.

Consequently, the authors believe this study may provide an example of how the healthcare challenges created by the COVID-19 pandemic have contributed to a greater use of ‘clinical courage’. This term describes the actions of health professionals faced with situations where the clinical needs of patients require the delivery of care beyond their level of formal training or guidelines (Konkin et al, 2020).

Clincal courage is likely to occur frequently within paramedic practice because of the wide range of situations arising in the prehospital arena, although it perhaps remains underreported through fear of reprimands (Mallinson, 2020). The authors feel accounts of such practices are important for several reasons, such as to identify potential areas of unmet or suboptimal care needs, to ensure patient safety is maintained and to highlight requirements for education or adaptations to guidance.

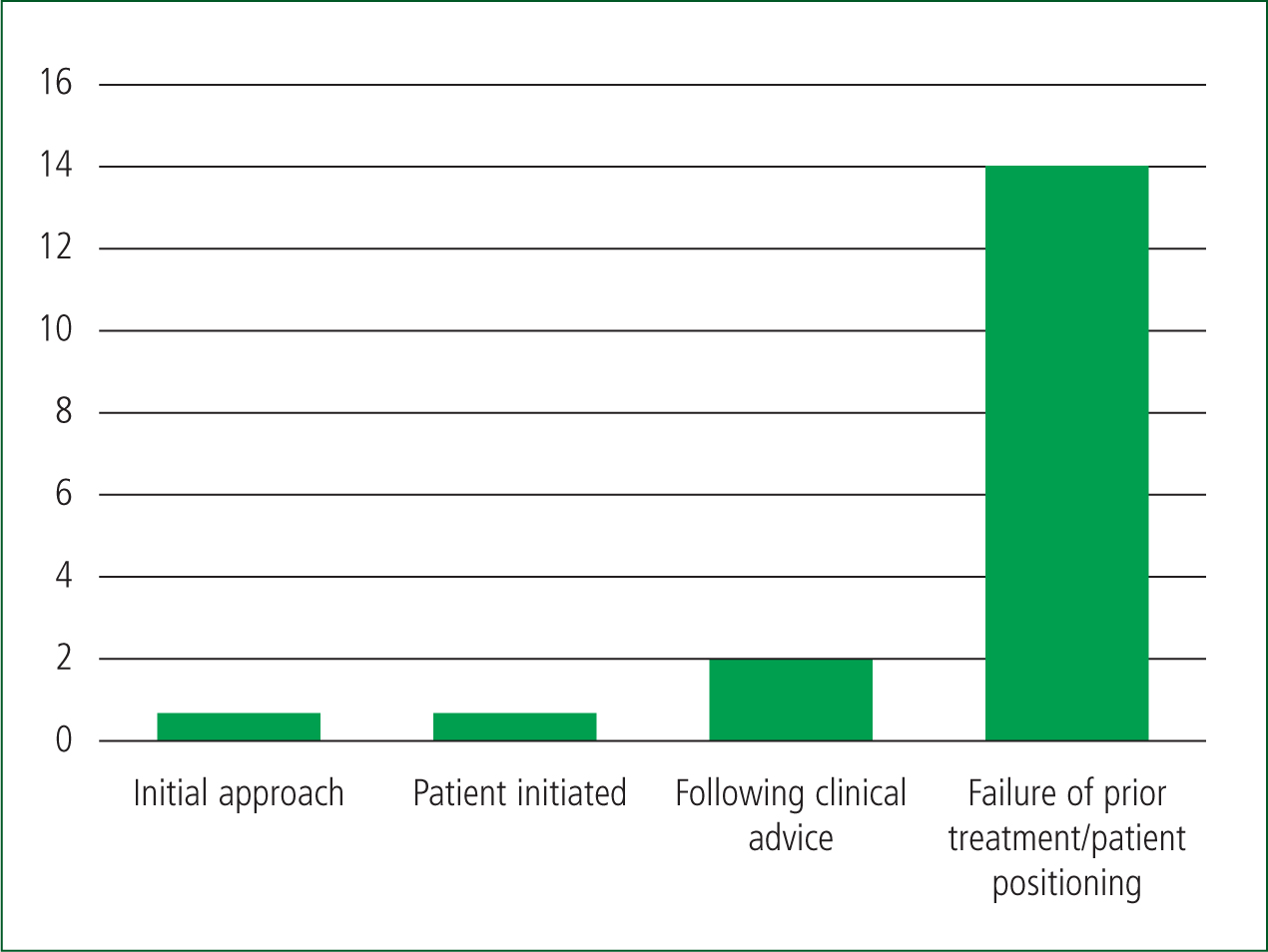

From these results, it seems that prone positioning was used in a stepwise approach to patient management rather than being the first treatment to be initiated (Figure 3). This further supports the theory that prone positioning was an act of clinical courage, and attempted once the practitioner had exhausted the options in their practice guidelines. The reasons for this are multifactorial, however, and these results show that the lack of formal guidance contributed to hesitation to perform proning in 42.5% (n=156) of respondents.

The opportunity to document previous treatment for COVID-19 was not specified in the questionnaire. It is assumed standard treatment would include oxygen therapy, nebulisation if required and positioning the patient in an upright position to optimise respiratory mechanics and gas exchange. The results show that 18.8% (n=69) of respondents reported standard treatment was effective so there was no need for alternative therapy.

Prone positioning was undertaken most frequently on an ambulance stretcher during transportation, with 63% (n=13) of uses being recorded in this circumstance. This may suggest prone positioning was possibly initiated before and during transport after standard interventions on scene had failed or were inadequate, and this was cited as the most common justification for ambulance clinicians initiating prone positioning in this survey. Of those who had used prone positioning, 32% (n=5) of respondents report using it at the scene of the emergency call.

Further research may explore if use was based upon the recommendation of prone position as a position of comfort for patients with mild symptomatic COVID-19 who were being managed in the community, or if this was as a temporising measure in severely unwell patients before transportation to hospital.

Concerns over patient safety were a frequent reason for not initiating prone positioning (Figure 2). Furthermore, 3 out of 18 respondents who used prone positioning described concerns over anticipated difficulties of delivering clinical care in the event of patient deterioration. As with every medical procedure, the risk of potential harm must be balanced with anticipated advantages. Risks in prone positioning may include vomiting, thromboembolism, discomfort, worsening clinical signs and pressure ulceration (Coppo et al, 2020). To avoid these potential risks, several contraindications to prone positioning are listed within the available guidelines (Box 1) (Intensive Care Society, 2020; May and Smedley, 2020).

Consideration should also be given to the application of the recommended five-point safety restraint system used for most ambulance service stretchers, as this was the most common factor described in the free-text responses related to safety concerns. No mentions of concerns of this nature have been made in previous studies on the prone transport of ventilated patients; however, the majority were undertaken in ambulance vehicles specifically designed for critical care transfer purposes.

Hersey et al (2018) suggested a checklist and protocol for the safe transfer of mechanically ventilated patients in the prone position. The adoption of a similar process guided by clinical simulation may be suitable to ensure the safe transfer of awake patients in this position.

Several respondents also reported concerns over increasing patient anxiety if the prone position was used. Therefore, future research exploring the experiences of those who have received this intervention may be of value when designing guidance for prehospital use.

Eighteen respondents (7.9%) reported they had used awake prone positioning for patients with respiratory distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. This was most often because previous treatment had failed.

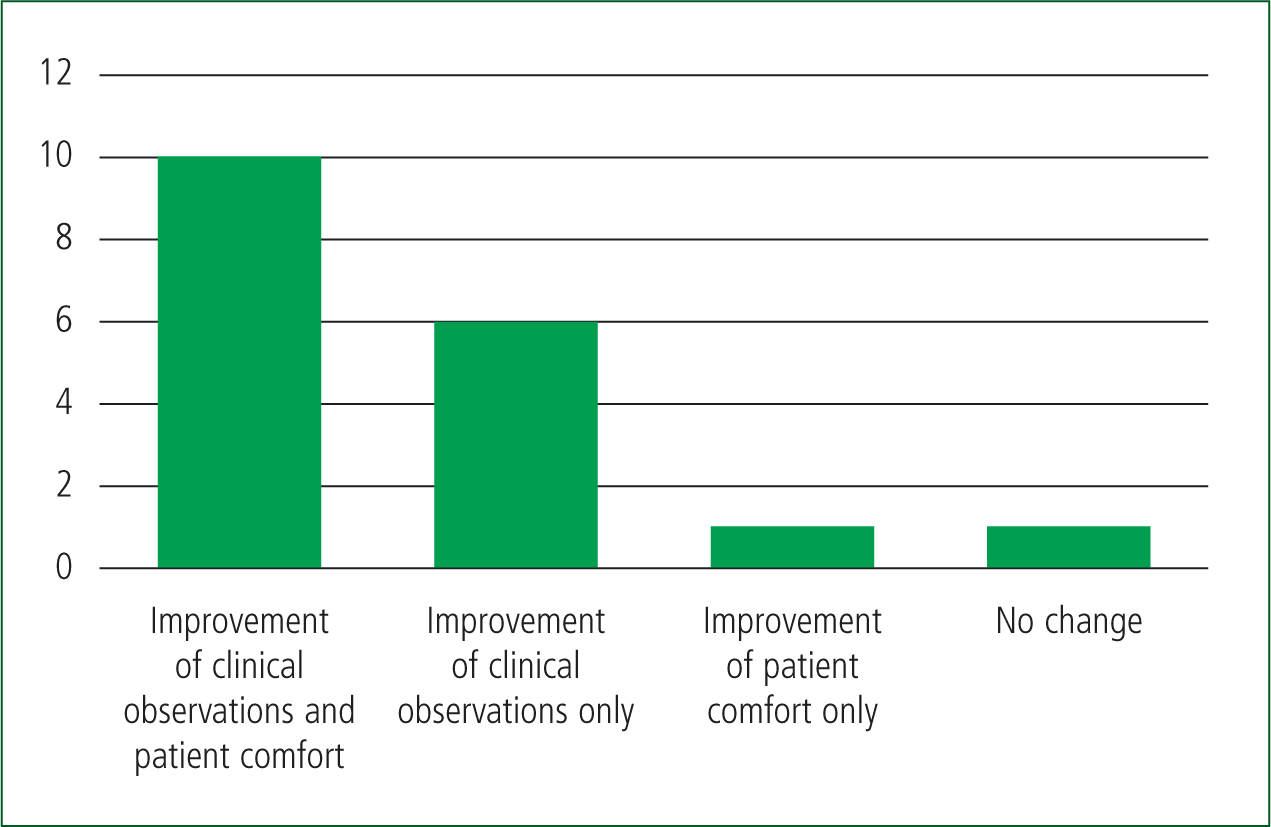

Ten respondents noted an improvement in clinical observations and patient comfort, with a further six respondents recording an improvement in clinical observations alone (Figure 4). One patient showed signs of improved comfort without improvement of clinical observations. This suggests the majority of clinicians observed physiological improvement and/or an increase in patient comfort following the adoption of the prone position. However, because of the small sample size and absence of clinical data, this observation cannot be used to draw conclusions on the clinical efficacy of prone positioning.

Nonetheless, these observations are not unique and reflect previous findings examining the clinical effects of the prone transfer of awake patients with COVID-19. Şan et al (2021) reported the blood gas values of 21 awake patients with probable COVID-19 before and after ambulance interhospital transfer in the prone position. This study found patients who had been transported in the prone position for longer than 15 minutes had improved oxygen satuation (SpO2) and partial pressure (PaO2) values on arrival at the receiving hospital. The present study did not collect clinical data, and the research by Şan et al (2021) includes a small number of patients. Therefore, larger studies of the physiological impact of this position during ambulance transfer and the effect of transfer duration may provide better insight into the clinical benefits.

One respondent reported no change in patient condition or comfort following the use of prone positioning. Although this study was not designed to investigate the clinical impact of awake prone positioning, it is reassuring to note it did not appear to cause discomfort or clinical deterioration. All patients were awake and cooperative, which may reflect use in patients with lower disease severity than mechanically ventilated patients.

Several questions remain over whether awake prone positioning should be routinely adopted into prehospital practice. Ambulance clinicians are often faced with undifferentiated patients in the community, in whom a diagnosis of COVID-19 or ARDS is not always certain, and therefore could be at risk of starting an inappropriate or untested treatment. Diagnosis of ARDS in the prehospital setting is problematic because of the requirements for imaging and blood gas interpretation. Furthermore, in patients with respiratory distress, there are often multiple differential diagnoses, which may cause further diagnostic uncertainty.

The ability to transport a patient safely in this position or move them back to a supine position in the event of deterioration during transport may also be problematic. Nonetheless, in settings such as an ambulance interior, where close supervision and monitoring is possible, and if used on conscious patients who are able to self-manoeuvre into the prone position, the authors feel the potential benefit of improved oxygenation may outweigh the risks and is worthy of further exploration.

Limitations

This study was limited primarily by the nature of the survey. Convenience sampling was used, with the survey distributed to the staff of one ambulance service in the south east of England. Therefore, results are at risk of a non-generalisability bias across the target population (Jager et al, 2017).

Additionally, at the beginning of 2021, the south east was the centre of a highly transmissible variant of COVID-19. Using volunteer sample participants also runs the intrinsic risk of bias through drawing those with a specific interest in the topic, further confounding the representation of the data and experiences gathered. Consideration should be made to the risk of anchoring and confirmation bias amid a pandemic, which may influence clinicians to form a sole diagnosis of COVID-19 in patients who have yet to receive formal diagnosis (DiMaria et al, 2020).

Thought should be paid to the fact that an absence of guidance advocating prehospital conscious prone positioning may affect an individual's response to the survey to avoid criticism. However, the anonymous nature of the survey may have protected against this.

Finally, this study did not explore patient outcomes or undertake patient follow-up, including diagnostic confirmation of COVID-19, in those who were in a prone position. Therefore, no conclusions regarding clinical efficacy can be drawn.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates ambulance clinicians are aware of the use of the prone position for patients with COVID-19 and a small number have used it in practice, despite a lack of training or formal guidance for prehospital use. The majority of clinicians who were aware of the procedure did not use it for this reason as well as because of concerns over patient safety.

When attempted, the use of prone positioning in prehospital practice provides an important example of clinical courage, and the perceived requirement from clinicians to adapt the clinical care they deliver in response to an unprecedented situation.

In patients who were treated and transferred in the prone position, improvements in clinical observations and patient comfort were reported in 16 out of 18 patients. If prone positioning is to be routinely used in practice, it would be prudent to provide clinicians with guidance based upon existing protocols, such as those published by the Intensive Care Society (2020). The use of simulation and dedicated transfer teams may allow the development of a protocol for safe use of the prone position in ambulance transfer.

Before prone positioning can be routinely implemented in prehospital practice, further research is required in a number of areas. These include the collection of clinical data to evaluate the impact of this intervention during ambulance transfer, vehicle-based simulation to guide protocols that ensure patient safety and qualitative research investigating the patient experience. JPP