Approximately 450 million people worldwide are affected by mental, neurological, or behavioural problems at any time (World Health Organization, 2015). In addition, the prevalence of crises, with acute psychological and behavioural manifestations, is increasing.

Given the continued transition between inpatient and community-based mental healthcare and the ongoing shortage in service provision, the NHS highlights that an increase in the urgent and emergency nature of mental health referrals is impacting emergency services, who inevitably pick up some of the shortfall (Xanthopoulou et al, 2022.

Many of the people requiring emergency or crisis mental health intervention may have physical health needs, which places them in a vulnerable position due to a continued lack of parity between physical and mental healthcare (Care Quality Commission (CQC), 2020) It is vital that care is needs-led and that first responders are trained and aware of the impact of physical and mental health comorbidities so that they treat with dignity and respect while also upholding human rights (Launders et al, 2022).

Paramedics and police are often the first responders, spending upwards of 40% of their time responding to mental health crises (Hallett et al, 2021). Their increased exposure to this patient cohort has received much attention; however, discussion in the literature within the past has focused on the psychological effect upon practitioners because of their chosen profession, particularly considering that of the emergency services (Mildenhall, 2012; Granter et al, 2019).

Evidence shows that paramedics are largely forgotten in the discussion about resource allocation and support, with much of the narrative focused on acute and hospital emergency department deficits as opposed to the first responders (Lawn et al, 2020)

There are increasing calls (World Health Organization, 2010) for first responders to be trained to support those in acute emotional distress, with many reporting a lack of skills and understanding of the mental health systems as causes of frustration and poor outcomes (Xanthopoulou et al, 2022).

NHS England has been called on to ensure 280 000 more people living with severe mental illness have their physical health needs met by 2020–2021, via better detection and access to evidence-based assessment and intervention (Mental Health Taskforce, 2016). While the Department of Health and Public Health England (2016) have published guidance on how mental health nurses can help improve the physical health of people with mental health problems, this has not been provided to the ambulance service, despite the increasing role it plays in supporting public health and primary care. Because of the nature of public and first-responder encounters within which paramedics mainly work, they will often meet people who are emotionally charged, highly aroused and psychologically distressed, whether this is through mental illness or psychological stressors.

To manage such encounters, it is crucial that preregistrants are equipped with the knowledge and skills to interact with patients experiencing turmoil and potential crisis. There are calls in the literature for first responders to develop their understanding and application of the key principles of skills such as de-escalation with the aim of improving response and reduce the likelihood of adverse outcomes (Puntis et al, 2018).

The authors had identified from previous cohorts that students felt ill-prepared to manage individually in this area. As they had supernumerary status during placement, they felt they could not take the lead in engaging with such people unlike the registered staff supervising them, which created a practice-theory gap.

Simulation gives students opportunities to develop technical and non-technical skills through the recreation of an experience that is as close to reality as possible (Bradley, 2006). Students learn, drawing on previous knowledge and experience to construct new knowledge through experience and exposure. Key to this process is reflection ‘in action’ and ‘on action’, as scenarios unfold and learners are subsequently debriefed. This facilitates the transformation of experience into practice-based knowledge (Schön, 1987).

Chadwick and Withnell (2016) identified that activities such as role play with trained people or paid actors, films, videos, patient manikins and computerised physiological models varied the degree of fidelity or realism afforded by simulation. These were categorised into: low-fidelity simulation, such as films or videos; intermediate-fidelity simulation, for example using manikins; and high-fidelity simulation, which could include advanced computerised models or human patient simulation/role play.

At the University of Surrey, academics have long taught theoretical components interprofessionally to share expertise, with the aim of increasing student comfort with the wide variety of patient cohorts and those with shared characteristics. A programme of immersive simulations was implemented by the mental health nursing and paramedic programme teams to give controlled but high-fidelity exposure where students could apply the theories and frameworks of communication and interaction that they had previously learned. Considering the psychological underpinning of the illnesses that the teaching was targeting, high-fidelity scenarios with actors were designed to challenge students' communication strategies and techniques under the supervision of the teaching team.

In addition to giving exposure to such patients, the authors aimed to evaluate how such simulated practice could affect individuals' confidence in interaction with these patients beyond the end of the exercise.

Methodology

This evaluation is a descriptive account of the implementation of a training session to develop student self-perceptions of self-awareness and self-regulation in encountering clinical situations where people presented in high states of arousal and there was potential for conflict.

To evaluate the training session and its value, students were asked to self-evaluate their confidence and knowledge both before and after the teaching exercise to facilitate ‘in action’ and ‘on action’ reflection.

De-escalation training

Paramedic science students participated in an online and face-to-face session focusing on conflict resolution and crisis resource management, which had an emphasis on soft clinical skills, such as interpersonal communication and developing an awareness of how to engage with people in a high state of arousal.

This involved discussion of the affective model (Kaplan and Wheeler, 1983) and how, as clinical professionals entering situations, paramedics can act as triggers and raise arousal levels. Discussions focused upon how one may manage this and avoid increasing arousal, plus techniques for reducing arousal in unfamiliar situations.

The face-to-face session then used actors and realistic environments to give students, working in pairs, the opportunity to implement such techniques while being remotely viewed and observed by tutors and peers. Coaching of actors by tutors ensured students had to constantly apply personal skills and awareness to manage the situation. All parties returned to the classroom after each scenario to debrief and discuss learning points collaboratively across tutors, students and actors.

Participants

For several years, mental health students at the University of Surrey had undergone de-escalation training, which has proved vital in preparation for practice. During cross-theme, inter-professional sharing, it was considered a key area of learning for paramedic science students.

Students from the paramedic science degree course participated in a de-escalation training simulation as part of a course requirement. Those in their third year of study were chosen as the cohort because learning was aligned to the module specifics and facilitated individuals' development to practice care independently under controlled circumstances, appropriate to their level of study. No personal, identifiable data were collected.

Exercise evaluation

Seventy-six students who undertook training as part of the module chose to provide feedback.

This training was evaluated to establish if it would prove beneficial to students. The rationale was to establish whether training would be effective and well received. Two aspects of student perception were collated to understand this.

First, student self-perceptions of self-awareness were assessed via a written questionnaire with the same five questions before and after de-escalation training. The qu estions focused on the following:

Students were asked to self-assess their ability around and awareness of de-escalation against predefined criteria of good, adequate, or limited. Numerical grading was attributed to these criteria: 3=good; 2=adequate; and 1=limited.

Second, students were asked to enter free-text answers to four questions. Two questions were asked before the training: ‘Do you feel prepared for today's session?’ and ‘What are you hoping to gain from the session?’ Two were asked after the session: ‘What will you take away from today's session?’ and ‘What other learning would you like?’

Analysis

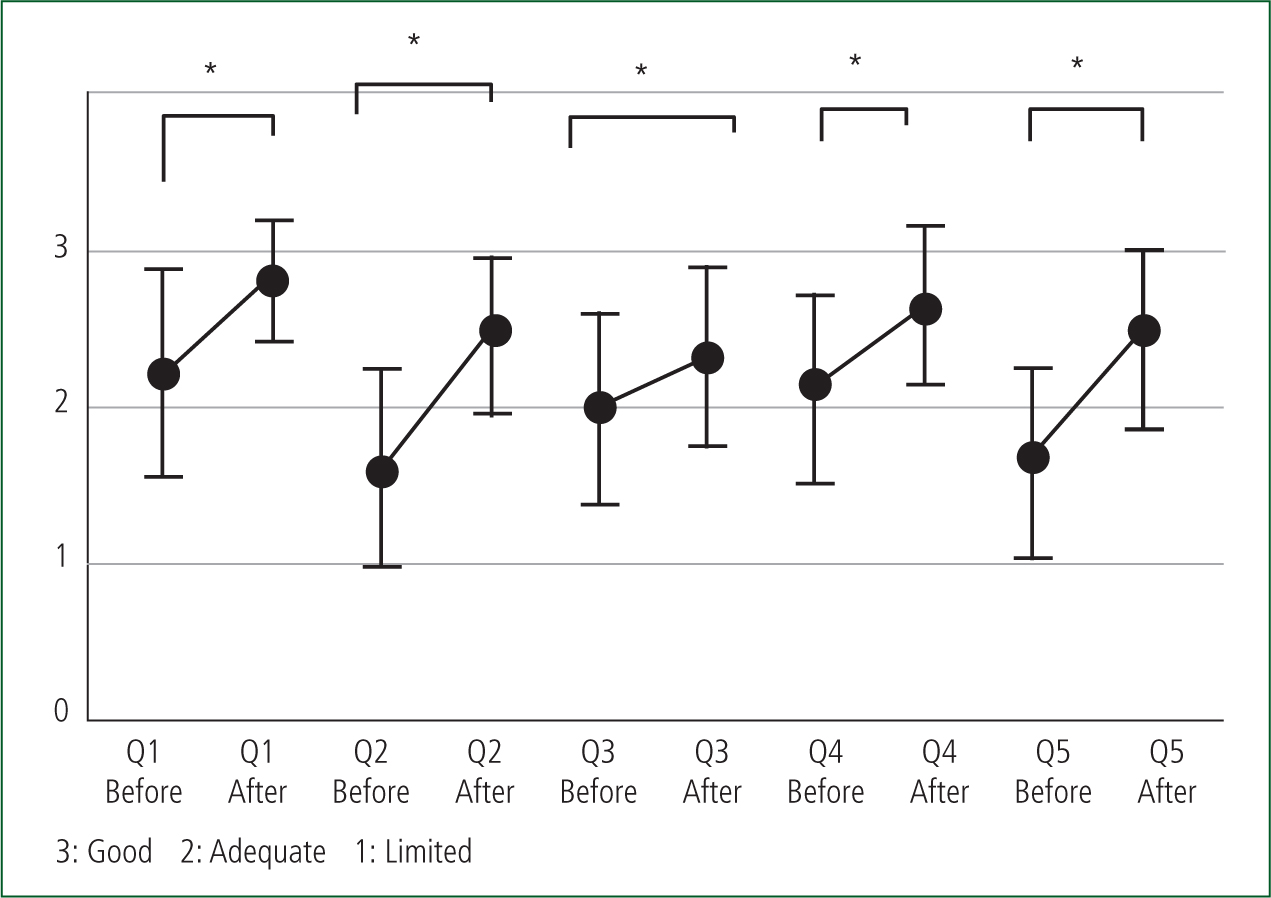

Pre- and post-statistical analysis was carried out to evaluate whether the teaching had had a positive impact. As a measure of robustness, numerical self-perceptions of self-awareness scores are presented descriptively, with mean (nearest whole figure) score (± standard deviation). Table 1 provides a detailed percentage breakdown of students' self-perceived ratings before and after training.

| Questions | Good (3) | Adequate (2) | Limited (1) | Mean (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Awareness of role | Pre | 36% | 51% | 13% | 2 (0.6653) |

| Post | 82% | 18% | 0% | 3 (0.3902) | ||

| 2 | Confidence in managing challenging situations | Pre | 8% | 46% | 46% | 2 (0.6318) |

| Post | 46% | 54% | 0% | 2 (0.5018) | ||

| 3 | Knowledge of mental health difficulties | Pre | 18% | 62% | 20% | 2 (± 0.6217) |

| Post | 38% | 57% | 5% | 2 (± 0.5748) | ||

| 4 | Confidence in communication | Pre | 25% | 62% | 13% | 2 (0.6103) |

| Post | 67% | 32% | 1% | 3 (0.5047) | ||

| 5 | Confidence in de-escalation | Pre | 7% | 50% | 43% | 2 (0.6076) |

| Post | 47% | 51% | 1% | 2 (0.5277) | ||

A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was conducted to compare scores (before and after training) for 1: awareness of role; 2: confidence in managing challenging situations; 3: knowledge of mental health difficulties; 4: confidence in communication; and 5: confidence in de-escalation.

Free-text survey responses were grouped thematically by the authors. Questionnaire responses were first transcribed and familiarised by the lead author (SD). The second and third authors (CS, LD) independently grouped free-text answers thematically. The lead author (SD) was then brought in to discuss any discrepancies in grouping, so a consensus was reached collectively.

Grouping is presented descriptively. For example, for the question ‘Do you feel prepared for today's session?’, free text answers such as ‘yes’ or ‘the pre-reading gave a good introduction to today's scenarios’ were grouped into the code ‘yes’. Alternatively, free-text codes such as ‘pre-reading was good and thorough, not confident in dealing with the scenarios’ or ‘I have read the pre-reading but find it hard to retain the right words and actions to be used in different situations’ were grouped into the code ‘nervous/not confident’.

Appendices 1–4 (online*) provide a detailed breakdown of free-text answers; Table 2 provides a breakdown of thematically grouped, free-text answers to pre and post questions relating to their self-perceived preparedness for the session, what they hoped to gain from it, what they would take away and make use of and what additional learning they felt would be appropriate.

| Question | Response | Count | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asked before | |||

| Do you feel prepared for today's session? (n=76) | No answer | 11 | 14% |

| No | 14 | 18% | |

| I don't know what to expect | 4 | 5% | |

| Nervous/not confident | 15 | 20% | |

| Somewhat/fairly | 15 | 20% | |

| Yes | 17 | 22% | |

| What are you hoping to gain from this experience? (n=76) | No answer | 5 | 7% |

| Improved confidence in de-escalation | 34 | 45% | |

| Knowledge of techniques to use in de-escalation | 20 | 26% | |

| Improved communication skills | 3 | 4% | |

| Improved knowledge | 14 | 18% | |

| Asked after | |||

| What will you take from today's session? (n=76) | No answer | 2 | 3% |

| Techniques to de-escalate a scenario | 40 | 53% | |

| Realism of the training scenario | 3 | 4% | |

| Confidence to deal with an escalating scenario | 10 | 13% | |

| Knowledge—general improvement | 21 | 28% | |

| Specified techniques to be used (n=40) | Not specified | 5 | 13% |

| Use of body language | 16 | 40% | |

| Positioning in a situation/spatial awareness | 13 | 30% | |

| Communication/voice | 7 | 18% | |

| What other learning would you like in relation to de-escalation (n=76) | No answer | 16 | 21% |

| Scenario-based learning | 17 | 22% | |

| Techniques for aggressive patients | 10 | 13% | |

| Actor-led training | 13 | 17% | |

| Increased knowledge and signposting opportunities around mental illness | 18 | 24% | |

| Peer-led collaboration/teaching/practice experience | 2 | 3% |

Results

The evaluation of the exercise was positive; students reported improvements and valued the inclusion of the exercise.

Predominantly, students self-rated their knowledge as adequate. All questions saw a positive shift in self-assessment after training (Table 1). Questions 1 and 4 saw mean rating move from adequate to good after training.

A Wilcoxon signed-rank test indicated that post-test scores were statistically significantly higher than pre-test scores across all five areas of assessment (Figure 1):

Aside from the 5% (n=4) of students who did not know what to expect from the training and the 14% (n=11) who did not provide an answer, students' feelings were evenly split before training in areas ranging from confidence levels through to not feeling prepared (Table 2). Forty-five per cent (n=34) indicated being more confident in being able to de-escalate a situation, which was the key outcome they wanted to take from the exercise, along with (53%; n=40) techniques on de-escalating a scenario.

After the teaching session, 28% (n=21) reported that they left with greater knowledge and 13% (n=10) felt more confident in dealing with a situation. Fifty-three per cent (n=40) said they would make use of the techniques taught when de-escalating a scenario. Of those, further evaluation showed that body language (40%; n=16) and spatial awareness and positioning (30%; n=13) were the most common techniques that resonated with students to take forward into their clinical practice.

Use of voice (18%; n=7) was the other action pupils stipulated they would use, while five (13%) did not stipulate a specific technique.

Lastly, on exploring what further training would be well received by students, increased knowledge and signposting of where to refer people for mental healthcare (24%; n=18) and scenario-based training (22%; n=17) were rated the highest; however, 21% (n=16) of students did not provide an answer.

Discussion

Communication is fundamental to good practice, as strategies for preventing and reducing conflict have the potential to improve patient safety in healthcare (Panagioti et al, 2019). However, teaching it presents a challenge to both students and teachers (Downs and Hall, 2020).

The teaching exercise intended to make techniques and processes more explicit, enabling inexperienced clinicians to learn from these (Pinnock et al, 2015). The session allowed students to critically engage with their own methods and processes of working, while explicitly considering the theoretical context of such situations within a safe setting.

An overall improvement in knowledge and confidence to manage mental health issues was most evident in the sharp drop in the number who rated themselves or their knowledge as limited. Paramedic students referred to the development of knowledge, practice confidence and non-technical communication skills, and emphasised the value of interdisciplinary learning, as they were able to pick up ‘talking tactics and approaches’ from their peers and from subsequent discussions; there was a particular focus on unconscious mannerisms of which they had previously been unaware.

The improvement in student comfort displays the value of being allowed to practise as opposed to just discuss the soft skills used in clinical practice, while in a safe, controlled environment.

There are potential risks in improper communication while with people in a state of high arousal—statistics showing that assaults on NHS staff are increasing, with 75 000 staff assaulted each year (Wong et al, 2019). While it is not necessarily staff action that precipitates this, the techniques implemented showed students how individuals' actions and manner can alter the dynamic and atmosphere of situations where people are highly stressed.

Traditional methods of treating agitated patients, such as routine restraints and involuntary medication, have been replaced with a much greater emphasis on a noncoercive approaches (Price et al, 2018). Experienced practitioners have found that if such interventions are undertaken with genuine commitment, successful outcomes occur far more often than previously thought possible.

In this new paradigm, a three-step approach is used. First, the patient is verbally engaged; second, a collaborative relationship is established; and, finally, the patient is verbally de-escalated out of the agitated state (Richmond et al, 2012).

Agitation is a behavioural syndrome that may be connected to a range of underlying emotions, the nature of which are exacerbated or precipitated by emergent situations or the input of strangers, such as paramedics, who may be considered a ‘risk’. Associated motor activity is usually repetitive and non–goal directed and may include behaviour such as foot tapping, hand wringing, hair pulling and fiddling with clothes or other objects. Repetitive thoughts are exhibited by vocalisations such as ‘I've got to get out of here. I've got to get out of here.’ Irritability and heightened responsiveness to stimuli may be present but an association between agitation and aggression has not been clearly established.

Qualitative comments expressed how students felt enabled to feel less ‘overwhelmed’ by the presentations and interactions and to approach tutors during the scenario if they experienced barriers to communication with patients.

Given that this was not a formal research study to explore the impact of the training but part of an established teaching programme and concerned the development of skills, there was no requirement for explicit ethical application.

All information collected was used for teaching evaluation. Participation was voluntary in the practical aspect of the teaching exercise, but attendance at the module teaching was mandated as part of the preregistration programme. Students were also informed that providing feedback (or not) would in no way would influence their grade in the clinical course.

Since this evaluation, this teaching exercise will be implemented into future degree programmes and a research project will start to establish if there are differences in learning and its impact on students (e.g. comparing results regarding participant sex, age and experience). This proposed study has undergone full ethical review and received favourable approval, permitting full and potential longitudinal exploration of the effects of such training on the confidence and retention of such in undergraduate students.

Conclusion

The authors note that, after a training exercise such as this one, learners would be expected to report improvements in confidence and understanding. Future work, with greater assessment of the teaching exercise, data collection and statistical analysis across multiple cohorts is anticipated; this has already received ethical approval.

While it is not possible at this stage to definitively measure the impact of the teaching on practice or draw firm conclusions for education providers, the exercise does evidence individual impact and enjoyment, and the authors hope it may lead others to consider the use of scenario-based learning for such skills.

The flexible educational method has the potential to address pressing contemporary challenges in healthcare, such as increasing staff awareness and safety, and consideration of the reduced length and quality of life for people with co-occurring physical and mental health issues.