Patient assessment informs clinicians of the essential data required to produce effective clinical decisions. Failure to identify or understand clinical signs, which should be recognised through accurate history taking, inevitably leads to issues such as: misdiagnosis, the incorrect treatment pathways being followed, and detrimental patient outcomes. Traditional models of ambulance practice predominantly focused on the resuscitation and rapid transport of critical patients, with assessment tools such as primary and secondary survey serving the industry well. Today the expectations on pre-hospital care provision are far greater. A more diverse and complex range of patient complaints are now common occurrence to the paramedic, yet the existing assessment tools and guidelines for practice continue to exclusively address the needs of the ‘traditional ambulance patient’.

Setting the scene

Records of battlefield first aid can be evidenced on Grecian pottery from as early as 500 BC, demonstrating early records of ambulances in alignment with military activities (Pearn, 1994). With global industrial advancements, in particular the introduction of mechanised transport, it was not long before the merits of a service designed for the hostility of war was found to have civilian applications (Haller, 1990). Since this time, great advances have been made in pre-hospital care, with the advancement curve scaling significantly in the last 20 years (Ball, 2005). The modern ambulance serves as a concise mobile resuscitation room or intensive care bay, with a paramedic trained to deliver a rapidly increasing range of interventions for patients. Although the benefits to patients experiencing major trauma or life-threatened injury or illness is unquestionable, industry statistics fail to represent these ‘traditional ambulance patients’ as major stakeholders for ambulance service provisions (Callaham, 1997; Squires and Mason 2004; Lowthian et al, 2011). Meanwhile, everything from vehicle and equipment design, pharmaceuticals, protocols for practice, and even training continue to maintain a focus upon the critically ill or imminently life-threatened patient. This focus is not reflective of the changing face of the modern ambulance patient and the diverse demographic of modern ambulance work (Richards and Farrall, 1999; Silvestri et al, 2002). Locally, ambulance statistics report that 53% of all ambulance calls are considered non-urgent from outset and that another 10% of these patients remain at home (SA Ambulance Annual Report 2009–2010). Of the remaining 37% receiving an emergency dispatch, a reduced fraction of these remain prioritised as a life-threatening emergency once assessed by paramedic crews. Those interviewed in this study estimated the figure of critically ill patient encounters at approximately 5–7% of ambulance work (SA Ambulance Annual Report 2009–2010).

Another notable feature is that ambulance response times continue to represent a key indicator for measuring ambulance performance; however, with the changing nature of patient presentations it is questioned whether measuring how quickly an ambulance arrives at a patient's door is in fact a suitable evaluation tool (Fritz and Wainner, 2001; McIntyre, 2003).

Clinical assessment skills are a feature applicable to every patient that a paramedic encounters. The current recognised assessment tools or methods such as ‘primary and secondary surveys’ serve as filters for decisions regarding whether a patient is critically ill or not. Further pre-hospital investigations remain unstandardised, unresearched, and unvalidated. With so much hinging upon the paramedics' assessment skills, opening the dialogue on the subject is considered to be long overdue (Sackett and Haynes, 2002).

The Delphi Method

With a paucity of existing literature supporting contemporary approaches to paramedic assessment skills (MacFarlane, 2003), an approach was required which could offer insight to the complexities of the issue. The Delphi Method pioneered by the RAND corporation in the 1950s (Loo, 2002) was considered a tool worthy for such an approach. A signature characteristic of the Delphi Method is the independent interviews of recognised experts, completely isolated of each other (Garavalia and Gredler, 2004). Transcripts of their opinions are then circulated to them all, providing opportunity for the comments to be evaluated, reviewed, and areas of consensus acknowledged (Jones and Hunter, 1995). The intrinsic worth of the method features the avoidance of the influence that an individual may have upon the shared opinions of others, removing any individual participant dominance (De Urioste-Stone et al, 2006).

Validity in the researchers' reporting is also achieved through the expert participant's reviews of how their own opinions are being recorded, with capacity for correction and adaptation central to the review process.

Methodology

Those critical of the Delphi Method direct their principal scrutiny at the selection of credible experts (Goodman, 1987). In order to qualify as an expert on paramedic assessment, several filters were created to ensure participants were suitable. The first criterion for expert selection was possessing an ‘established contemporary paramedic practice’. This dictated that the expert be either currently performing paramedic duties, or involved in current reviews of paramedic practice or clinically based training. Secondly, ‘experience’ featured. The expert was required to evidence a minimum of 10 years of practice within their role. It was recognised that throughout this period of service to a role, a candidate may have contributed towards the development of their profession in a number of ways, which may influence how they would respond. For this reason a criteria of ‘employer impartiality’ was included, although it excluded those who may have contributed to the design of current guidelines or protocols. While paramedics practise within a holistic range of health disciplines, much of their work is in isolation, with little feedback regarding the outcomes of their patient encounters or the appropriateness of their practice. In order to avoid an understanding of assessment which was siloed to paramedic practice, experts had to be able to demonstrate experience and knowledge beyond the scope of ambulance work. A ‘wider health knowledge’ criterion was applied. Final criteria were included to balance the participation between ‘gender’ and also even representation of ‘regional/rural and metropolitan’ expert participants.

Approval for this project was obtained from the Flinders University and Southern Adelaide Health, Social and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee and SA Ambulance Service Research Ethics Committee prior to the commencement of research. A letter was mailed to employers of prospective participants explaining the research and requesting consent for participation and support. After receiving this consent, potential participants were contacted individually and an introduction letter and consent form was sent. An introductory phone call was used to gauge participant interest, followed by a formal request in writing. This ensured all participants selected were consenting. It was made clear from the outset that participants were free to withdraw their support and participation from the project at any time of their choosing and for any reason they considered appropriate.

The number of experts deemed as an effective sample reflected multiple considerations. Firstly, the intense and significant volumes of data collected in transcript from each qualitative interview dictated logistical constraints of maintaining a manageable project size (Patton, 2002). Secondly, discussions with several sources including local industry managers, human resource administrators and paramedic academic educators identified only 12 candidate experts fitting the selection criteria, with criteria four proving the most exclusive of the expert profile conditions. Eight of the 12 persons approached agreed to participate in the project.

A total of eight experts were selected for this project. Of the selected experts:

Expert interviews were completed individually in order to preserve the anonymity of the participants. These were conducted at locations and times deemed suitable by the participant, and interviews ranged from between 60 minutes to 180 minutes in length. Audio taping of the dialogue and hand written notes were recorded during the interviews following the consent of all participants. Open ended questions served to generate discussions around a range of themes gleaned from the literature searches (Patton, 2002). The themes for discussion were: paramedic role, process of care, patients, types of patients encountered (and frequency) assessments performed, and recognition of evidence base for practice. The initial expert interview considered a ‘brainstorming exercise’ was followed by an open coding technique (Patton, 2002). From this exercise the data collected was classified into a range of major and minor themes. Following recommendations of Miles and Huberman (1984), codes were assigned.

Results

Although this study targeted paramedic assessment, it became evident that it was difficult to examine this subject in isolation. Asking a simple question such as, ‘how well do paramedics assess the patients they attend’ may initially appear straight forward; however, without any existing measure of assessment performance, coupled with a much divided range of opinions about assessment requirements, the debate became involved. Findings from the study are presented in the following headings representing the emerging consensus themes of the expert responses:

Paramedic role

Distinguishing it from all other professions, the environment in which a paramedic performs their functions was considered the most significant feature of the role. While boundaries for practice were less clear and considered likely to change, experts positioned the role of the paramedic clearly into the pre-hospital and primary care setting. Linked intrinsically with the role was the ambulance vehicle itself, with any suggestions of clinic or department-based functions considered incongruent with a paramedics professional identity. Despite the greater array of diagnostic testing equipment and treatment provisions available elsewhere, it was regarded that working within the confines of a vehicle, or in unpredictable settings with only minimal resources, to be recognisable role features.

Unsurprisingly, emergency response provisions also emerged prominently from the experts; however, the decision regarding what constituted an emergency was considered to be left to the discretion of others, principally patients themselves. Experts also conceded that non-emergency responses must be acknowledged as part of the paramedic role, despite ambulance resources not being geared for these patients. The participants also identified a division of opinions within the workforce between those embracing the non-emergency workload, and a much larger percentage who considered this work to be below them and a consequence of insufficient transport service provisions. Feelings of being under-utilised within their clinical capacity were clearly expressed.

Experts believed there to be few new patient conditions encountered, but rather a significant change in the expectations of the paramedic. Participants advised that patients that may have previously been considered to be fit to stay at home following their ‘emergency assessment’ resulting in unremarkable findings, are now much more likely to be conveyed to hospital due to an awareness of the limitations of the assessment tools being used. Experts suggested that it could be debated whether their peers who regularly left patients at home were either confident or reckless. Experts considered paramedics were prepared for the same non-emergency patient encounter they may have met years prior. The act of leaving the patient at home with some basic health care advice now has the paramedic asking themselves about their capacity to perform this anymore. With regard to the perceived expectations of the role, one expert stated that they were often required to offer:

‘advice about taking their tablets without the training of a pharmacist, advice about resting an injured limb without the authority of a physiotherapist, and coordinating a family member to keep an eye on the patient without being a social worker.’

The paramedic process of care

The expert participants reviewed the activities linked with their roles and the sequence of care they followed. The results partially mimicked features of the nursing process, with several additional steps linked specifically with a paramedic's role. Most notable are the recognised stages happening prior to and following the patient encounter, and the recognition of important logistical considerations besides the immediate patient needs. Akin to the chronological features of the nursing process, each subsequent step in the process influences the next (Varcoe, 1996). Linking with the distinctive environment in which paramedics function was the need to prepare before the patient encounter. The point of dispatch marked the commencement of the paramedics' care, with considerations of safety, logistics, additional allied service availability, access, and egress all mandating evaluation prior to the patient being encountered. An assessment of the scene followed, with many features evaluated for clues that may have contributed to the patient's illness, and features that may hamper care delivery such as patient extrication. All experts cited the importance of evaluating a ‘mechanism of injury’ as being an assessment priority. Linking with the critically ill patient encounter, the experts identified the important stage of the first impression of the patient. Features identified at this stage could change the course of the process of care and were associated with a decision to either ‘stay and play’ or ‘load and go’, a catch phrase of the industry.

Several of the next stages in the paramedic process were more consistent with other disciplines. History taking and examination represented the key components of patient assessment prior to the collected data being evaluated and a clinical decision arrived at. Only when all prior steps had been satisfied did the experts endorse the stage of delivering treatments to patients, but in doing so with a decree for an immediate repeat of patient assessment in order to evaluate effectiveness of interventions. Decisions regarding transportation followed. The practicalities of getting a patient into and out of an ambulance, where to take the patient, how hastily they needed to get there, or even whether there was a more favourable care pathway available to the patient, all contributed to this stage of the process. The final stages of the process identified related to the exchanging of care responsibility during the handover process, followed by an informal reflective process between paramedics where the job is evaluated. Table 1 highlights the stages in the paramedic process.

|

|

Paramedic patients

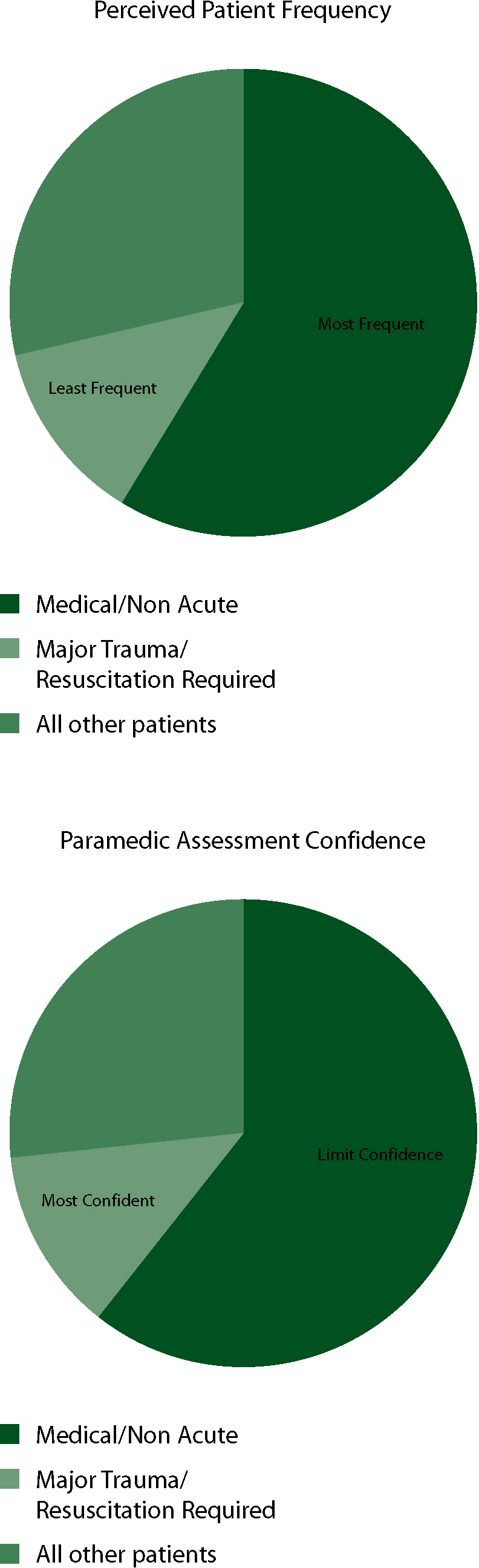

The expert consensus was achieved regarding a range of areas relating to the patients encountered. Alongside their ability to follow their process of care confidently, they rated their peers upon levels of assessment understanding as well as confidence with each of the different patient groups encountered. All experts perceived that the most common patients encountered to be those with general medical complaints which were either chronic or not imminently life-threatening upon presentation. Expert panel members positioned major trauma with imminent threat of life as the least common patient presentation. Participants highlighted obstetric patients to represent the patient group which paramedics manage with least confidence and knowledge, with chronic and non-acute medical complaints to be listed next lowest. Figure 1 shows the percentages of perceived paramedic frequency and paramedic assessment confidence when dealing with paramedic patients.

Assessment

The importance of patient assessment was widely agreed among all participants. With no recognised ‘right way’ of assessing patients, it was viewed that this process was very unique to each paramedic, with most having a ‘style’ they personally used. It was also implied that throughout the industry there existed a great range in the skill level of paramedics in terms of their approaches to patient assessment. With a large volume of the assessment process seemingly linked with communication, it was claimed that “some are great operators, some not so good” which implied that some paramedics were certainly more skilled than others when it came to collecting information from patients.

The decision-making process regarding patient assessment was a feature of all participant discussions. Although there were areas of investigation that were considered generic to all patients encountered by paramedics (e.g. history and allergies), knowing when to employ a range of other investigations was challenging. Even the universally accepted Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) was presented as an expert concern. It was suggested that although the tool featured ‘distinctive neurological domains (eyes, motor and voice)’, the understanding of the clinical relevance of the sub items of the assessment scoring was not profoundly understood by many paramedics. This was despite them being able to effectively compile an accurate score. The dialogue about the assessment of specific patient groups witnessed a return of focus, which was directed towards the clinical practice guidelines and protocols. It was identified that many medical complaints not provided for in a paramedic's list of potential treatments, received extremely limited assessment. A notable group discussed were patients with abdominal pain or gastrointestinal issues. It was suggested that these were still initially assessed as potential chest pain in order to establish that an ischaemic chest pain guideline has been excluded, and if satisfied, the complaint was of a gastrointestinal nature, a handful of generic observations were collected before the patient was taken to hospital. It was a customary belief that there is little that could be done for these pre-hospital patients, so there was ‘little need to investigate thoroughly.’ For many patients' conditions that do not directly articulate with a practice guideline, assessments performed are limited. Patient assessment is regarded as the most influential element in making a clinical decision that prompts paramedic treatment, yet it is still viewed by the experts as being non-standard and inconsistently performed. Of the detrimental patient outcomes resulting from paramedic actions discussed, many of them related to misdiagnosis. At the centre of the misdiagnoses was a tunnel-visioned approach, whereby patients presenting with a set of symptoms were forced to fit into criteria in order to receive intervention under a particular guideline. One paramedic participant reflecting upon the potential for wrongly assigning a particular practice guideline added, ‘when the only tool you have is a hammer, everything begins to look a lot like a nail.’

Discussion

Readily extrapolated from the results is the major component that assessment skills play in the paramedic job description. An evolving profession with an ever increasing level of responsibility to more diverse patients still places assessment skills core to their professional activities. The paramedic process defined by the experts readily quantifies this, with the stages of: dispatch considerations, scene assessment, first impressions, patient history, patient examination, re-evaluation and transport considerations, all representing assessment items. The guidelines and protocol tools used by paramedics to guide their process of care were viewed to be narrowly focused on the execution of treatments and specifically the treatments of critically ill patients. It is apparent that these are currently unsatisfactory to guide the breadth of a paramedic's scope of practice, and particularly constrained the assessment of many patients they encounter. With guidelines and protocols clearly unmatched with patient case presentations, it would be prudent for a review which considers actual case mix statistics. This feature is supported by Kilner (2004) who regards the rigorous investment by ambulance services into resuscitation misplaced.

An alarming consequence of the manner in which guidelines and protocols are currently used suggests there may be merit in a greater patient centric approach to practice. A ‘patient down’ approach permitting a much broader scope of illnesses, as opposed to the current isolated condition or not, currently used by paramedics may benefit pre-hospital outcomes. With many components additionally delivering a clinical skill or drug, it seems timely to invest time into alternative measures of paramedic performance. An emergency department feedback loop which informs all diagnoses and outcomes of the patients conveyed offers much potential merit to a paramedic's practice and outcome measurement.

Conclusions

This study set out to specifically explore the topic of paramedic assessment. What it has served to identify were the breadth of the issue. Findings have opened up the research dialogue in a range of areas new to ambulance services. Because assessment is indelibly placed within the role, representing the majority of all activities within the paramedic process of care, it surely warrants a position on the list of pre-hospital research agendas. The alarming feature of the disparity between the investment in resources, training and clinician confidence when comparing the ‘traditional ambulance patient’ and those whom are the major industry stakeholders should also prioritise assessment on any agenda.