The World Health Organization (WHO) (2006) describes that overweight and obesity are due to abnormal or excessive accumulation of fat (adipose tissue) that may impair health. Obesity is often due to a combination of a less active lifestyle and alterations of eating patterns over time. Some people are more susceptible to weight gain due to medication, or for genetic reasons. However, the fundamental cause of obesity is consuming more calories than are expended. It is important for patients, and staff, to achieve and maintain a healthy weight.

McCormick et al (2007) note: ‘Obesity imposes a significant human burden of morbidity, mortality, social exclusion and discrimination.’ This ranges from its effects on a person's health to their physical management due to their size. The psychological damage caused by overweight and obesity is a huge health burden, and the consequences of obesity can range from lowered self-esteem to clinical depression (The Health Select Committee (HSC), 2004).

Overweight and obesity in adults has trebled over the past 25 years (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2006).

The World Health Organization (WHO) (2009) describes obesity as being one of the world's most significant health problems. According to an article entitled Obesity and Overweight, WHO claim: ’Obesity has reached epidemic proportions globally, with more than 1 billion adults overweight—at least 300 million of them clinically obese’ (WHO, 2010).

Defining obesity

Various methods can be used to determine excess adipose tissue, in particular, Body Mass Index (BMI), waist measurement and waist-to-hip ratio.

BMI

BMI is a mathematical calculation that gives an index of weight, which is measured in kilograms divided by the square of a person's height in metres (kg/m2) (NICE, 2006; WHO, 2006). As BMI is measurable, and well supported by mortality and health statistics, it is frequently used in population studies.

A person's BMI helps to classify whether or not an adult is underweight, overweight or obese. BMI classification is accepted internationally, but should be interpreted with caution, as it does not measure adiposity (body fat); nor does it take genetic history, gender, age or race into consideration. Allowances should be made for people with a muscular frame with no comorbidities (NICE, 2006), and for pregnant or lactating women.

Online calculators and charts (see Further Information) calculate BMI and find the ‘ideal weight’ range. Obesity is considered to be when the BMI is equal to, or greater than, 30 kg/m2 (Table 1). When a person's BMI is over 40 kg/m2, this is termed ‘morbidly obese’ or ‘obesity III’, with 0.9% of men and 2.6% of women being within this category (NICE, 2006). A person's BMI increases amongst middle-aged and elderly people, who are at the greatest risk of health complications (WHO, 2010).

| Classification | BMI (kg/m2) | Risk of co-morbidities |

|---|---|---|

| Underweight | <18.5 | Low (but risk of other clinical problems increased |

| Normal range | 18.5–24.9 | Average Overweight 25–29.9 Mildly incresed |

| Obese | >30 | |

| Class I | 30–34.9 | Moderate |

| Class II | 35–39.9 | Severe |

| Class III severe (morbid obesity, severe obesity or bariatric | >40 | Very severe |

Waist circumference

Central adiposity (abdominal fat) is measured using a person's waist circumference. A ‘raised waist circumference’ is one equal to, or greater than, 102 cm (40 inches) in men or 88 cm (35 inches) in women. For men, a waist circumference of less than 94 cm is a low risk, 94–102 cm is a high risk and more than 102 cm is a very high risk. For women, waist circumference of less than 80 cm is a low risk, 80–88 cm is a high risk and more than 88 cm is a very high risk.

Waist circumference is used in tandem with a person's BMI to assess the risk in people whose BMI is below 35 kg/m2 (Table 2). In 2004, approximately 31% of men and 41% of women were classified as having a raised waist circumference (NICE, 2006).

| BMI Classification | Waist Circumference | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | Very high | |

| Overweight | No increased risk | Increased risk | High risk |

| Obesity I | Increased risk | High risk | Very high risk |

Waist-to-hip ratio

The waist-to-hip ratio (waist circumference divided by the hip circumference) measures the central distribution of fat (intra-abdominal fat) in the body. If this is out of proportion to the total body fat, the likelihood of health risks increases. A ratio of 1.0 or more in men, or 0.85 or more in women, indicates too much central weight (NHS Choices, 2009). The Department of Health (2008) estimated approximately 34% of men and 44% of women had a raised waist-to-hip ratio.

Other factors

Clinicians use additional factors to assess an individual's risk, including family history, level of physical activity, smoking and dietary habits. Bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) estimates body fat by measuring the flow of a harmless electrical current through the body. The more fat a person has, the harder it is for electricity to flow.

Bariatric

The word bariatric arises from the Greek root ‘baros’, meaning large or heavy. ‘Bariatrics’ is the management of extreme obesity and its related diseases. Patients are considered ‘bariatric’ when they have one, or more, of the following factors:

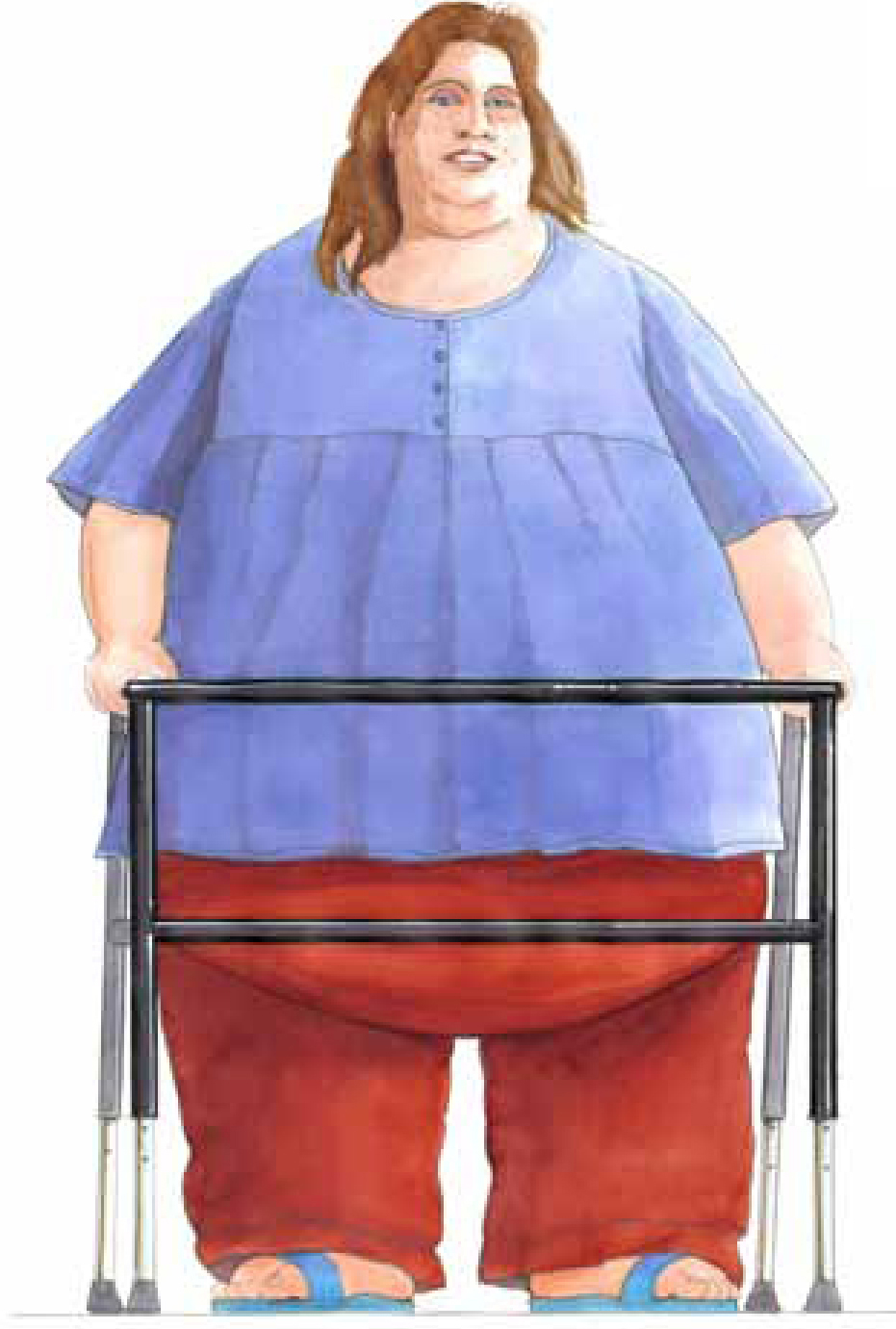

Other accepted definitions of bariatric include being overweight by more than 100–200 lbs (45.36–90.72 kg) or having a body weight greater then 300 lbs (136.1 kg) (Hahler, 2002). The body shape and weight distribution of a person who is clinically described as bariatric is either:

NHS Choices (2009) recommend ‘apple-shaped’ people should make lifestyle changes to increase physical activity and improve their diet.

Effect on health

Carrying excess weight will eventually affect weight-bearing joints, particularly the knees, hips and lower spine, causing osteoarthritis and other musculoskeletal disorders.

Adipose tissue is an endocrine organ and adiposity (obesity) stimulates the secretion of insulin, which can cause insulin-resistance leading to type 2 diabetes. Obesity is also linked to circulatory problems, such as heart failure, and high cholesterol. WHO (2010) describes that the likelihood of type 2 diabetes and hypertension rises steeply with increasing body fatness; approximately 85% of people with diabetes are type 2, and 90% of these are obese or overweight.

Other medical problems related to obesity include birth defects, miscarriages, sleep apnoea, gallstones, fatty liver disease, stress incontinence, asthma and other respiratory difficulties, some cancers in men (oesophageal, colorectal, liver, pancreatic, lung, prostate, kidney, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, multiple myeloma and leukaemia) and cancers in women (breast, colorectal, gallbladder, pancreatic, lung, uterine, cervical, ovarian, kidney, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and multiple myeloma).

When a person is only slightly overweight, health problems can begin. The likelihood of serious problems related to risks stemming from diet-related chronic diseases rises as a person moves from being overweight to obese. Around 34 000 deaths annually are attributable to obesity, one third of which occur before retirement age (McCormick et al, 2007). Deaths caused by obesity, on average, reduce life expectancy by nine years (NHS Choices, 2010). There can be severe restrictions on a person's level of mobility and their ability to manage daily living, thus reducing quality of life and psychological and social difficulties.

Obese patients impose considerable economic burdens to society including welfare benefits (McCormick et al, 2007). HSC (2004) estimated the cost of obesity in England is between £3.3 and £3.7 billion per year. The HSC’s estimate includes £49 million for treating obesity, £1.1 billion for treating the consequences of obesity, and indirect costs of £1.1 billion for premature death and £1.45 billion for sickness absence. The cost of obesity plus overweight is estimated between £6.6 and £7.4 billion per year.

Managing bariatrics

The subject of obesity receives considerable attention due to the health issues that arise for patients. The number of obese people needing hospital treatment has more than trebled, and as Britons get bigger, moving the super obese to and from hospital has become a challenge. This is traumatic for patients, and dangerous for health staff.

The bariatric patient has the right to be treated with the same comfort, dignity, respect, and privacy as other patients. Bariatric patients often need assistance with ambulation, transfers and repositioning themselves in an ambulance or on a trolley. They may not be able to tolerate lying flat on their backs, so the head of the stretcher or trolley may need elevating. This is not only due to their size, but also to common associated heart and respiratory conditions. This new patient group has led to the development of an ambulance that is capable of moving people who weigh up to 70 stone (444.5 kg)—the bariatric, or ‘supersize’, ambulance (BBC).

Admission to hospital

Many patients have pre-admission assessments, e.g. antenatal patients or planned surgery. An assessment should identify the patient's weight, height, BMI, weight distribution/body type and girth. Mobility and daily living can be affected by obesity. The patient's level of mobility and level of abilities should therefore be recorded. This will enable staff to identify if any moving and handling activity requires guidance and/or assistance as paramedics may need to provide assistance to enable patients to transfer, stand, or walk.

When planning transportation, the size and weight of a patient should be provided to the ambulance personnel, as not all ambulances are designed to transport bariatric patients. However, some ambulances have seats that can be folded up to create more space. The need for any heavy duty or specialist equipment can also be identified so that this can be available when transporting bariatric patients.

As an emergency admission of a bariatric patient may necessitate the closure of a bed space, the accident unit should be warned if any specialist or heavy-duty equipment is needed. Health and Safety Executive (HSE) (2007) note an area may have adequate clearance for everyday use, but may not be sufficient for bariatric patients whose movement may be impeded. Sufficient staff will be needed for all moving and handling procedures and additional staff may be required on shifts. Many hospitals have evolved their own policies on caring for Bariatric patients including having a list of transferable equipment available for the care of bariatric patients.

The growing numbers of obese patients prompted University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust to order super-size facilities such as bed spaces and examination rooms for heavier patients, as well as beds, mattresses and hoists for those weighing at least 160 kg at its new Queen Elizabeth hospital, which opened in 2010 (Campbell, 2013). The higher safe working limits mean each ward has a heavy-duty commode for patients weighing up to 318 kg, a ceiling track hoist with a weight limit of 450 kg and a wide armchair that can hold someone up to 260 kg, though three others can withstand 445 kg (Campbell, 2013).

Risk assessment and training

The HSE (2007) have outlined five generic risk areas relating to the moving of bariatric patients, namely: patient factors (size and weight); building (or vehicle) space and design; furniture and equipment (manual handling and clinical); communication; and organisational/staff issues. These risk-factors need to be considered when moving a bariatric patient.

When a Bariatric patient is lifted, moved or transported, a comprehensive risk-assessment must be undertaken and documented. Ergonomic risk-factors must be assessed, e.g. the working-load limit of any fixed or moveable equipment that is to be used. Even lifting a limb, which is often necessary to assist a transfer, can exceed an acceptable weight limit. For example, a leg is approximately 16% of a person's total body weight and spinal loading should be limited to forces below 3400 N, which is about 35l bs (15.88 kg) (Muir & Archer-Heese, 2009). The weight of a leg of a 350-pound patient would be 62lbs (28.12kg). Muir & Archer-Heese (2009) also note that lifting such a leg far exceeds a safe lifting load, therefore a mechanical lift device and limb sling should be used while performing an activity, such as this, to offset excessive loading.

Reaching across a bariatric patient is another potentially dangerous activity that can place a paramedic outside of safe working and reaching ranges. Safe reaching occurs when (a) one's elbows are close to one's sides, (b) reaching is limited to a 24 inch (60.96cm) radius with the elbow as a pivot point, and (c) the reach is not over the shoulder height (Muir and Archer-Heese, 2009).

Paramedic staff must have adequate training to reduce the risk of musculoskeletal injuries. Staff must feel confident and competent to undertake patient handling within their roles. If they identify any ergonomic, manual handling or tissue viability concerns these must be reported immediately and documented.

Conclusions

Obesity can cause a substantial impairment of function with a resultant disability. Diseases associated with overweight and obesity include coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, osteoarthritis and some cancers. Assessment of overweight and obesity includes the evaluation of BMI, waist circumference, waist-hip ratio, and overall medical risk.

It is important to follow moving and handling guidelines, whilst realising that a patient's level of function and mobility can change due to medical issues. All staff need to be aware of the problems that can arise when over-sized patients are admitted to hospital, seen at clinic or managed in the community. Bariatric equipment may be needed and a patient's size and weight must be able to be accommodated in the equipment that has been supplied.

However, more than half of the adult population is overweight or obese. A considerable number will need physical help and support during any transfer. There is no simple solution to safe movement and handling and this needs to be tailored to individual patients.