The Five Year Forward View (NHS England, 2014) argues that the sustainability of the NHS and economic prosperity depends on improving prevention and public health. As smoking is the leading preventable cause of illness and premature death in the UK (NHS England, 2014; Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), 2017), Public Health England (PHE) (2014) has responded by making smoking cessation a health promotion priority, aiming for a ‘smoke-free’ NHS by 2020 (NHS England, 2017).

The negative impact and cost of smoking in terms of both public health and the economy almost go without saying (Box 1). Smoking cessation interventions are one of the most cost-effective treatments, saving £1000 per life year gained after quitting (National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training (NCSCT), 2017). In 2006, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) produced guidelines on opportunistic brief interventions for smoking cessation (NICE, 2006). However, the role of the paramedic was not considered in the original report. This meant that the potential impact and scope of influence paramedics may have had in this important area of health promotion was not discussed or realised for more than 10 years. Subsequent guidelines have recognised that paramedics have a role to play in smoking cessation (NICE, 2018) but they contain little practical advice, and no realistic blueprint for quality improvement.

This article seeks to address this perceived deficit and provide paramedics and services with a simple model that will lead to quality improvement in terms of patient wellbeing, paramedic job satisfaction and public health.

Objective

Train paramedics to give a brief intervention (very brief advice (VBA)) on smoking cessation using the three As (AAAs). The AAAs is an opportunistic brief intervention tool given to all smokers, regardless of whether they are motivated to quit, based on a seminal systematic review by Aveyard et al (2011), who found that physicians were more effective offering assistance to all smokers, rather than only to those who expressed an interest, resulting in almost twice as many quit attempts (Table 1).

| ASK |

|

| ADVISE |

|

| ACT |

|

The AAAs guide referrals to local NHS Stop Smoking Services where patients will receive specialist care from a stop smoking practitioner, and obtain nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and/or medications to increase their chances of quitting (Aveyard et al, 2011).

The College of Paramedics (2017) has identified that paramedics should provide health promotion using practical skills including brief intervention; however, no specific interventions have been suggested to effectively teach this. The AAAs provide structure and numerous benefits for the ambulance service compared with other smoking cessation treatments (Box 2).

Supporting evidence

With the patient's consent, under the ‘Act’ step in AAAs, they are referred to the local stop smoking services where they receive specialist care including NRT and/or medications to increase the likelihood of quitting as demonstrated by Aveyard et al (2011). The chances of quitting were 217% higher with the offer of support compared with no support at all, and 68% greater with medication.

A systematic review by Lancaster and Stead (2017) shared similar results supporting that smoking cessation practitioners increase the likelihood of long-term abstinence. The decision to refer patients to specialist stop smoking practitioners, is substantiated by 2016–2017 statistics (NHS Digital, 2017a), which found that most quit attempts (248 847) were made through ‘one-to-one’ support from a stop smoking practitioner compared with other intervention types like telephone support (10 593). Additionally, further reasoning behind suggesting pharmacotherapy in the ‘Advise’ step is provided by NHS Digital (2017a) statistics from 2016–2017 showing over five times as many quit attempts using NRT than without.

The AAAs is a low-intensity intervention that takes ‘30 seconds to save a life’ (Chambers, 2011) and requires no additional materials or equipment. A randomised controlled trial by Hajek et al (2002) found no evidence that additional written material or carbon monoxide (CO) measurements showed any benefit over brief advice. However, Lancaster and Stead (2005) challenged this conclusion arguing that additional materials added benefit to consultations (95% confidence interval 1.05–1.39). However, the authors overlooked that the results were only just statistically significant with a broad confidence interval, suggesting imprecise results that should have been interpreted with caution.

A more recent review by the same authors concluded however that various aids did not enhance the effectiveness of physician advice. It found no significant differences between 10 studies where the intervention incorporated additional aids (95% CI 1.46–2.01) including CO recordings and leaflets, compared with 17 studies where such aids were not used (95% CI 1.56–2.04) (Stead et al, 2013). With overlapping confidence intervals between the two subgroups of studies, this demonstrates that no significant differences were found, increasing the precision of the results.

Rice et al (2017) also found insufficient evidence to say that incorporating physiological feedback, as an adjunct to the intervention was more effective compared to without it. Based on insufficient evidence to support the effectiveness of additional materials and to ensure it remains cost-effective, these will not be included in the intervention.

Quality improvement process

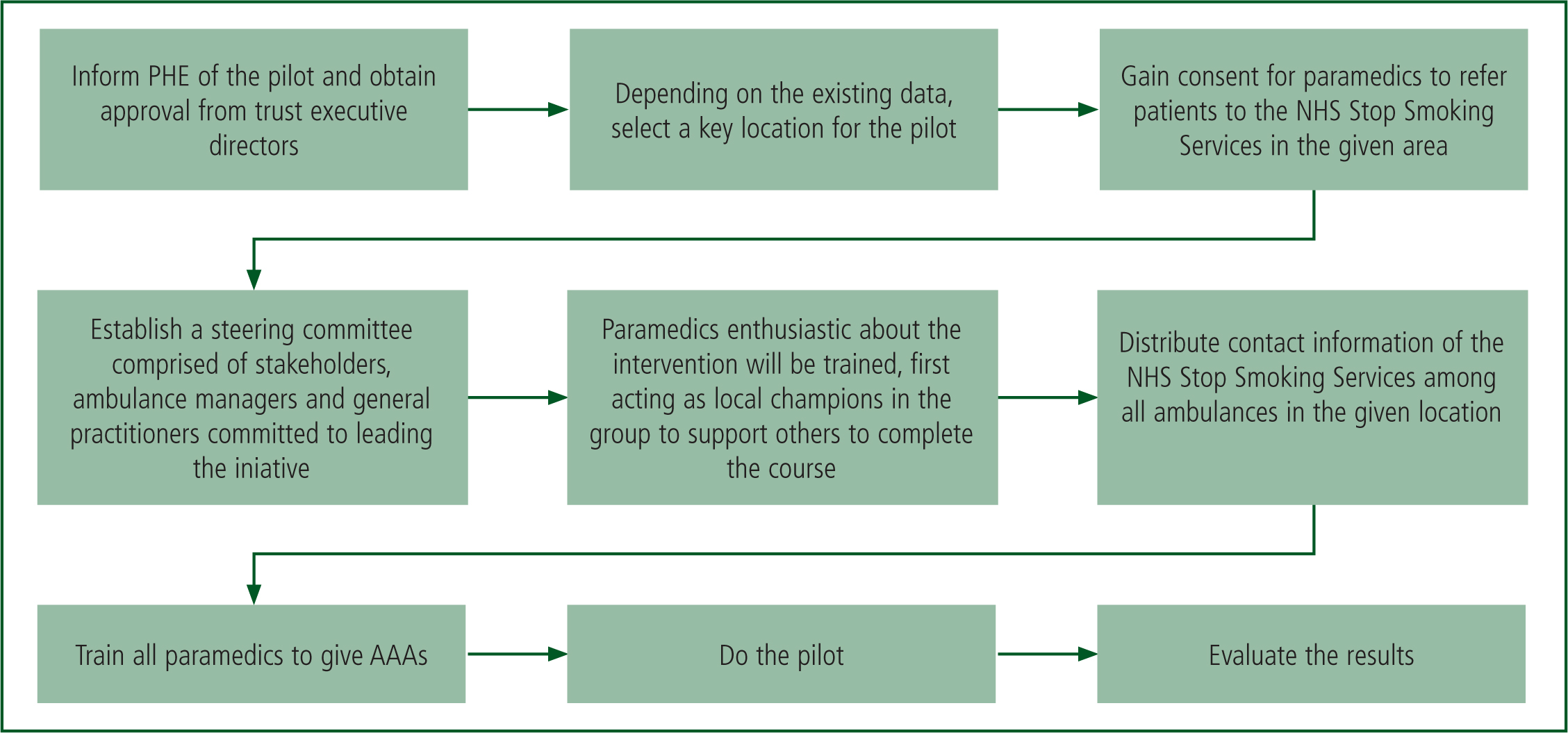

To achieve the NICE (2015) quality standards for service improvement, the model for improvement (NHS Improvement, 2017) will be used consisting of three fundamental questions and a Plan Do Study Act (PDSA) cycle (Figure 1) to trial the intervention as a pilot; assess its impact; and draw in stakeholder interests, before wholesale implementation.

The three fundamental questions

What are we trying to accomplish?

The primary outcome is to achieve paramedic referrals to stop smoking services to increase quit rates. This can be achieved by:

How will we know that a change is an improvement?

NHS Digital (2017) produces quarterly statistics on:

By dividing the number of people who set a quit date by the number of patients who were abstinent at 4-week follow-up, the quit rate percentage is calculated (NICE, 2018). Evaluating the impact of paramedic referral could be challenging as NHS Digital does not currently include information on where referrals originate from. This means that the percentage of referrals made by paramedics or ambulance services compared with other referral pathways cannot be calculated at present. However, it may be possible by looking at pre- and post-intervention Statistical Process Control (SPC) charts to infer whether ambulance referrals have contributed to the percentage quit rates, which would be a validation of the strategy.

What changes can we make that will result in improvement?

| Risks and complexities | Overcoming barriers |

|---|---|

| Harm to patient | There is no risk of harm to patients or compromise to the quality of care provided as only clinically stable patients would be targeted |

| Costs incurred running the course | Although administration costs must be considered, the NCSCT (2017) training is free to all healthcare staff |

| Reduction in available workforce for training | NCSCT training could be incorporated into induction and CPD days preventing impact on operational function |

| Resistant attitudes | The course takes 15 minutes to complete and everyone is rewarded with a certificate after completing the course. It is excellent CPD |

| Impact on service delivery | Only clinically stable patients would be targeted reducing the impact of VBA impacting on critical interventions. |

Evaluation

The key objective of the pilot would be to determine whether the objective was achieved by summative evaluation (The Health Foundation, 2015). This would analyse whether paramedics were able to refer patients to local NHS Stop Smoking Services and give the AAAs.

Quality improvement may be determinable using SPC charts showing whether there is an increase in quit rates since the introduction of paramedics giving AAAs.

For a thorough summative evaluation, the logic model in Appendix 1 may be used to demonstrate how the outcomes are expected to come about. It identifies assumptions to be explored and questions highlighting areas for improvement (University of Wisconsin, 2003) in line with evaluation standards set by the Joint Committee on Education Evaluation (Yarbrough et al, 2011). Examples include:

To ensure all stakeholders remain engaged, the feedback will be shared and they will be invited to contribute additional improvements (NHS Improvement, 2017). To meet NICE (2015) quality standards, for every change that is made, the PDSA will be repeated to see whether the associated change has had an impact on quality.

NICE (2015) also recommends repeating the PDSA periodically until a standard has been reached whereby the improvements are being sustained. Afterwards, the improved PDSA can be applied to other areas allowing for dissemination of the intervention beyond local level.

Conclusion

Very brief advice is an evidence-based, effective and time-efficient way of reducing harm from smoking and improving quality of life for patients, while improving the care delivered by paramedics and saving the NHS money. To determine the effectiveness and practicality of paramedics giving VBA, a pilot study is required with evaluation of the data before wholesale implementation at a service or national level.

Notwithstanding the need for service-level pilot and evaluation, incorporating VBA (specifically the AAAs) into practice will improve patient outcomes and may enhance paramedic job satisfaction.