Biggs and Tang (2007) suggest that feedback is important for students to learn and apply, to therefore progress. Many authors recommend that feedback should be of a suitable quality in order that the student is able to learn from it (Willingham, 2000; Nicol and MacFarlane 2006Biggs and Tang, 2007). Without the ability to learn from feedback, students are doomed to repeat the same or similar errors without comprehension.

A controversial text authored by Allen and Ainley (2007) however, suggests that students receive too much support, and therefore do not learn to develop themselves but are developed by others. However, Allen and Ainley (2007) could be alluding to the use of coaching as against instruction, whereby the student is encouraged to discover their own solutions (facilitated by the tutor) rather than being directly told where they have gone wrong.

In my own teaching, I prefer to use a coaching method as it encourages students to think more effectively about their work, and provides skills that they can use in future assignments and areas of work as suggested (Everson and Henning, 2009).

The national student survey (NSS) suggests that feedback is important to students studying in the UK, and that they would prefer ‘better’ and timelier feedback (University of Worcester, 2009). ‘Better’ however, cannot be defined effectively, as it will have different connotations to each student.

Within the context of paramedic studies, I believe that feedback is not as effective as it could be— specially in terms of the usefulness of the feedback given to the student. This conclusion has been drawn from assignments that have been submitted previously. Some students make similar errors in assignment after assignment.

Obviously, there could be many reason for this, for example, the student may not read the feedback given, they may not understand the information provided, they may not understand how to apply the feedback to other assignments. However, the NSS demonstrates that only 57% of students who took part in the survey believed that the feedback they received was constructive (Higher Education Funding Council for England, 2009). Thus, adding to the argument that current practices may not be providing the information that students require.

Currently, my students are provided with a hand written summary of the marking tutors comments on a standardized form. The form provides a limited space in which to write, and therefore limits the amount of feedback that can be given. The same form is used by any moderators, thus limiting any additional feedback as the majority of the space could be utilised by the initial marker. It is accepted that additional forms could be used, however this is rarely done as the student provides the form, and therefore spares are generally not available. Scripts are annotated by some markers, however, in my experience, annotation is not a routine occurrence across the institution.

Often, the written forms are the only feedback that a student receives. Students who have failed to meet the required standard generally receive a face to face tutorial in order for the tutor to explain further the areas that require work. This service is rarely afforded to students who achieve pass grades, unless they specifically request a tutorial.

Furnborough and Truman’s (2009) research suggests that students who are new to higher education find it more difficult to assess their own progress based upon written feedback. Although Furnborough and Truman’s (2009) research focused upon students who were studying languages at a distance education institution, my students are receiving a similar type of feedback to that discussed by Furnborough and Truman (2009). Therefore, they could also be finding self assessment difficult, suggesting feedback could be refined to assist the student.

Control over feedback

Nicol and MacFarlane (2006) suggest that in order to feel ownership, and therefore respond more effectively, students should have some control over the feedback they recieve. Therefore, suggesting that students should have some facility to choose the way they receive their feedback. It is possible that the students’ requests could link to their respective learning styles, in that they may to prefer to receive feedback in a way they learn most effectively. Therefore, adherence to their preferred method could assist the students’ learning.

There are other ways students can receive feedback on written assignments in addition to written forms, for example: tutor recorded audio files or videos provided by email (Inglis, 1998; Furnborough and Truman, 2009), or face-to-face meetings. Orsmond et al (2005) suggest that students prefer verbal feedback when compared to written, and Ribchester et al (2008) suggest that audio feedback can provide a greater amount of detail and the learner is more likely to engage with the feedback given.

However, recorded audio and video feedback both have limitations, in that the student cannot directly engage with the tutor. In addition, audio files can be very large and therefore take considerable time to upload and download (Merry and Orsmond 2008).

Willingham (1990) does not directly recommend face-to-face meetings with students, however, both he and Ribchester et al (2008) allude to face-to-face contact being beneficial. During a meeting, a student can ask questions to clarify areas of concern, the tutor can rewrite sections, both tutor and student can use verbal inflections to clarify concerns, they can physically point to text and use both verbal and non verbal communications skills to understand each other as suggested by Hargie (2006). This is supported by Jessop (2007) who states that students prefer direct contact and conversation with the tutor.

Chanock (2000) raises the issue of understanding, and highlights that much of what is written can be misinterpreted. I believe that during a face-to-face verbal conversation, less misinterpretation will occur when compared to written communication.

This is supported by Hargie (2006) who suggests that a great deal of understanding stems from body language including eye contact and facial expressions. These discussions lead me to consider that a face to face meeting with the student might be the most effective form of feedback.

It seems strange that there is a wealth of literature regarding how tutors can best support student learning, however there is less literature regarding how feedback is given to students. This could be that feedback is approached as part of the assessment process, which, from experience is generally not tailored to individuals students needs. Thus, the student receives ‘standard’ feedback.

Title and aim of research project

With the above discussion in mind, one logical piece of research would be to consider giving students an element of choice over the format of the feedback they receive. Then, analyse their opinions regarding its usefulness. The research title would be: Are current feedback methods optimal for student understanding and learning?

Thus, the following research will aim to discover what the student preferences are in terms of feedback format, and once received, how useful the feedback was in comparison to the ‘standard’ form which all of my students receive.

Literature review

In order to complete a comprehensive literature review, I used an internet based approach to searching for journals, using search engines such as Academic Search Prermier, CINHAL, and Google Scholar. A paper based approach was also taken using books and journals. A great deal of information was found regarding the concept of feedback, however, I found a limited regarding the format of the feedback.

The vast majority of research agrees that feedback is vital for the learning process, however most papers either allude to feedback being given in a written format (Furnborough and Truman 2008, Plater 2007) or are very non specific (Freestone 2009). A few papers directly discuss the format of feedback (Peters et al undated, Bridge and Appleyard 2008). Jessop (2007) states however, that students wished to have a feedback process that was ‘interactive and dialogical’.

There appears to be more research from Australia than the UK regarding feedback, for example Everson and Henning (2009), which has been used with deference to cultural differences. The bibliography details all of the literature review during this project, research directly used is shown within the reference list. The result of the literature review can be seen in the initial section: ‘identify something that could be improved’.

Methodology

On 15 February 2010, a group of 15 students commenced an FdSc course. The group of students were selected to take part in the study for several reasons. The students had not previously received feedback from this institution; therefore they were unfamiliar with the process ‘usually’ adopted. Their lack of familiarality with higher education and this institution would suggest that they would have no preconceived ideas regarding the usual process at this institution.

It is accepted however, that some of the cohort have undertaken higher education at other institutions, therefore may have a bias towards one form of feedback or another.

The research project was designed to focus upon feedback to written, assignment based assessment.

The students were informed that they would receive what I consider to be standard feedback— the written form, in addition to their chosen method. The students were able to select whatever method they wished, with no constraints. Once the feedback had been given and time allowed for assimilation, the students were then to be asked which method was more beneficial to them. The timescale allocated for feedback to be given and for assimilation was five weeks, between the 29th March 2010, and 26th April 2010.

On the 23 February, I was due to discuss the research with the students, and receive their ideas and requests. The discussion was to be audio taped to ensure accuracy was achieved, and to ensure a record of the discussion could be kept for validation.

However, during a classroom based exercise on the 17 February 2010, one of the students requested to know how they would receive assignment feedback. I discussed the research at that point, and all students agreed to take part. The students were requested to email their preferred method for of feedback to me, so that a record could be kept and accuracy ensured.

It was noted during the discussion, that the students had very few ideas of how they could receive feedback. This has two opposing points of view, the students would not have a preferred method of feedback, therefore potentially allowing them to think more freely about their choices. Conversely, the students have nothing to compare their feedback against, therefore, they could respond positively to what an experienced student may consider to be a poor feedback method.

I made various suggestions to the students, for example: individual tutorial discussions, group tutorial discussions, written feedback, audio feedback and tick box sheets. Upon receiving the students preferred feedback strategy, it became evident that a face–to–face tutorial discussion was almost every student’s choice (fourteen out of fifteen). One student opted to have feedback via email. The students did not all email their preferred choices as requested, therefore I asked them to write their choice on paper and hand it to me, which they did.

Time scales

The project was due to commence on the 23 February 2010, however, it commenced on the 17 February 2010 due to the students requirements. The students submitted their assignments on the 15 March 2010. The standard feedback form was given to the students on the 12 April 2010, and tutorials were booked between the 12 April 2010 and the 28 April 2010. These time scales allowed a further four weeks for the analysis and write up of the project.

Results

Out of the 15 students who were recruited into the research, 13 returned their evaluation sheets. All 13 students completed the form appropriately and completed the first four questions—the fifth being optional. Two students received their feedback tutorials but did not return their forms. I was unable to directly unable to contact the students as the forms were anonymous. All students were asked to ensure they returned their forms, however, this did not happen.

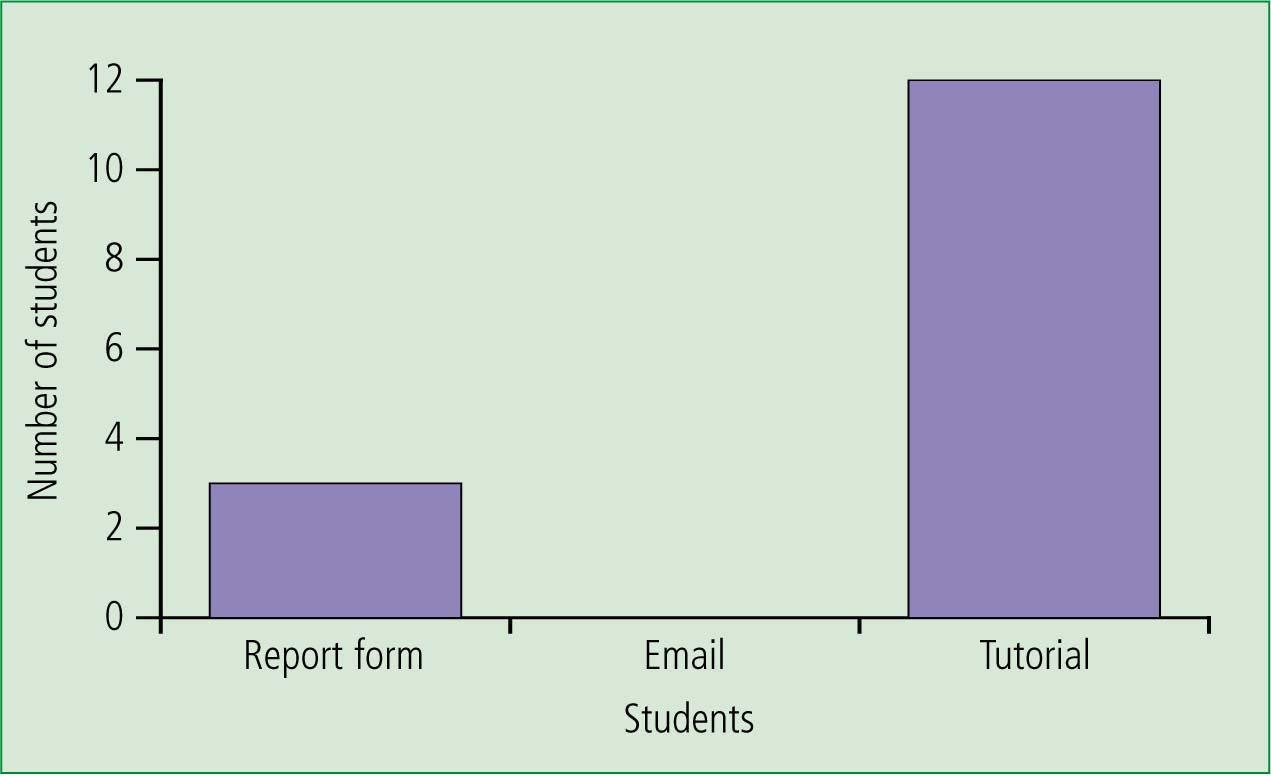

The student who requested email feedback commented that the item report form was more help than the email feedback. Ten students who received tutorial feedback and returned their evaluation forms commented that the tutorial feedback was the most useful, two students commented that the tutorial feedback and the written feedback were valuable together (Figure 1). The standard feedback given to the student contains approximately 300–400 words, the content obviously varies depending upon the assignment, however, I aim to highlight good practice along with areas that require improvement.

In addition, the students suggested that tutorial feedback assisted them in developing

Some students took the opportunity to comment further in the optional section. Comments included the positive nature of their feedback and the desire for further tutorials, suggesting they found the tutorials beneficial.

Discussion

The first face-to-face feedback session occurred on the 8 April 2010 at 10am and lasted for two and a half hours. This was initially worrying as fourteen students had requested a face-to-face meeting, which based on the initial tutorial would require approximately 35 hours of my time. However, all tutorials would not take as long as this one, due to the first student having been unsuccessful with one assignment.

Most tutorials took between three quarters of an hour and an hour using a total of sixteen hours— each student was advised that they had a one hour slot, time keeping was aided by having another student booked directly after the first.

As a result of this study, in future, I would limit each student to a 30 minute time slot (depending on the number of assignments to be discussed) to ensure that the time is used effectively. Consideration also needs to be given to having a strategy for finishing a tutorial with a student who may wish to have more time.

Writing the email for the student who requested this type of feedback was not as time consuming as the tutorial sessions. However, I found that I was struggling to make additional comments to the ones already on the standard form. I found that I had to read through the assignment again in order to make further comments, suggesting that the email should have been written at the time the assignment was marked. However, due to the assignments being marked anonymously this would clearly identify the student, and thus removing their anonymity, leading to potential biased marking.

The institute's policy on assessments requires the marking to be conducted anonymously where possible to avoid bias (University of Worcester 2008). Orsmond et al (2005) suggest that the submission of formative assessments in the form of drafts also reduced the effectiveness of anonymous marking. These students were able to submit a draft of the assignment, potentially leading to loss of anonymity.

Whilst marking, I was very aware that I had read some of the assignments before, and indeed I could identify some of the assignments authors. Thus, leading to the dilemma, ‘Should students be able to submit drafts?’. It could be questioned how the student can be expected to improve their work prior to submitting their summative assessment if they do not submit a draft.

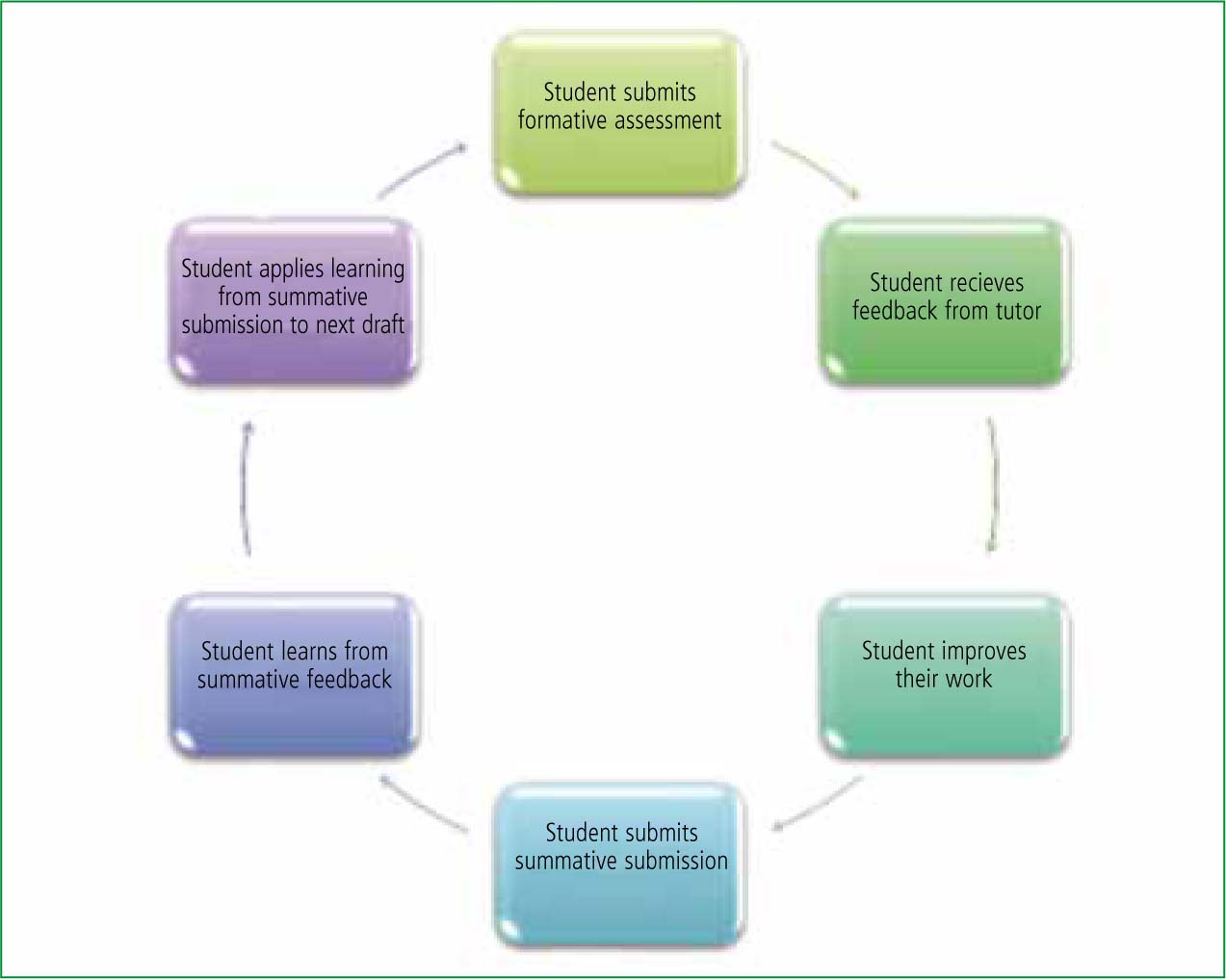

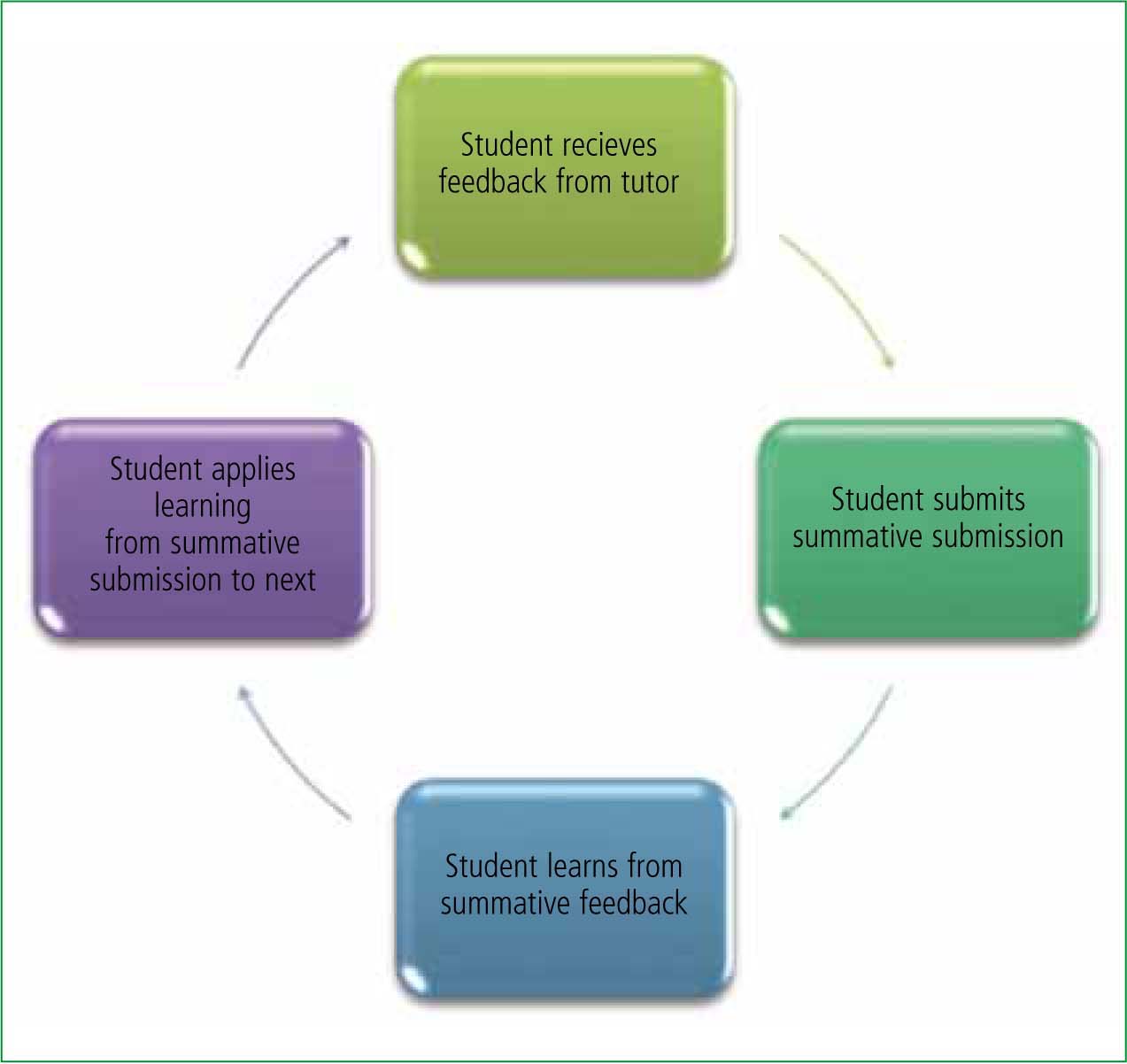

A learning cycle including a formative assessment is illustrated in Figure 2. Without a formative submission, the student is potentially losing a valuable learning experience—this is illustrated in Figure 3. Formative submission is work that is marked and commented upon, but it does not form a part of the grade for a module, summative work is marked and the grade awarded does go towards the qualification being undertaken.

Learning and applying

Consideration has to be given to the fragile step between a student learning from feedback and a student applying learning from summative submission to the next summative assessment (Figure 1). The fragile step is one that is not guaranteed to occur as the student may not be able to apply the knowledge across the assignments. In addition, they may choose to ignore the feedback as they have received their grade and see any further consideration of the assignment to be pointless.

Consideration also needs to be given to whether the loss of anonymity is more detrimental than loss of formative feedback. Jessop (2007) suggests that students prefer not to have their work marked anonymously. I believe that the loss of feedback is more detrimental than loss of anonymity.

I would also give consideration to asking the students to lead the tutorial, which would require them to think about the feedback they received and tailor the subject matter to suit their individual needs. This method would give ownership of the process to the student, and assist with empowering them, as recommended by Biggs and tang (2007).

The results section clearly shows that the majority of the students’ preferred tutorial feedback, potentially due to the quality of feedback than can be delivered verbally compared feedback in a written form. In addition, during the tutorials, all students asked for clarification of points that were raised either in writing or verbally—hence allowing the student seek understanding.

Biggs (2003) stresses the importance of students understanding their feedback and being able to use it. I believe that the students understood their feedback more effectively than if they had received only written feedback. However, a subsequent set of assignment grades may demonstrate if the students used their feedback more effectively than other students who did not receive tutorial feedback. I am hoping that their future assignments will show a decrease in repeated errors and higher grades than would be expected.

Impact of individual tutorials

The impact of individual tutorials upon me was a significant one. I had to allow for fourteen students requiring tutorials of approximately one hour each in order to cover the three assignments allocated to the research, which obviously equated to fourteen hours of tutorials. To achieve these tutorials, I allocated time slots prior to the students’ taught sessions and after taught sessions, extending my working day by an hour on occasions.

Although, some students missed their allocated time slots and therefore had to be rearranged, this took further time from my diary. The tutorials extended from 12 April to 28 April due to my lack of time slots for these tutorials. The time scale taken to complete all of the tutorials was not acceptable, as the students focus had moved from their completed assignments, to the assignments that were in progress.

Timeliness

Norton (2009) discusses the importance of students receiving timely feedback, I do not believe that I achieved timeliness within this study. It is possible that I need to reach a compromize between the timeliness and use of feedback. In addition, when implementing this type of feedback, I would plan further tutorial time prior to creating other commitments. I would also consider using this type of feedback with the first semester modules as a mandatory feedback method, and perhaps consider it as an optional method for second semester onwards, purely due to time constraints.

Conclusion

The students clearly showed a preference for face-to-face tutorial feedback after assignments have been assessed. I believe the students found the tutorial feedback was more useful than pure written feedback. However, consideration needs to be given to the timescales involved in terms of the amount of time required to complete the tutorials, and the timeliness to avoid the students’ focus from changing.

Forward planning could assist with allocation of tutorials, allowing for more rapid feedback.

I would also impose a 30 minute time limit on each tutorial, depending upon the number of assignments to be discussed. Rapid and useful feedback could then assist the student more effectively with their future assignments (Biggs 2003). I will definitely use this method of feedback in the future, potentially as a mandatory feedback tool with first semester students and an additional and optional tool for more advanced students.

In conclusion, I would suggest that my students do not believe the current system of feedback is optimal for their learning.