Pain is recognised as the leading cause of presentation to acute medical services, whether in an Accident and Emergency (A&E) setting or an out-of-hospital setting (De Barardinis et al, 2013; Motov and Nelson, 2016). Optimal management involves the rapid assessment and recognition of the causative agent, with subsequent removal if possible, and appropriate analgesic administration (De Barardinis et al, 2013; Motov and Nelson, 2016). There is substantial evidence to suggest adults with cognitive impairment, caused by degenerative conditions such as dementia, are at a significantly higher risk of suboptimal pain assessment and management in the acute care setting, when compared to adults without cognitive impairment (Hwang et al, 2010; Somes and Donatelli, 2013). Evolving methods in the diagnosis of conditions such as dementia over the past two decades have seen significant variances in their projected incidence (Matthews et al, 2016). However, with up to 849 000 adults living with cognitive impairment in the UK alone the importance of addressing this key area of clinical practice cannot be understated (Luengo-Fernandez et al, 2012). A variety of tools have been developed to assist in detecting the presence of pain in the cognitively impaired adult (Somes and Donatelli, 2013), although minimal literature exists examining their usefulness in an out-of-hospital setting. This paper aims to assess the pain assessment tools most appropriate for use in adults with cognitive impairment as a result of dementia within the out-of-hospital setting.

What is pain, and why assess it?

Defining pain is complex; however, it is generally agreed to be an unpleasant, emotive and personal experience (Briggs, 2010; Steeds, 2013). Pain is generally split into two categories: nociceptive and neuropathic (Briggs, 2010; Steeds, 2013). Nociceptive pain relates to the normal physiological response to pain where a traumatic stimulus causes the release of endogenous chemicals, such as prostaglandin and histamine (Briggs, 2010; Peri, 2011; Steeds, 2013). This leads to the transmission of an electrical impulse to the brain via the nervous system for perception and subsequent reaction (Briggs, 2010; Peri, 2011; Steeds, 2013). Comparatively neuropathic pain is the result of damage or dysfunction of the nervous system (Peri, 2011; Steeds, 2013; Cohen and Mao, 2014). This may occur in the central nervous system as a result of persistent stimulation of the nervous system, despite the removal of the causative agent, or in the peripheral nervous system where damaged interneurons may send spontaneous, unwarranted, signals to the brain (Briggs, 2010; Cohen and Mao, 2014).

| Inclusions | Exclusions |

|---|---|

| Meta-reviews, systematic reviews or reviews with the primary focus of pain assessment tools in older adults with dementia | Literature failing to provide unique analysis of original or pre-existing data |

| Literature no more than 10 years old | Literature which primarily focuses on pain management, with pain assessment as an adjunct subject |

| Literature published in English |

Unrelieved pain has a number of well-documented physical and psychological long-term consequences (Baratta et al, 2014; Jeitziner et al, 2015). Physically, pain can result in significant immunosuppression, increased myocardial oxygen demand, an increased risk of thromboembolism and poor pulmonary function (Tennant, 2013; Baratta et al, 2014).

Unresolved acute pain also has the potential to result in chronic pain syndromes post discharge from care, along with psychological disorders including anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (Baratta et al, 2014; Schwartz et al, 2014; Jeitziner et al, 2015). These effects of untreated pain are no less pertinent in the cognitively impaired adult. This demographic have the same, if not greater, risk of suffering from the consequences of untreated pain as well as developing psychological disorders as a result of poorly managed pain (Tait et al, 2011).

Both the World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations (UN) have independently established that access to appropriate analgesia is a fundamental human right (Lohman et al, 2010). Despite this, current research indicates the quantity and category of analgesia administered to patients reporting pain is predominantly influenced by the attending clinician's perception of the patient's level of pain, rather than the patient's reported level of discomfort (Rose et al, 2011; Tait et al, 2011; Athlin et al, 2015). With a large number of re-presentations to acute services caused by inadequate pain management (Hwang et al, 2010; Rose et al, 2011; Tait et al, 2011; Somes and Donatelli, 2013; Athlin et al, 2015), local health districts globally have sought to improve the holistic assessment of pain in the cognitively impaired adult throughout care. This has seen the development and implementation of pain assessment tools for use by health professionals to assist in determining an appropriate analgesic regimen in the cognitively impaired adult (Rose et al, 2011; Athlin et al, 2015).

Methods

A search of the literature was conducted by the author in May 2016. The databases searched were Pubmed (Medline) and Embase. A combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms were utilised to identify articles relating to the use of pain assessment tools in the adult with dementia. The primary types of literature retrieved were meta-reviews, systematic reviews or reviews. All sub-categories of dementia were included in this review. When MeSH terms or keywords ‘paramedic’, ‘pre-hospital’, ‘EMS’ or ‘Emergency Medical Service’ were used, only one result was returned. With this considered, results from all fields of medicine were considered for inclusion in this review.

A number of the results retrieved focused primarily on the management of pain in the demented adult. While this is an important component of the holistic treatment of the cognitively impaired patient, these articles often simply reported the results of previous research into pain assessment tools without investigating the implications for current or future research and practice. Considering this, an inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed to refine the search and avoid reviews with weak analysis.

Results

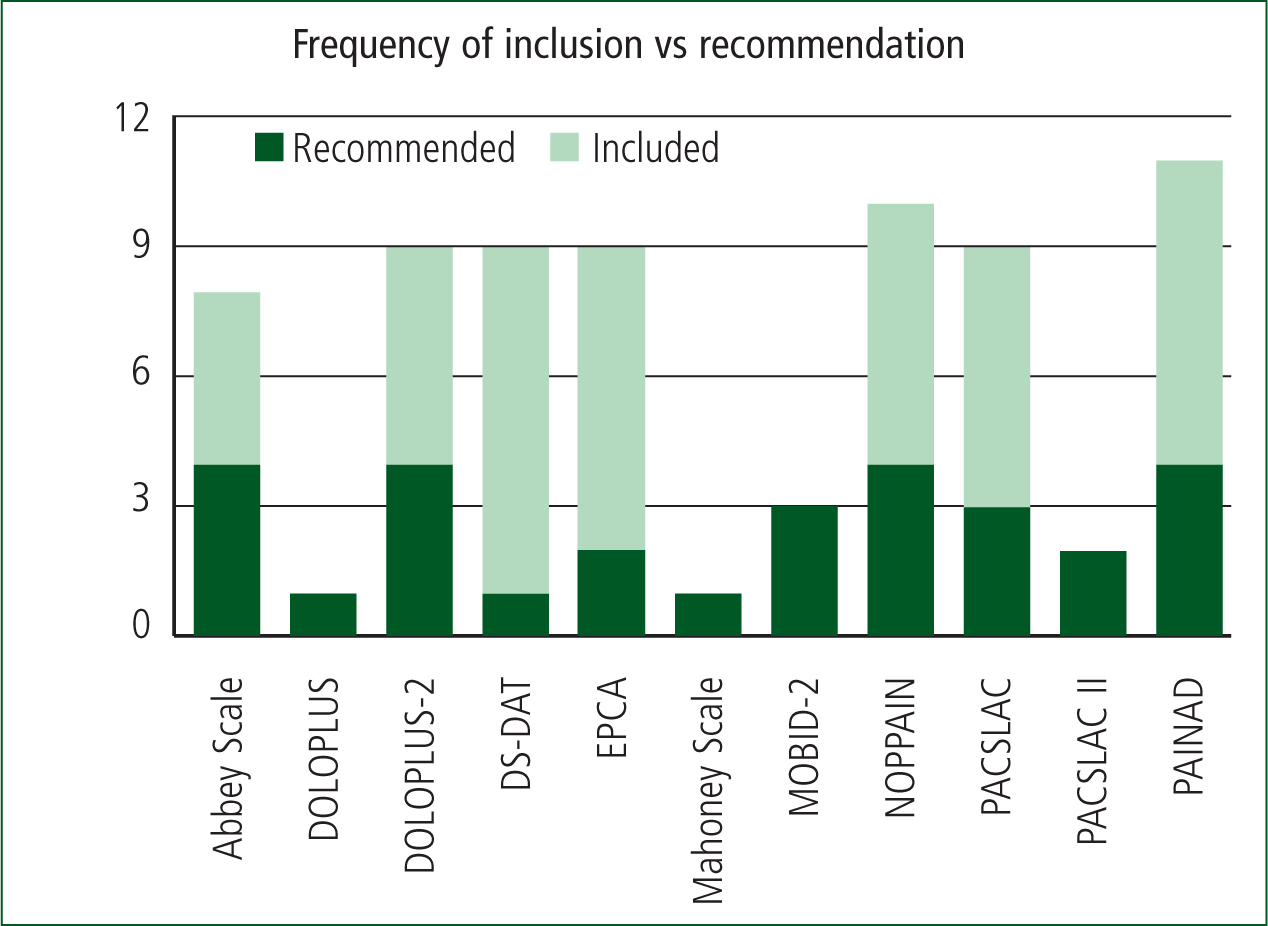

From the 12 relevant articles, 35 pain assessment tools for use in patients with dementia were identified. The following tables summarise the frequency of tool inclusion across the reviews, a short summary of the individual analysis and recommendation of each article, and a visual representation of the most frequently recommended tools.

| Review Reference | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tool name (date of publication) | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l |

| Abbey Pain Scale (2004) | x | √ | √ | x | √ | √ | x | x | ||||

| Assessment of Discomfort in Dementia [ADD] (1999) | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Behaviour Checklist (1996) | x | x | ||||||||||

| Checklist of Non-Verbal Pain Indicators [CNPI] (2000) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Comfort Checklist (2002) | x | |||||||||||

| Certified Nursing Assistant Pain Assessment Tool [CPAT] (2007) | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Discomfort Behaviour Scale [DBS] (2006) | x | |||||||||||

| DOLOPLUS (1992) | √ | |||||||||||

| DOLOPLUS-2 (2001) | x | x | √ | √ | x | x | √ | x | √ | |||

| Discomfort Scale - Dementia Alzheimer Type [DS-DAT] (1992) | x | x | √ | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Simplified Behavioural Scale [ECS] (1995) | x | x | ||||||||||

| Elderly Pain Caring Assessment [EPCA] (1998) | x | √ | √ | |||||||||

| Elderly Pain Caring Assessment 2 [EPCA-2] (2007) | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Facial Action Coding System [FACS] (1978) | x | x | ||||||||||

| Face, Legs, Activity, Cry and Consolability Pain Assessment Tool [FLACC] (1997) | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Mahoney Pain Scale (2008) | √ | |||||||||||

| Mobilisation-Observation-Behaviour-Intensity-Dementia Pain Scale [MOBID] (2007) | x | x | ||||||||||

| Mobilisation-Observation-Behaviour-Intensity-Dementia Pain Scale 2 [MOBID-2] (2009) | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||

| Nursing Assistant-Administered Instrument to Assess Pain in Demented Individuals [NOPPAIN] (2001) | x | x | √ | x | x | √ | √ | √ | x | x | ||

| Observational Behaviour Tool (1995) | x | x | ||||||||||

| Observational Pain Scale (1995) | x | |||||||||||

| Pain Assessment Checklist for Seniors with Limited Ability to Communicate [PACSLAC] (2004) | x | x | √ | x | x | x | √ | x | √ | |||

| Pain Assessment Checklist for Seniors with Limited Ability to Communicate II [PACSLAC II] (2013) | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| Pain Assessment in the Communicatively Impaired Elderly [PACI] (2003) | x | |||||||||||

| Pain Assessment for the Dementing Elderly [PADE] (2003) | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Pain Assessment Scale for Use in Cognitively Impaired Adults (2004) | x | |||||||||||

| Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia Scale [PAINAD] (2003) | x | x | √ | √ | x | x | x | x | √ | x | √ | |

| Pain Assessment in Non-communicative Elderly Persons [PAINE] (2006) | x | x | ||||||||||

| Pain Assessment Tool in Confused Older Adults [PATCOA] (2003) | x | x | ||||||||||

| Pain Behaviour Measurement [PBM] (1982) | x | x | ||||||||||

| Pain Behaviours for Osteoarthritis Instrument for Cognitively Impaired Elders [PBOICIE] (2008) | x | |||||||||||

| Proxy Pain Questionnaire [PPQ] (2002) | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Rating Pain in Dementia [RaPID] (2003) | x | x | x | |||||||||

| Rotterdam Elderly Pain Observational Scale [REPOS] (2009) | x | x | ||||||||||

a) Corbett et al, 2014 b) Flo et al, 2014 c) Hadjistavropoulos et al, 2014 d) Lichtner et al, 2014 e) Corbett et al, 2012 f) Catananti and Gambassi, 2010 g) Lord, 2009 h) While and Jocelyn, 2009 i) Bjoro and Herr, 2008 j) Schofield, 2008 k) Herr et al, 2006 l) Zwakhalen et al, 2006a

Included x Recommended √

| Authors and year | Title | Type of article | Tools assessed | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corbett et al, 2014 | The importance of pain management in older people with dementia | Review | Abbey Pain Scale, ADD, Behaviour Checklist, CNPI, CPAT, DBS, Doloplus-2, DS-DAT, EPCA, FACS, FLACC, MOBID, MOBID-2, NOPPAIN, Observational Behaviour Tool, PACSLAC, PACI, PAINAD, PAINE, PATCOA, PBM, PBOICIE, PPQ, RaPID and REPOS | MOBID-2 |

| Flo et al, 2014 | Effective pain management in patients with dementia: benefits beyond pain? | Review | ADD, CNPI, DS-DAT, Doloplus-2, EPCA-2, MOBID-2, NOPPAIN, PAINAD and PACSLAC | MOBID-2 |

| Hadjistavropoulos et al, 2014 | Pain assessment in elderly adults with dementia | Review | Abbey Pain Scale, Doloplus-2, NOPPAIN, PAINAD, PACSLAC and PACSLAC II | PACSLAC II |

| Lichtner et al, 2014 | Pain assessment for people with dementia: a systematic review of systematic reviews of pain assessment tools | Meta-review | Abbey Pain Scale, ADD, Behaviour Checklist, CNPI, Comfort Checklist, CPAT, Doloplus-2, DS-DAT, ECPA, ECS, EPCA-2, FACS, FLACC, Mahoney Pain Scale, MOBID, NOPPAIN, Observational Pain Scale, PACSLAC, PADE, Pain Assessment Scale for use in Cognitively Impaired Adults, PAINAD, PAINE, PATCOA, PBM, PPI, PPQ, RaPID and REPOS | Abbey Pain Scale, DS-DAT, Doloplus-2, ECPA, Mahoney Scale, PACSLAC and PAINAD |

| Corbett et al, 2012 | Assessment and treatment of pain in people with dementia | Review | Abbey Pain Scale, ADD, DS-DAT, CNPI, PAINAD, Doloplus-2, PACSLAC, EPCA-2, NOPPAIN and MOBID-2 | MOBID-2 |

| Catanati and Gambassi, 2010 | Pain assessment in the elderly | Review | Doloplus-2, ECPA-2, PAINAD and PACSLAC | None |

| Lord B, 2009 | Paramedic assessment of pain in the cognitively impaired adult | Review | Abbey Pain Scale, Doloplus-2, NOPPAIN and PACSLAC | NOPPAIN, Abbey or PACSLAC II |

| While and Jocelyn, 2009 | Observational pain assessment scales for people with dementia: a review | Review | Abbey Pain Scale, ADD, DS-DAT, Doloplus-2, ECPA, NOPPAIN, PACSLAC, PAINAD, PPQ | NOPPAIN and Abbey Pain Scale |

| Bjoro and Herr, 2008 | Assessment of pain in the nonverbal or cognitively impaired older adult | Review | CNPI, Doloplus-2, PACSLAC and PAINAD | PACSLAC and Doloplus-2 |

| Schofield, 2008 | Assessment and management of pain in older adults with dementia: a review of current practice and future directions | Review | CPAT, PAINAD, Doloplus, DS-DAT and NOPPAIN | Doloplus |

| Herr et al, 2006 | Tools for assessment of pain in nonverbal older adults with dementia: a state-of-the-science review | Systematic review | Abbey Pain Scale, ADD, CNPI, DS-DAT, Doloplus-2, FLACC, NOPPAIN, PACSLAC, PADE and PAINAD | None |

| Zwakhalen et al, 2006 | Pain in elderly people with severe dementia: a systematic review of behavioural pain assessment tools | Systematic review | Abbey Pain Scale, CNPI, Doloplus-2, DS-DAT, ECPA, ECS, NOPPAIN, Observational Pain Behaviour Tool, PACSLAC, PAINAD, PADE, RaPID and Pain Assessment Scale for use with Cognitively Impaired Adults | Doloplus-2, ECPA, PACSLAC and PAINAD |

Discussion

A number of pain assessment tools identified in this review show promising early results in the detection of pain in adults with dementia. However, the literature also highlights a number of areas for development before any one tool could be recommended for use in a clinical setting (Zwakhalen et al, 2006a; Herr et al, 2006; Bjoro and Herr, 2008; While and Jocelyn, 2009; Hadjistavropoulos et al, 2014; Corbett et al, 2014). The literature consistently argues that providing a pain assessment tool will likely improve the detection of pain in adults with dementia (Herr et al, 2006; Schofield, 2008; Bjoro and Herr, 2008; While and Jocelyn, 2009; Lord, 2009; Corbett et al, 2012; Lichtner et al, 2014). However, the same literature states that to achieve best outcomes for patients, it is essential that the implementation of any tool is accompanied by appropriate education into the behaviours exhibited by cognitively impaired adults in pain (Herr et al, 2006; Bjoro and Herr, 2008; Schofield, 2008; While and Jocelyn, 2009; Lord, 2009; Corbett et al, 2012; Lichtner et al, 2014).

In 2002, the American Geriatric Society (AGS) proposed six main behaviours exhibited by adults with cognitive impairment when in pain (AGS Panel on Persistent Pain in Older Persons, 2002). Since this landmark proposal, pain assessment tools have aimed to accurately assess each of these pain behaviours, and it is in these behaviours the literature recommends clinicians are educated (Herr et al, 2006; Schofield, 2008; Bjoro and Herr, 2008; While and Jocelyn, 2009; Corbett et al, 2012; Corbett et al, 2014). The behaviours identified by the AGS are alterations in facial expressions, verbalisations and body language, as well as changes in interpersonal interactions, activity patterns and mental status (AGS Panel on Persistent Pain in Older Persons, 2002). By providing education into these behaviours, prior to the implementation of a pain assessment tool into clinical practice, clinicians will be better poised to successfully identify situations in which the tool may be useful in assessing the intensity of a patient's pain.

Furthermore, the literature highlights a lack of data surrounding inter-rater reliability, intra-rater reliability and test-retest scores. In a number of the tools identified in this review, this data was reported without evidence or totally absent (Zwakhalen et al, 2006a; Herr et al, 2006; Bjoro and Herr, 2008; While and Jocelyn, 2009; Hadjistavropoulos et al, 2014; Corbett et al, 2014). Where present, the reliability of this data was often hindered by small sample sizes and poor outcome measures, specifically, the use of nurse perception of pain as the comparative measure (Zwakhalen et al, 2006a; Herr et al, 2006; Bjoro and Herr, 2008; While and Jocelyn, 2009; Hadjistavropoulos et al, 2014; Corbett et al, 2014). Despite this lack of supportive data there are a number of tools reported in the literature as having a strong conceptual foundation, which, with further development and testing, would make excellent additions to clinical practice. A short summary of the most consistently recommended tools and their potential applications to out-of-hospital practice follows.

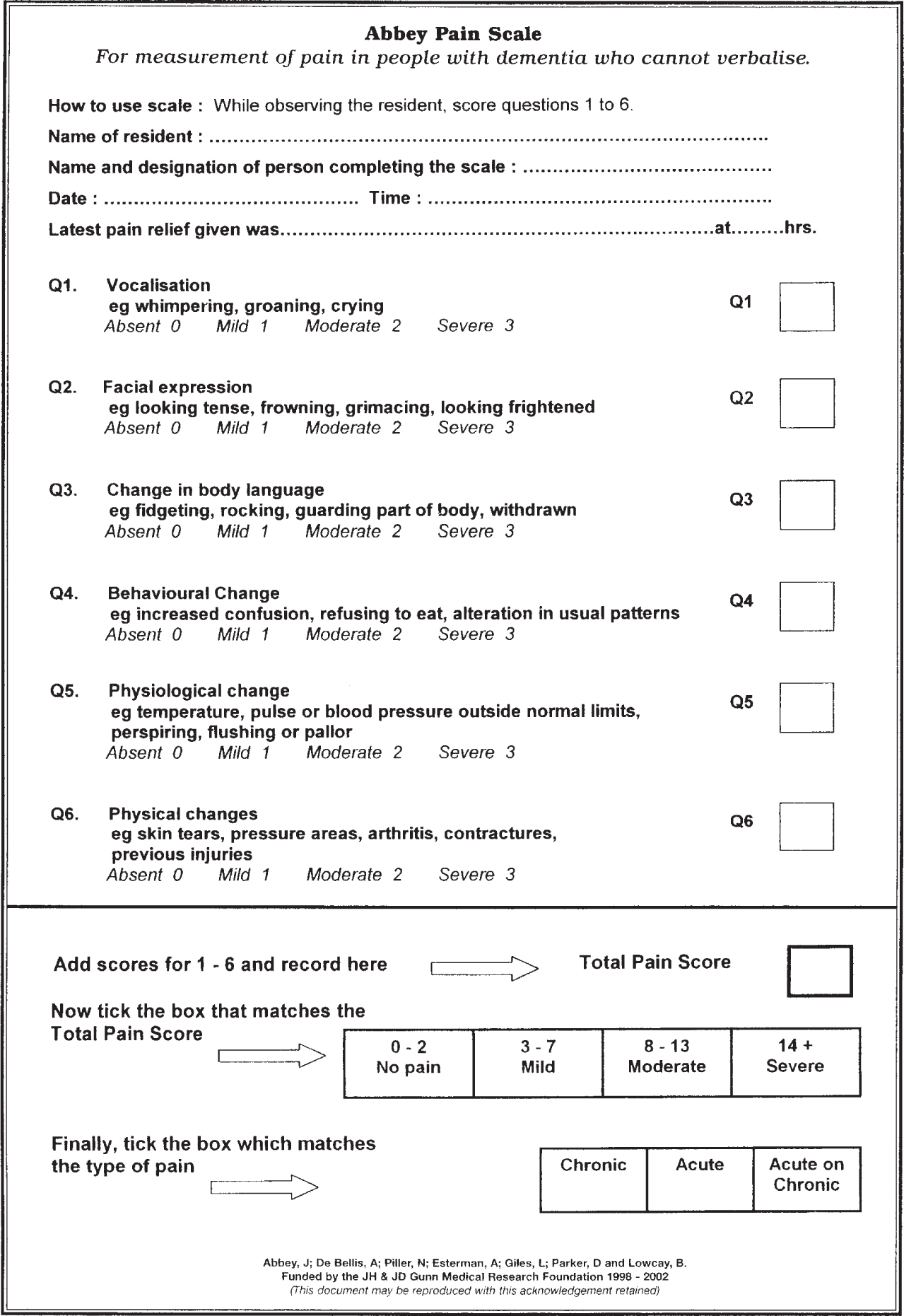

The Abbey Pain Scale

The Abbey Pain Scale was initially developed by Abbey et al in 2004 as a means of assessing pain in patients with end stage dementia and is one of the strongest candidates for implementation into out-of-hospital practice (Abbey et al, 2004). The Abbey Pain Scale is a six item scale with each item rated one to three, and the scores then collated (Abbey et al, 2004). The total score is matched against a scale with values assigned to no pain, mild pain, moderate pain and severe pain respectively. Preliminary testing of the tool was conducted in a residential home utilising the sub-par comparison against nurse's perceptions of pain in cognitively impaired adults (Abbey et al, 2004). Further testing with improved outcome measures, but limited sample sizes, have reported satisfactory levels of internal consistencies and good differentiation between states of pain and no pain (Zwakhalen et al, 2006a; Hadjistavropoulos et al, 2014; Lichtner et al, 2014). The Abbey Pain Scale represents a strong candidate for use in out-of-hospital practice as it requires no prior knowledge of the patient or their baseline cognitive state, eliminating the need for a carer or relative well known to the patient to report the presence of pain. It utilises simplistic individual scoring items, requires minimal, if any, prior training and is reported as a time-effective assessment tool (Abbey et al, 2004; Zwakhalen et al, 2006a; Hadjistavropoulos et al, 2014; Lichtner et al, 2014).

Doloplus-2

The Doloplus-2 is a refined version of the 15-item Doloplus Scale, originally developed by Bernard Wary in 1992 (Holen et al, 2007). Streamlined by geriatricians to better reflect pain behaviours specific to older adults, the Doloplus-2 is a 10-item tool designed for the assessment of pain in older adults with communication disorders (Holen et al, 2007; Pautex et al, 2007). Split into three subcategories: somatic, psychosocial and psychomotor, each item is scored from one to three to reflect increasing levels of the particular behaviour, with a total score of five or over indicating the presence of pain (Holen et al, 2007; Pautex et al, 2007; Torvik et al, 2010). Trials have indicated Doloplus-2 correlates well with self-assessment of pain in cognitively intact adults and has satisfactory levels of internal consistencies (Holen et al, 2007; Pautex et al, 2007). Unfortunately, despite its strengths the Doloplus-2 appears to have limited applications in out-of-hospital practice. A number of the items on the scale require significant prior knowledge of the patient's baseline cognitive state and their ability to complete daily activities of living, while the extensive nature of the scale itself requires substantial time to complete thoroughly. A revision, such as that proposed by Pautex et al (2007), may have more relevance to the out-of-hospital environment in future.

MOBID-2

The MOBID-2 is an extended version of the MOBID scale, which was originally designed as an observational pain tool for patients with advanced dementia (Husebo et al, 2014). In the first part of MOBID-2, musculoskeletal pain is assessed as clinicians observe pain behaviours (vocalisations, facial expressions and defence movements) throughout five guided movements (Husebo et al, 2014). The clinician subsequently notes the presence of any pain behaviours during these movements and assigns a score of zero to 10 based on the intensity of the behaviour (Husebo et al, 2010; Husebo et al, 2014). The second part of the MOBID-2 assesses pain originating from internal organs, the head and the skin by observing the same pain behaviours as they are expressed by the patient at rest or during clinical examination (Husebo et al, 2010). These pain behaviours may be observed over minutes, hours or days, depending on the clinical setting and are scored identically to the guided movements of Part One (Husebo et al, 2010; Husebo et al, 2014). Once complete, the clinician is asked to provide a score between zero to 10 based on their overall impression of the intensity of pain experienced by the patient (Husebo et al, 2010). MOBID-2 has been found to have satisfactory levels of internal consistencies, although these were slightly lower than the original MOBID scale, with moderate levels of test-retest consistencies reported (Husebo et al, 2010). The concurrent validity of the MOBID-2 scale is also reported as satisfactory as there was an association between the intensity assessed by nurses and physicians (Husebo et al, 2010). This, however, is not an ideal measurement for assessing the validity of a tool and is widely acknowledged in the literature as requiring further validation (Husebo et al, 2010; Husebo et al, 2014). In regards to applications to out-of-hospital practice, the MOBID-2 represents a tool that warrants further exploration. The tool is comprehensive, assessing various sources of pain through simple to follow instructions in a systematic manner. However, the tool remains heavily reliant on individual interpretations of pain behaviours, hardly representing an independent assessment of the presence of pain in the demented adult. In initial validations of the tool, it was also noted by nursing staff that for best results it was desirable, but not essential, to have prior knowledge of the patient and their baseline cognitive status (Husebo et al, 2010).

| PAIN ASESSMEMENT IN ADVANCED DEMENTIA (PAINAD) SCALE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | Score = 0 | Score = 1 | Score = 2 | Score |

| Breathing (independent of vocalisation) | Normal |

|

|

|

| Negative vocalisation | None |

|

|

|

| Facial expression | Smiling or inexpressive |

|

|

|

| Body language | Relaxed |

|

|

|

| Consolability | No need to console |

|

|

|

| Total | ||||

PACSLAC-II

Although the original PACSLAC was rated as one of the most clinically useful observational pain tools developed in the last 15 years, the size of the tool and the subsequent length of time required to complete it necessitated revision (Zwakhalen et al, 2006b; Chan et al, 2014). The PACSLAC-II is a 31-item checklist, divided into six sections focusing on key pain behaviours observed in adults with cognitive impairment (Chan et al, 2014). No interpretation guide exists for use with the PACSLAC-II, the authors noting that increasing scores simply increase the likelihood the patient is currently experiencing pain (Chan et al, 2014). The authors are also careful to note that the tool is not an absolute indication of the presence or absence of pain and that a low score does not necessarily exclude pain in the cognitively impaired adult (Chan et al, 2014). The PACSLAC-II has demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency and inter-rater reliability and was able to differentiate between states of pain and no pain (Chan et al, 2014).

Originally developed for use in long-term care facilities, the applications of PACSLAC-II to out-of-hospital practice are likely limited. The PACSLAC-II was designed to provide an indication of long-term fluctuations in the experience of pain by residents of long-term care facilities, with comparisons against previous days or months scores. While it may be useful in distinguishing the presence of pain, the limited length of patient contact by out-of-hospital providers will likely impede the likelihood of a change in score post short-term analgesia.

PAINAD

Developed in a residential setting, the PAINAD is a five-item scale developed for the detection of pain in non-verbal adults with advanced dementia (Horgas and Miller, 2008). Originally produced based on the DS-DAT scale and FLACC scale, the authors of PAINAD attempted to closely align their scale with the pain behaviours identified by the American Geriatric Society as more prevalent in adults with dementia (Horgas and Miller, 2008). Each item is scaled from zero to two based on criteria established within the scale to form a total score out of 10 (Horgas and Miller, 2008; Liu et al, 2010). Initially the authors recommended the PAINAD be used as a measure of increasing or decreasing levels of pain over a given time period, however, the PAINAD has been shown to be appropriate for use as an assessment of acute pain (Liu et al, 2010; Zwakhalen et al, 2012). Although the original authors did not provide a scale for interpretation, it is generally accepted that scores of one or two indicate the need for non-pharmacological interventions, while a score of three or higher indicates the need for the implementation of a pharmacological regime (Liu et al, 2010; Zwakhalen et al, 2012). The PAINAD has been shown to have consistently high levels of reliability and validity, with good internal consistencies (Horgas and Miller, 2008; Liu et al, 2010; Zwakhalen et al, 2012). It must be noted, however, that the PAINAD has been demonstrated to be confounded by the presence of psychosocial distresses, and as such the use of the tool must be in conjunction with a holistic assessment of the patient's circumstance (Jordan et al, 2011). The PAINAD requires minimal training, is able to be completed in less than 5 minutes and is aligned with the standard zero to 10 rating of pain intensity (Horgas and Miller, 2008; Liu et al, 2010; Zwakhalen et al, 2012). Further, the use of PAINAD requires no prior knowledge of the patient or their baseline cognitive state (Horgas and Miller, 2008; Liu et al, 2010; Zwakhalen et al, 2012). With these factors considered, the PAINAD represents a viable option in the out-of-hospital environment and further investigation into its applications in this environment is warranted.

Conclusion

Out-of-hospital clinicians are often the first to assess patients in the community and provide subsequent care. With the growing scope of practice afforded to these clinicians it is essential they are provided with the appropriate education and equipment to make informed diagnoses and treat accordingly. Older adults with cognitive impairment, caused by conditions such as dementia, are recognised as an at-risk group for poor pain assessment, management and subsequent representation to acute medical services. In this review, the Abbey Pain Scale and PAINAD have been identified as tools substantiated in the literature for use in detecting pain in adults with dementia, which likely have applications in the out-of-hospital environment. Current research has indicated their use has improved the assessment of pain in cognitively impaired adults when implemented in conjunction with appropriate education into the pain behaviours identified by the AGS. With this considered, a trial of either the Abbey Pain Scale or PAINAD in an emergency ambulance service is appropriate and likely warranted to assess their impact on pain assessment in this vulnerable patient group.