Sepsis is a life-threatening condition, a common cause of shock and is a major killer in the UK, with mortality rates quoted at 37 000 deaths annually (Daniels, 2012). The UK Sepsis Group (2011) estimated that patients with sepsis are six times more likely to die than patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) or acute stroke—two conditions with high mortality that are managed using ratified pre-hospital protocols. Sepsis embodies a range of clinical conditions; it is a systemic inflammatory response to infection in which clinical deterioration can progress rapidly. It is defined by Dellinger et al (2013) as the presence of infection that stimulates a systemic response; severe sepsis is sepsis-induced tissue hypoperfusion, and the most critical end of this spectrum is septic shock, resulting in profound hypotension despite adequate fluid resuscitation. This inflammatory response results in multiple immunological and circulatory effects, which can rapidly progress to multi-organ failure and death, (Baudouin, 2008; 1–4), therefore presenting a considerable and complex challenge to all clinicians.

Early identification of this time-critical syndrome is widely acknowledged to be clinically challenging (Seymour et al, 2009). Significant evidence exists to support the strong association between timely intervention and the attainment of optimal patient outcomes; most notably, the landmark study by Rivers et al (2001), which determined that early goal-directed therapy (EGDT) can improve survival by up to 16%. The impact of immediate treatment for severe sepsis was demonstrated in a study by Kumar et al (2006), which concluded that for each hour's delay in antibiotic administration, mortality increases by 7.6%.

While carrying out this literature review, it became apparent that comparisons are frequently drawn between pre-hospital care of severe sepsis and other time-critical conditions. In particular, it is often reported that paramedics have made significant contributions in improving outcomes for patients with AMI and stroke by providing early recognition, enabling early aggressive intervention and transportation to the appropriate specialist facility. Clearly an equivalent level of care needs to be adopted for patients with sepsis. A particular difficulty for pre-hospital clinicians is that the early signs of sepsis can be non-specific; recognising sepsis is more challenging than identifying either AMI or stroke patients, who generally present with definitive signs and symptoms. Daniels (2012) advises that the UK Sepsis Group is working with ambulance trusts and general practitioners to trial systems for the timely identification of pre-hospital sepsis and to facilitate communications with receiving hospitals. It is well-recognised that the pre-alerting system enables hospital clinicians to mobilise specialist teams in order to continue early aggressive treatment.

A recently published report by the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman (2013) highlighted significant failings in the overall management of sepsis; this document focused on 10 patients who died as a result of shortcomings in their treatment. The Ombudsman worked with NHS England, the College of Emergency Medicine (CEM), the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the UK Sepsis Trust to identify solutions; the principal recommendations made were improved recognition and management of sepsis, the provision of clear clinical guidance and the urgent need for further research.

A prospective, observational study by Esteban et al (2007) indicated that 71% of sepsis cases had community-acquired infection. The advancement of pre-hospital sepsis care is fundamental to improving outcome, as this environment is often the first point of contact for this patient group. Opportunities evidently exist for pre-hospital clinicians to advance existing standards in the overall management of sepsis.

Search strategy

A comprehensive literature review was completed to evaluate the available evidence, undertaken in late 2013. The question under review (Can pre-hospital recognition and intervention improve outcome in severe sepsis?) was developed from the author's differing experiences of managing patients with severe sepsis, in both pre-hospital and emergency inpatient settings; the question is focused on the potential for improved patient outcome as a result of earlier recognition of sepsis, and consequently, more timely EGDT.

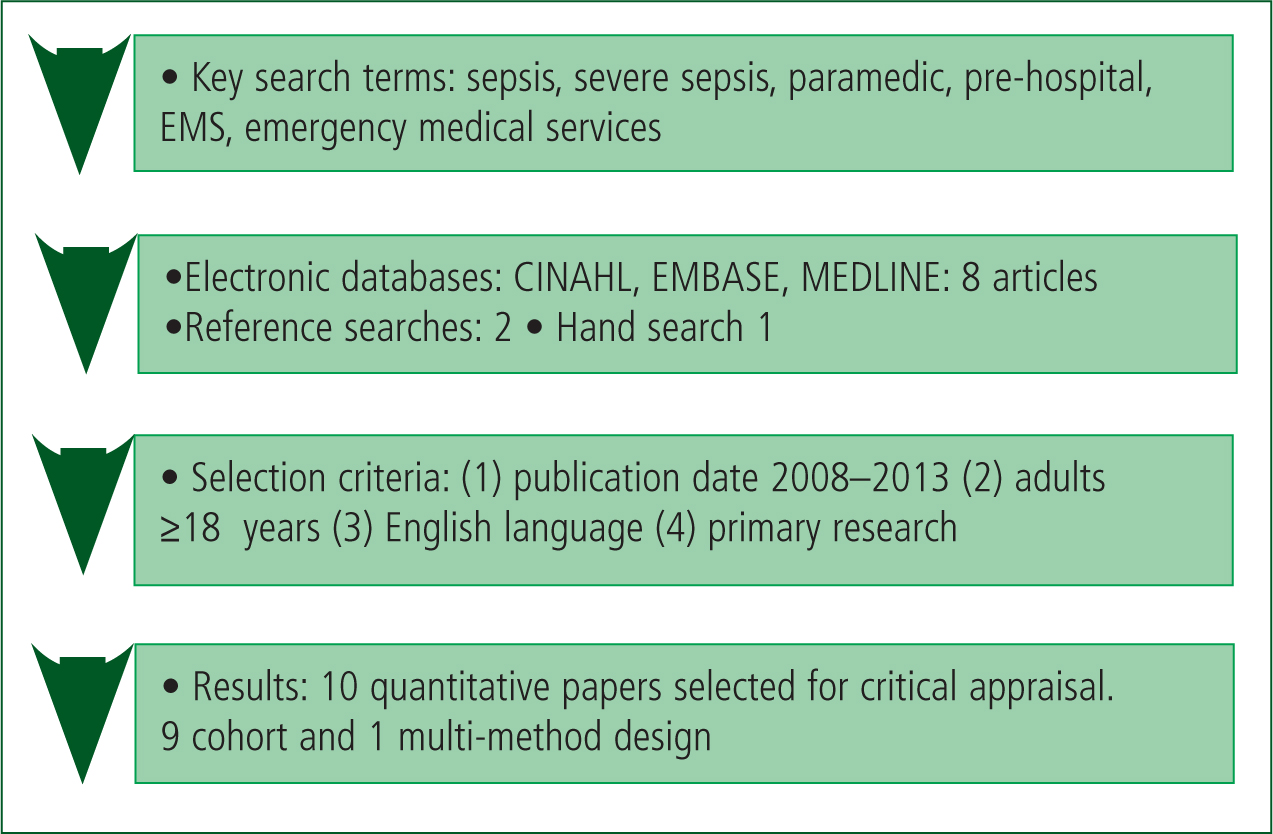

An introductory search of these databases produced a high volume of articles, indicating the need for refinement strategies. Sepsis is a broad subject; the searches were therefore further narrowed using inclusion and exclusion criteria to produce a reasonable number of focused papers. It became apparent that comparatively little has been published on the focused subject of pre-hospital sepsis management.

Date limits were selected to include literature published after 2008, based on a relative lack of earlier research. Pre-hospital sepsis screening tools (SST) are currently being introduced in the UK. These are principally designed for patients over the age of 16 years, as the physiological parameters are based on adults (McClelland and Younger, 2012), hence the selection of the age limit for inclusion criteria.

Following exclusion of duplicates there were 24 articles remaining, subsequent review of the titles and abstracts produced eight relevant papers for critical appraisal. Additional papers were identified: two through conducting secondary searches of references and one from a hand search of the Journal of Paramedic Practice.

In addition, valuable supplementary information was obtained following discussion with practising medical consultants and paramedics with an interest in sepsis. Following preliminary review of the material one paper was rejected; the final ten articles selected are all observational studies which places them in the mid-range of the hierarchy of evidence; nine are cohort studies and one is a multi-method design. In the following review, references to the ten critiqued articles can be found in Appendix 1.

Review

This review delivers a comprehensive critical analysis of the literature appraisal findings on completion of which three distinct themes emerged:

Pre-hospital incidence of severe sepsis, patient characteristics and outcomes

Many septic patients are seen initially by pre-hospital clinicians, yet there appears to be a lack of research on the characteristics of these patients, on the level of care provided and subsequent impact on outcomes; this is emphasised in three of the research papers (Seymour et al, 2010; Wang et al, 2010; Band et al, 2011).

A significant number of patients with severe sepsis are transported to hospital by ambulance. An important Scottish audit focusing on emergency care of patients with sepsis (Scottish Audit Trauma Group, 2010) revealed that these cases numbered 73%. This contrasts with findings from the papers reviewed, mostly of American origin; the overall incidence rate of cases hospitalised with severe sepsis, who were cared for by EMS clinicians was estimated to be between 34% and 51% (Studnek et al, 2010; Wang et al, 2010; Band et al, 2011; Seymour et al, 2012). Nonetheless, these numbers are increasing; a substantial retrospective cohort study by Seymour et al (2012), conducted over a decade, reported an 11.8% increase per annum. These findings would suggest that pre-hospital care offers important opportunities for management of this time-critical syndrome, particularly as these patients are potentially of higher acuity.

A robust, prospective cohort study conducted by Wang et al (2010), concluded that EMS personnel cared for the majority of patients requiring early EGDT, including haemodynamically unstable patients with septic shock. This corresponds with research by Studnek et al (2010), who noted a higher percentage of patients with organ failure; and Seymour et al (2012), who found that 19% of cases with severe sepsis were considered to be life-threatening, yet the majority of these were not diagnosed until hospital admission. Variability in pre-hospital care was found to be common in this study and also in an earlier study by Seymour et al (2010), when only 40% of patients found to have septic shock on arrival at hospital had received vital intravenous (IV) fluid resuscitation.

Three studies identified respiratory tract infection as the most common source of sepsis (Seymour et al, 2010; Studnek et al, 2010; Wang et al, 2010). The UK Sepsis Group (2011) concurs, and has reported that the majority of sepsis cases are caused by community-acquired bacterial infection, sensitive to antibiotic therapy. Robson et al (2009) advocate the use of pre-hospital antibiotics for patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) as a starting point.

Patients with sepsis receiving EMS care were more likely to have septic shock, be elderly and have a high number of co-morbidities; Seymour et al (2012) propose that an ageing population could, in part, account for the increasing incidence of sepsis. A recent clinical audit by the Royal College of Emergency Medicine (2012) recognises that elderly patients with sepsis can be more challenging to diagnose; the presence of multiple co-morbidities may complicate diagnosis and presenting symptoms can be vague. It is apparent that identifying sepsis can be difficult for all cases, not just for older patients; the early signs and symptoms are often non-specific. Seymour et al (2012) determined that although EMS clinicians spent a considerable length of time on scene, recognition was poor and interventions minimal; a contributing factor was that many patients hospitalised with severe sepsis had been classified as non-urgent, and consequently would not have received paramedic care.

Evidence also suggests that EMS transport to hospital is in itself associated with shorter time to treatment. The studies by Studnek et al (2010) and Band et al (2011) both determined that pre-hospital care was associated with improved in-hospital processes by significantly reducing the time to the initiation of EGDT. A further reduction in time to definitive treatment was realised if sepsis was recognised by EMS personnel (Studnek et al, 2010), again supporting the proposal for screening tools. A clear benefit of such recognition is that the receiving medical unit can be pre-alerted.

Mortality rates quoted for EMS transported patients across the studies are variable. Guerra et al (2013) used a retrospective study to assess mortality rates for EMS patients with severe sepsis; this was calculated at 26.7%, which the researchers state is in line with findings of recent studies. This research by Guerra et al (2013) was found to lack precision, with many limitations acknowledged by the authors. However, data were comparable to mortality rates stated by Seymour et al (2012), Studnek et al (2010) and Seymour et al (2010). In order to assess whether mortality could be decreased by an accurate diagnosis, Guerra et al (2013) created a sepsis alert protocol, which when initiated saw mortality decrease from 26.7% to 13.6%.

Overall, these papers reveal comparable findings in the analysis of characteristics of this high-acuity patient group. Patients who received initial EMS care were more likely to:

Recognition and diagnostic aids

Recognising severe sepsis quickly and accurately in the pre-hospital environment is challenging; physical findings are typically non-specific and the definitive diagnostic tests, such as microbiology, are not accessible in this setting. Seymour et al (2012) reported that up to 80% of severe sepsis cases were not diagnosed until admission to the Emergency Department (ED).

Of particular relevance are point-of-care lactate measurements and validated sepsis screening tools (SST); these SSTs may incorporate the National Early Warning Scoring system. Two papers specifically evaluate the prognostic value of serum lactate testing (Jansen et al, 2008 and van Beest et al, 2009) for severe sepsis. Lactate has clearly been identified as a leading biomarker for tissue hypoperfusion and end-organ failure in the hospital setting; the accepted threshold for initiation of EGDT is 4 mmol/l (Rivers et al, 2001). There is a necessity for more sensitive parameters to be used by paramedics; van Beest et al (2009) found that mortality was significantly increased in normotensive shock patients if pre-hospital lactate levels were ≥4 mmol/l. Pre-hospital lactate testing presents an opportunity for the earlier detection of this cryptic shock (Jansen et al, 2008), and could provide the trigger for fluid resuscitation in patients who may not otherwise have been identified.

Pre-hospital serum lactate testing has been facilitated by the introduction of point-of-care meters. Although study findings from Seymour et al (2012) suggest that lactate levels carry prognostic value and provide superior information than that obtained from standard vital signs, expert opinion from Daniels (2011) states that there is debate regarding the validity and interpretation of singular lactate measurements, advising that serial levels are more effective in guiding response to resuscitation and fluid therapy. However, van Beest et al (2009) emphasise the value of an early lactate reading to inform triage decisions and enable advanced activation of staff in the receiving ED.

Another area of discussion concerns the reliability of lactate levels obtained from venous blood, as compared to arterial blood levels. Pearse (2009) considers that lactate concentrations are often higher in peripheral blood samples but not by a predictable margin. In contrast, van Beest et al (2009) believe there is a good correlation between these methods and recommend that venous lactate testing is clinically relevant. This view is supported by Surviving Sepsis Guidelines, which state that there is no consensus in the literature on this question; they advise that arterial or venous samples can be used (Dellinger et al, 2012).

Guerra et al (2013) hypothesised that EMS clinicians could improve outcomes by identifying and treating severe sepsis before arrival at the ED using a sepsis alert tool, including serum lactate testing; in this study paramedics were able to identify patients with severe sepsis with 48% accuracy. Reduced mortality was observed for patients identified and treated using this alert protocol at 13.6%.

Improving early recognition of sepsis was a primary recommendation of the clinical report by the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman (2013); this group worked closely with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), and other relevant organisations, to find solutions for the shortcomings identified in sepsis care across the NHS. As a consequence, NICE are formulating guidance to support GPs and ambulance clinicians in improving outcomes.

As yet, there are no standardised guidelines for ambulance services in this country; the UK Sepsis Group (2011) identified inequalities in delivery of pre-hospital care, significantly in relation to recognition. Lactate measurements are often linked to SSTs, providing a catalyst for treatment pathways. Pre-hospital SSTs are based on clearly defined physiological variables; four of the studies advocate the implementation of screening tools (Seymour et al, 2010; Studnek et al, 2010; Wang et al, 2010; Guerra et al, 2013). In addition, Seymour et al (2012) established that the most severe cases were identified in the ED, when the time critical window for early aggressive treatment may have already passed.

In the absence of validated pre-hospital sepsis guidelines, the UK Sepsis Group (2011) recommended that ambulance Trusts introduce local protocols; every Trust should have well-defined strategies for improving sepsis outcomes. Many services have now implemented screening tools based on the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) care bundles.

The overall consensus is that much needs to be achieved to maximise outcomes and that there is scope to realise significant improvements. Additionally, these studies all proposed that further rigorous research is required.

Theraputic interventions

The concluding theme focuses on pre-hospital therapeutic interventions for patients with severe sepsis, with particular emphasis on the time-sensitive treatments of administration of IV fluids and IV antibiotics. The landmark paper by Kumar et al (2006) revealed that for each hour's delay in antibiotic administration, in septic shock, there was an associated 7.6% increased mortality.

The primary goals of the widely used Sepsis Six pathway include three therapeutic interventions: the early administration of high-flow oxygen, IV fluids and IV antibiotics. Cautious early fluid challenges are key to the management of sepsis (Dellinger et al, 2012). Research by Seymour et al (2010) concluded that only 30% of ALS transported patients with severe sepsis received IV fluid, and this increased to just 38% among patients diagnosed with septic shock; variability in pre-hospital management was evident, indicating the need for standardisation of care.

Band et al (2011) showed that arrival at the ED by EMS was associated with significantly shorter time to initiation of IV fluids: median time to initiation of IV fluids was 34 minutes for EMS and 68 minutes for non-EMS patients. It could be said that arrival at the ED by ambulance results in faster medical attention, but when severe sepsis has been diagnosed by paramedics, the receiving ED can be alerted to activate appropriate resources.

Recommendations made by the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman (2013) to raise standards of sepsis care, highlights the need to clarify protocols for optimal fluid resuscitation, which will inform pre-hospital practice. Actions have been formulated as a result of this clinical report, including the proposed setting of standards by NICE, to include guidance on timely administration of IV fluids and IV antibiotics.

Evidence-based guidelines recommend that broad spectrum antibiotics are administered within 1 hour of diagnosis for patients with severe sepsis (Dellinger et al, 2012); however, although strong evidence supports this intervention, the feasibility of achieving this has not yet been scientifically evaluated.

The UK Sepsis Group (2011) recommended that if ambulances have a prolonged transit time (over 45 minutes) then consideration should be given to making provision for the administration of antibiotics en-route to hospital. Robson et al (2009) concur with this view and advise that, in addition, blood cultures should be obtained before administering antibiotics in order to target appropriate therapy. The evidence clearly suggests that prompt delivery of IV fluids and antibiotics can improve outcomes in severe sepsis and that attention needs to be focused on optimising delivery of time-dependent interventions when journey times are prolonged.

Conclusions and implications for practice

Appraisal of the literature indicates that the optimum care of patients with severe sepsis needs to start in the pre-hospital setting. Evidence has identified that significant opportunities exist to improve existing care to optimise outcomes:

Although introducing changes to practice can be challenging, these recommendations are considered feasible. A multidisciplinary approach would be beneficial to facilitate the development of integrated clinical pathways between primary and secondary care clinicians.