Nearly half of deaths (45%) in England and Wales occur at home or in care homes (Public Health England, 2018). Ambulance services are often called to people close to death because of sudden crises, worsening symptoms or anxious caregivers, especially when community care provision is lacking (Ingleton et al, 2009). Clinicians then need to make time-critical decisions concerning resuscitation if no decision has been documented about this in advance.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is the default treatment unless a do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation (DNACPR) form is in place, under conditions unequivocally associated with death or where a paramedic assesses that death is imminent because of terminal illness (Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee (JRCALC), 2016).

National policy recommends that patients at risk of cardiac arrest are identified, and decisions made in advance as to whether attempted CPR would be appropriate and desired. The decision is recorded on dedicated DNACPR documentation and applies only to CPR; all other appropriate patient treatment and care should continue (Resuscitation Council (UK) (RCUK), 2014).

In the absence of an integrated DNACPR policy in England, many regions have introduced shared policies and standardised, patient-held DNACPR forms that are recognised across care settings. Despite this, considerable variation remains in the portability of DNACPR decisions between organisations and across the community/acute care interface (Freeman et al, 2015), with multiple forms in use in some areas (Clements et al, 2014).

DNACPR forms are part of a complex process which includes:

For some time, this process has been common practice in hospital, where around 80% of those who die have a DNACPR in place (Aune, 2005; Fritz et al, 2014). However, DNACPR forms are not routinely completed (Cohn et al, 2013; Perkins et al, 2016), so patients may remain for resuscitation inappropriately (National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death (NCEPOD), 2012) and DNACPRs are frequently misunderstood by health professionals. Furthermore, they have been associated with a lower likelihood of patients receiving some treatments, reduced levels of monitoring activity and less urgent escalation to senior support (Fritz et al, 2010; Mockford et al, 2015).

Existing evidence base

Three databases were searched—CINAHL, Medline and PubMed—because of their relevance and accessibility (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2019). The databases were searched, combining the MESH terms/key words ‘ambulance OR paramedic* AND do not resuscitate orders*’. Twenty-eight abstracts were identified and four had relevance.

Because of the limited number of articles relating to the prevalence and use of DNACPRs in the community and how they may be interpreted and used by ambulance clinicians, it is key to first determine any existing gaps in understanding.

The aims of the present study were to investigate:

Methods

A modified sequential explanatory design was used (Cresswell and Plano Clark, 2011). A qualitative interview study to identify major themes was followed by a larger quantitative online survey to establish generalisability, with data integrated during analysis and interpretation.

Participants

Interviews

Paramedics, ambulance technicians and care assistants who had worked in the East of England Ambulance Service Trust (EEAST) for a minimum of 2 years were invited to participate in interviews through an invitation letter sent to ambulance stations. From 19 expressions of interest, the research team purposively sampled potential participants by seniority and years of experience, and 10 participants agreed to be interviewed.

Individual interviews took place at participants' homes or places of work; one focus group was held. Participants were given a £30 voucher in recognition of their time. The semi-structured interview schedule used open questions, providing a consistent framework while allowing participants to speak reflectively. Interviews lasted 25–60 minutes and the focus group took 75 minutes.

Questionnaire

All 350 ambulance clinician delegates who enrolled at the inaugural Innovation for Pre-Hospital Emergency Care (IPHEC) conference in 2015 in Brighton were emailed a link to an anonymous online questionnaire before the event. Most response categories were fixed, and free-text comments were also invited.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Cambridge psychology research ethics committee and Warwick University biomedical and scientific research ethics committee for the qualitative and quantitative studies respectively. Research and development authorisation was obtained from EEAST.

Data analysis

Interviews were audiotaped, transcribed verbatim and anonymised. Field notes recorded insights and questions generated during interviews and a reflective diary was maintained. Data analysis followed the five key stages of thematic analysis: familiarisation; identification of a thematic framework; indexing; charting; and interpretation (Richie and Spencer, 1994). Analysis was undertaken by the lead author (SM), with emergent themes discussed at regular meetings with second (ZF) and fifth authors (SB).

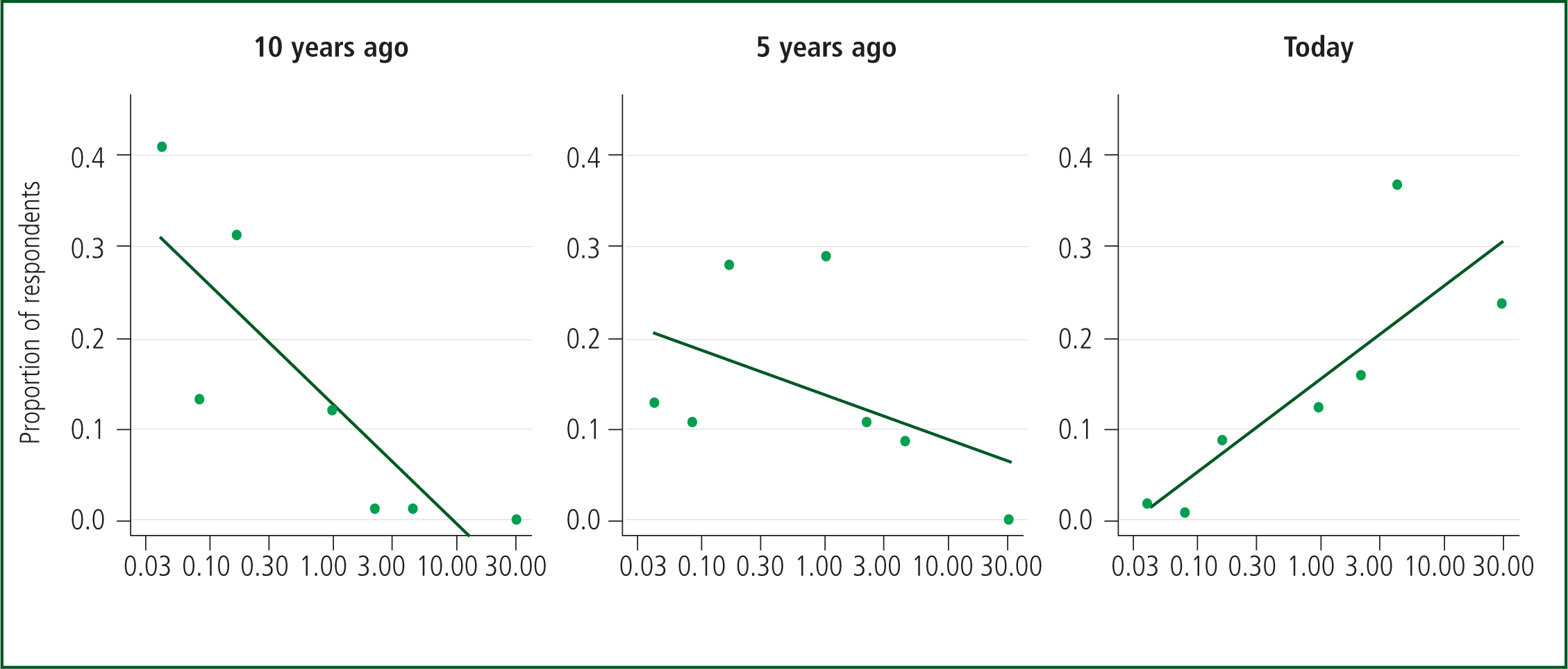

Initial descriptive statistical analysis of survey data was followed by multiple linear regression (by fourth author, MP) using R (R Core Team, 2019). The proportion of respondents was regressed against the log of the number of times DNACPRs were seen per month and at what time (today; 5 years ago; and 10 years ago) and the interaction between them. Log was used as the relationships appeared linear on this scale with approximately constant variance. Evidence of interaction reveals changes in frequency of DNACPR over time (with 95% confidence intervals).

Results

Demographics

In total, 19 potential participants who expressed an interest were sent a letter via their workplace email; 18 replied but only 10 were available to participate.

The participants consisted of seven men and three women, who had worked in emergency medical services for periods ranging from 2–24 years. Seven were paramedics; two were emergency medical technicians; and one was an emergency care assistant with experience of working with patients near the end of life. Participant demographics are shown in Table 1.

| Interviews (10 total) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 7 male | 3 female | ||

| Profession | Paramedic (7) | EMT (2) | ECA (1) | Other |

| Questionnaire (123 total) response rate 123/350 (35%) | ||||

| Profession | Paramedics: 80 (65%) | Other: 29 (24%) | Student paramedics: 14 (11%) | |

| Years of experience | 11+ years (35%) | 8–11 years (19%) | 0–3 years (10% | Students |

| Sex | 7 male | 3 female | ||

| Region | South-east (72%) | Elsewhere in England and Wales (28%) | ||

EMT: emergency medical technician; ECA: emergency care assistant

Prevalence of DNACPR forms

Questionnaire respondents were asked how frequently they saw patients with a community DNACPR form. There was a statistically significant increase in frequency noted over time from 0.12 a month (i.e. about once every 8 months) 10 years ago (95% CI [0.09, 0.17]), to 0.40 (about once every 2.5 months) 5 years ago (95% CI [0.30, 0.55]), to today: 3.5 times a month (95% CI [2.7, 4.7]) (Figure 1). The data were aggregated for analysis. The responses of individuals over time were not analysed using repeated measures techniques; it was felt it was reasonable to ignore correlation in responses because there were reasons for variation, such as a change of workplace or role, and a changing level of experience.

Thematic analysis of interviews and relationship to findings

Four themes were identified: challenges in interpreting DNACPR forms and patients' wishes; making clinical judgments; the influence of stakeholders on decision-making; and education.

Challenges in interpreting DNACPR forms and patients' wishes

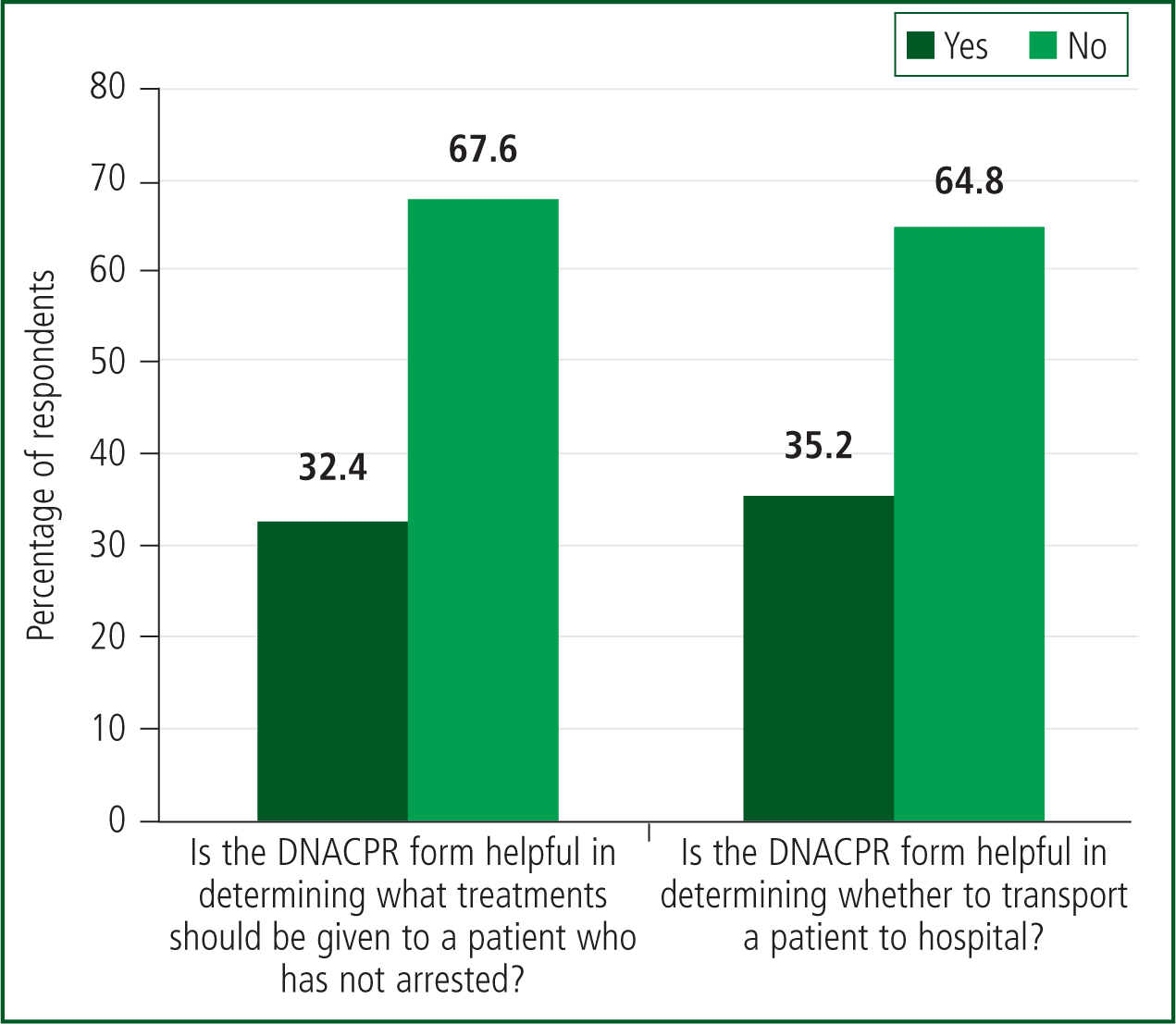

One-third of questionnaire respondents believed that a DNACPR form was helpful in determining whether a patient should be transported to hospital and what treatments should be given to a patient who had not arrested (Figure 2). Respondents reported that the main reasons for calls to patients with a DNACPR in place were relative anxiety (48%), transfer to hospital (34%), provision of comfort care (12%) and patient anxiety (6%).

Interview participants agreed that DNACPRs made resuscitation decisions much easier and allowed them to consider options other than taking the patient to hospital. Yet, at times, there was uncertainty concerning how a DNACPR form affects other aspects of care:

‘Some paramedics on crews won't treat people aggressively if they've got a DNACPR in place. Others will say “do not attempt resuscitation”–it's not “do not treat this pneumonia”.’

Incomplete information added to ‘an already stressful situation’, leaving ambulance clinicians hesitant to make decisions and uncertain whether their decisions were in the patient's best interests:

‘In an end-of-life situation, it would make me ask the question, “what does the patient want?” … We're not quite getting it right, but is that because it doesn't say on the DNACPR, “I don't want to be transported to hospital, I want to die at home”?’

Making clinical judgments

Most questionnaire respondents (86%) had been in situations where they had delivered CPR but wished that they had not; most (72%) also had been in a situation where they wished a DNACPR form had been in place.

Qualitative responses showed how ambulance clinicians felt under pressure from relatives, at times performing CPR in the knowledge that survival was improbable and could go against the patient's wishes:

‘It's just easier to just start 20 minutes, do what you have to do, fill out the paperwork you have to do rather than not starting and then the family kicking up a fuss.’

This participant described concerns about the legal implications of their decisions, fearing complaints if they went against a relative's wishes:

‘Being slightly brutal, I need to protect myself and, if I stopped and a relative made a complaint and said, “Why didn't you carry on?”, then I think from that respect I'd probably do everything I can.’

Influence of clinical stakeholders on decision making

The ambulance clinicians spoke of their experiences with stakeholders, including general practitioners (GPs), care home staff and accident and emergency (A&E) staff. Conflict between professionals was frequent and resulted in competing interests requiring negotiation:

‘GPs I find really obstructive with DNACPRs. I went to a patient who had cancer […] He'd had a sudden decline … I went to the GP … and said: “You need to go and see this chap, I think he's going to die today, so you need to get around and do a DNACPR.” And the GP was like: “Oh I don't like those conversations.”’

Many of the participants struggled with the ‘snapshot’ approach to DNACPR decision-making in A&E departments and described a perceived lack of willingness to continue resuscitation:

‘Well, quite a lot of the time you think, oh well, why are we doing this? And then, all of a sudden, you'll get a return of circulation. But I think the heart-breaking thing is, you put in all that work, and then you think, “oh, I've got to take them to hospital” … and they just look at you as if to say what the hell, and then they sign the DNACPR form in resus.’

Most participants raised concerns about variations between care/nursing homes. These ranged from awareness of issues relating to end-of-life care at an individual level to inadequate protocols and poor information-sharing systems.

‘Some care homes are quite good. Every person in their care if it's appropriate will have one in place … every folder has got a set place for it right in the front so it's easy for us to see as well, which is brilliant.’

‘Nursing/care homes are appalling. They will only ever produce a photocopy of it with no clue of where the original is and half the time they won't have it … what are we supposed to do?’

Education

Very few interview participants had received formal DNACPR education, learning being largely informal from colleagues or online sources. Differences between the patient's wishes and the training culture led to personal conflict:

‘It's drummed into us from when we do our training that we need to try to preserve life.’

‘They wanted to die in the care home, so we just made them comfortable for 40 minutes and let them slip away. But it was going against all my training and, to me, against the grain to let somebody slip away.’

At the end of the questionnaire, free-text comments were invited in response to: ‘What would you like on a form about resuscitation that would make decisions easier for you?’ Several respondents indicated they would like to have more information on the patient's wishes, more broadly than just CPR.

‘What are the parameters of the DNACPR and what treatment they do want? It should not just be about withholding treatment. It should be about what treatment people want—especially those under end-of-life care for illnesses such as cancer.’

‘Patients' hospital wishes if they become unwell: to stay at home or go to hospital?’

‘Specific treatment that they want withheld or not – IVs [IV management in general, including cannulation], BVM [bag valve mask], intubation, oxygen, pain relief etc. Transport preference—hospice or home treatment.’

In addition—and perhaps unsurprising given the context of the study—there were calls for more education and for a nationwide DNACPR form.

Discussion

The use of DNACPR forms in the community appears to be increasing; this change has been reactive rather than planned, and there are potential problems with a form intended for hospitals being adopted in the community (Freeman et al, 2015).

Prehospital practitioners are sometimes in the invidious position of having to balance the needs of the family with those of a patient who has had a cardiac arrest without clear guidance.

Current education errs on the side of interventions to preserve life, which prehospital practitioners sometimes feel uncomfortable delivering when their clinical judgment suggests that the burden of treatment outweighs any potential benefit.

Education

National education of both healthcare providers and the public is required to ensure that communication around resuscitation and other treatment plans are consistently understood.

This might include policies and procedures that are readily available to staff and the public; education of the public about what outcomes can be expected from treatments (including CPR) in different situations; coordination between stakeholders; and education and training in resuscitation decision-making in health providers' annual updates.

There is no scenario on resuscitation orders in the RCUK advanced or immediate life support courses; perhaps this could be introduced.

Stakeholders' problems with sharing data

Although there are regional examples of a single form being used successfully across many healthcare settings, this is not common, and does not address the problem of patients who move to a new region. Several respondents mentioned the need for a national form. Electronic records or a central repository such as ‘coordinate my care’ (Public Health England, 2015) and other forms of electronic palliative care coordination systems (Petrova et al, 2016) may be useful.

Towards a solution? ReSPECT

The RCUK has led on the development of the Recommended Summary Plan for Emergency Care and Treatment (ReSPECT) (Fritz et al, 2017), a new approach to resuscitation and other treatment decisions.

ReSPECT was designed by multiple stakeholders on behalf of the Resuscitation Council (UK), including ambulance clinicians, to address many of the problems outlined here. ReSPECT puts resuscitation decision-making within a context of overall goals of care, and provides universally recognised documentation of clinical recommendations for an emergency.

It has been made nationally available (www.respectprocess.org.uk) and is being adopted in several regions. A web education application (app) is available to all health professionals on this site, along with other educational resources.

Increase in frequency of use

The study reports a substantial increase over recent years in the number of DNACPR forms being seen by prehospital practitioners. While many of these may have been written in hospitals and transferred with the patient into the community, they are also being started in general practice; some nursing homes now routinely have discussions about resuscitation decisions when residents are admitted (Ampe et al, 2016). The intention is to avoid unwanted or inappropriate resuscitation attempts, and to make conversations about DNACPR with patients and their relatives routine rather than waiting until a patient has deteriorated, when they are often too ill to participate meaningfully in a conversation.

However, there has been a failure to communicate this intention to the public, which has led to concern articulated by some media that ‘asking patients to make such a decision when they may have many years to live will prompt concerns that the NHS is writing them off’ (Borland, 2015).

In several regions, forms have been developed that cross all care settings; treatment escalation plans (Sherman et al, 2017), and the ‘deciding right’ approach in the north-east of England (Regnard et al, 2018) are two examples. Both Wales and Scotland now have national forms, which facilitate their initiation and use outside of hospital.

These initiatives may have led to the significant increase in DNACPRs seen in the community over the past 10 years.

Delivering CPR when practitioners do not want to

Many respondents identified occasions when they wished they had not delivered CPR. Several reported situations where they felt they had to carry out futile CPR, knowing the patient would not receive further efforts at the hospital. Multiple factors influenced decision-making, including the location of the arrest, whether a DNACPR form was available and if it had been discussed with relatives.

Compliance with relatives' wishes over patients has been identified in previous studies (Yayes et al, 2003; Murphy et al, 2016). Family members may have phoned the emergency services for support, often because they were anxious about their relative's symptoms, despite knowing their relative did not want CPR. Once present, service personnel often feel obliged to start CPR, which can be very distressing for all involved. The present study suggests that patients and families are not routinely made aware of the limited information clinicians have access to or the importance of ensuring that the DNACPR form is available when they call an ambulance.

Misinterpretation and education needs

The present findings support the conclusions of others that ambulance clinicians do not feel confident in their knowledge of ethical issues surrounding CPR decisions (Wiese et al, 2011), and education and policy guidance are insufficient (Norby and Nøhr, 2012). The absence of specific training contributed to participants' lack of confidence.

While the majority of participants in this study did not think that the presence of a DNACPR form would affect other treatment for the patient, it was concerning that one-third of questionnaire respondents conflated a DNACPR decision with other medical decisions; this was also reported in the interview data, where participants reported that other ambulance practitioners misinterpreted DNACPR to mean ‘do not treat’. Part of the reason for this reported and observed misinterpretation of the specificity of DNACPRs may be because fewer than half of respondents reported receiving any formal education on resuscitation orders.

Limitations

The questionnaire was not extensively validated; however, the potential to elaborate with free-text boxes allowed respondents to add nuance to their answers.

The nature of the recruitment for the questionnaire (at a conference) and for interviews (via flyers) means that there was likely to have been a selection bias towards those interested in education and resuscitation; it is likely that these results overestimate the level of understanding about and education on resuscitation decisions.

The interview sample was not geographically representative, with all participants coming from one ambulance trust. A higher proportion of questionnaire participants came from south-east England. In Scotland, there is a national approach to resuscitation decisions; and in the north-east, the ‘deciding right’ approach encourages more advance care documentation.

Conclusions

The findings of the current study highlight how resuscitation decision making—from the initial conversation to ensuring smooth implementation across care settings—involves a series of complex tasks. Each task requires appropriate training to ensure resuscitation decisions are appropriately communicated and implemented.

The current study identifies a need for education about resuscitation recommendations to be integrated into the training of all prehospital workers, and highlights the need for a national approach to resuscitation decisions and their documentation.