Sepsis is a critical complication of an infection, which, if left untreated, can lead to death. In its advanced stage, as a result of an organism's response to an infection, it damages tissues and organs. In further stages, sepsis can lead to septic shock, with the patient subsequently deteriorating into multiple organ failure (Qureshi and Rajah, 2008; UK Sepsis Trust, 2019a).

In the UK, sepsis has a mortality rate of 40%, contributing to the deaths of 44 000 individuals a year. This is higher than deaths from bowel, prostate and breast cancer combined (UK Sepsis Trust, 2019a). This percentage has been shown to be halved if the appropriate care bundle, known as the Sepsis Six, is delivered within 1 hour of severe sepsis being recognised (Steinmo et al, 2016).

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2017; 1.6.1) states that broad spectrum antibiotics should be administered within 1 hour of identifying that the patient meets the high-risk criteria. It is suggested by Chamberlain (2009) that prehospital delivery of antibiotics shortens length of stay in the intensive care unit and also lowers mortality rates. Further to this, Daniels et al (2015) argue that in areas where the ambulance conveyance time exceeds 1 hour, it is logical that recognising and treating sepsis in the prehospital setting will save more lives than alerting the hospital and undertaking a time-critical transfer.

Kumar et al (2006) highlighted the impact of a delay in antibiotic administration; they reported that in the advanced stages of sepsis, each hour of delay in intravenous antibiotic administration can be associated with an average increase in mortality of 7.6%.

Paramedics are often the first to recognise sepsis and intervene in the community (UK Sepsis Trust and College of Paramedics, 2016), yet both the evidence base and the treatment available in the UK for prehospital sepsis are limited.

However, Pike et al (2015) carried out a study involving paramedics collecting blood cultures, recognising sepsis in two patient groups and administrating IV antibiotics in the prehospital setting in the UK. Their work showed that paramedics could successfully diagnose and treat sepsis. Indeed, 93% of cases were confirmed by hospital medical consultants, and they concluded that paramedics were capable of delivering the care required to patients with sepsis in a timely manner. This is arguably the most promising study because it provides evidence that paramedics are capable of being further involved in prehospital treatment of sepsis.

A comprehensive literature review suggests that there are no UK studies that investigate the effectiveness of IV antibiotics in the treatment of prehospital sepsis nor publications related to the policy of ambulance services regarding this form of sepsis treatment.

It could be speculated whether paramedics would be in a position to reduce the number of deaths by treating sepsis earlier.

Aim and objectives

The aim of this study was to illuminate the views of medical directors in NHS ambulance services, associated with the use of IV antibiotics to treat prehospital sepsis.

This aim was achieved by conducting semi-structured interviews, which were transcribed and thematically analysed to produce the themes that arise from the data collected.

Methods

Design

The study is designed according to the principles of grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss, 1967). Qualitative research focuses on the beliefs, experiences and interpretations of participants, which are crucial for this study's aim to reveal the perceptions of participants themselves. It does this by encouraging participants to use the richness of their own words to explore and describe their experiences in relation to the research question.

This approach involves a cyclical process of collecting data, analysis and developing a coding scheme, followed by further analysis and investigating the emerging theory until a point of saturation is reached where no new constructs are emerging (Green and Thorogood, 2018).

An interpretivist framework (known as the constructivist perspective) was followed, where the researcher believes that there is no singular, objective reality and every individual perceives the world—or in this case an intervention—based on their personal experiences (Bergin, 2018: 18). This approach is most suited to the nature of this study, where the researchers aimed to illuminate the personal views and beliefs of the participants.

Semi-structured telephone interviews were completed to collect the data. Semi-structured interviews involve asking a list of questions but allow the facilitator to explore the topics in greater depth (Bergin, 2018: 132). The qualitative design of the study was deemed most appropriate to produce a meaningful, rich description of the views of ambulance service medical directors regarding the use of IV antibiotics to treat sepsis in the prehospital setting.

Ethical approval

This study received a favourable opinion from the University of Portsmouth science ethics committee; the reference number is SFEC 2018-055.

Sample

Purposive sampling was used. This is a non-probability sampling method, where participants are selected according to the judgment of the researcher (Dudovskiy, 2018). This method was used as the researcher was interested in the views of experts and lead decision makers for the organisation.

The inclusion criteria were purposely narrow. This was because the participants targeted, by virtue of their position, were the only appropriate representatives of the organisations who would be able to provide answers to the questions asked.

Recruitment

Medical directors from all 14 UK NHS ambulance services were approached to participate in the study. Following informed consent, telephone interviews were scheduled.

Setting

All interviews were completed over the telephone, at a time and venue suitable for participants, usually their workplace. These arrangements were accommodated so participants could choose the most appropriate time and place to take the call, where they could feel free to express their opinions in strict confidence.

Positionality

Positionality is a concern in qualitative research in relation to methods of collecting data. Davies (2018) questioned how the position of a researcher influences how they interpret and interrogate findings.

The chief investigator disclosed their role as a paramedic and lecturer to the participants and, despite being involved in current practice in paramedicine, made a conscious effort to bracket any preconceptions related to the research question they may have had.

Data were collected and analysed through the process of reflexivity, where the researcher continuously critically reflects on their own biases and assumptions throughout the research process and how these influence the overall study (Mills et al, 2010).

Data collection

All telephone interviews were completed by the same researcher. Each interview started with a reminder of confidentiality, the purpose of the study and the maximum duration of the interview.

Before interviews started, all participants had an opportunity to ask any questions. At the end of the interview, they were given the same opportunity again. A topic guide was used to ensure all participants had the same experience and for fairness and consistency of data collection.

No participants indicated that they had not understood any of the questions and there was no necessity to clarify anything before or after the questions were asked. All participants were given enough time to give exhaustive answers, and were asked after giving these responses: ‘Is there anything else you would like to add?’ and ‘Are you happy to move on to the next question?’

Data recording and handling

All interviews were recorded using the University of Portsmouth's Cisco telephone network. The audio files were downloaded in wave audio format (WAV) immediately after each interview and stored on a password-protected Google Drive managed by the university.

Audio recordings of each interview were transcribed by an independent transcription service, using a smart verbatim style, and subsequently prepared for coding.

Data analysis

The transcribed interviews were subjected to a process of thematic analysis applying the principles of Glaser and Strauss's (1967) grounded theory. These approaches are recognised ways to elicit answers to questions from groups of respondents and they aim to reduce the complexity of participants' accounts by searching for patterns in the data.

The process involved immersion in the data, identification of patterns, coding the data and organising them and then reporting on the findings with the use of direct quotations (Green and Thorogood 2018: 258).

Results

Five telephone interviews were conducted and no participant withdrew their consent or any data they disclosed during interviews. Each interviewee was assigned a number for data analysis and manuscript writing.

Codes

The analysis produced 24 meaningful units in the data. These units were given five distinct codes. Coding is a process of applying descriptive labels to a qualitative dataset to illuminate key themes within it. This process helps researchers to elicit the raw data from the textual or visual evidence collected.

One negative case was identified during the analysis. A negative case is characterised by respondents' experiences or viewpoints differing from the main body of evidence and often, it is believed, these cases strengthen the theory (Hsuing, 2018). The negative case identified a positive belief in contrast to the majority of negative examples for the given code.

In this case, the code ‘Standardisation of equipment and protocols’ covered numerous responses regarding the need to agree on one drug being a potential barrier. However, the following response highlighted that there could be a positive solution with an existing pharmaceutical intervention available to all paramedics in the UK:

‘The paramedics already have access to benzylpenicillin, purely for meningitis. We took microbiological advice regarding the management of septic patients, and whether we wanted to introduce a wider spectrum of antibiotics. The conclusion was that we're probably better off sticking with one, because various different units have various different ideas on what the firstline empirical antibiotic would be, and benzylpenicillin is as good as any other.’

Themes

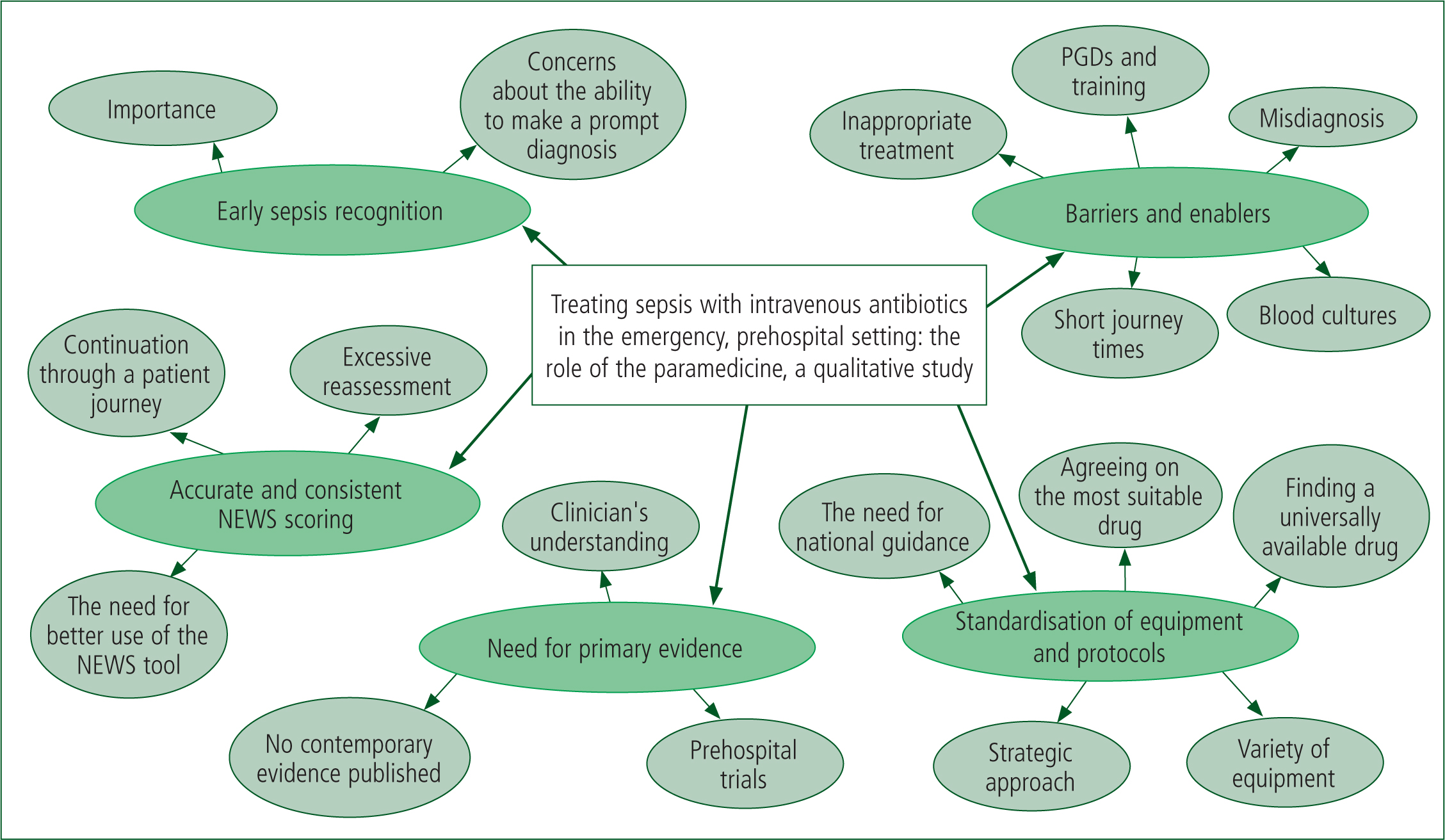

The five codes were converted into the following themes: barriers and enablers; early sepsis recognition; accurate and consistent National Early Warning Scores (NEWS) scoring; the need for primary evidence; and standardisation of equipment and protocols. These themes and their corresponding codes are shown in Table 1.

| Theme | Supporting codes |

|---|---|

| Barriers and enablers | Blood cultures, starting inappropriate treatment, developing patient group directions and training, short distances between patients and hospitals, misdiagnosis |

| Early sepsis recognition | Importance of early recognition, reservations about the current ability to recognise sepsis promptly |

| Accurate and consistent National Early Warning Score (NEWS) scoring | GP through to hospital admission continuation, excessive reassessment at different levels, Better use of NEWS/NEWS2 tool |

| Need for primary evidence | Clinician's understanding of what they are doing, collecting prehospital data, unproven, research needed |

| Standardisation of equipment and protocols | Variety of equipment, finding a drug that is available to all, agreeing on the same drug, need for national guidance, strategic approach |

Description of the themes

Summary

Each of the themes represents the opinions of the medical directors interviewed. A number of differences, depending on their specialty of medicine, were reported.

At one end of the spectrum were concerns about potentially unnecessary use of IV antibiotics if it was not possible to test blood culture in the ambulance service. However, the analysis also found that where there was compelling evidence for the efficacy of the intervention, specifically where long transfer distances may be necessary, this treatment option could be explored in more depth.

Five dominating themes were developed; these are analysed below and illustrated with direct quotes from the data. Figure 1 is a visual representation of the themes and codes developed in the form of a mind map.

Barriers and enablers

This theme reflects participants' concerns and potential enablers associated with the IV antibiotic therapy being made available to prehospital emergency clinicians for the treatment of sepsis.

Most participants suggested that to consider this intervention, they would be reassured if microbial results could be made available to identify the pathogen causing sepsis before treatment was started:

‘I think where ambulance services have got short running times to hospital, then there is an advantage in being able to do blood cultures prior to giving antibiotics. I think the likelihood of getting really solid blood cultures in prehospital care is not great. I think it's a lot easier to do in a hospital environment.’

Some participants were concerned about not tailoring the treatment and starting an inappropriate drug regimen without access to medical records, which are available to physicians in emergency departments.

Additionally, there were concerns about identifying a drug that is effective and easy to constitute and administer, given the nature of prehospital settings:

‘When I'm sitting in the emergency department, I have an integrated prescribing care record. So, as the patient comes in, I know all the drugs the GP gives them, I know all the drugs they've been given in the nursing home recently, and their last dose of everything. I know all their allergies. I also know their risks much more comprehensively than the history for many of my patients.

‘Now, we can't give the paramedics gentamicin, because they don't know the renal function of these patients, etcetera, they can't load it. So, we've got to give them something very basic that they can load up really quickly, and it's got to cover Gram-negative sepsis. So, it's got to cover the things that slip through the net for us. So, how are we going to decide what the right antibiotic is? And the only way I can see that being done, and the way it's done in other ambulance services, is either give something specific for the obvious, or something very, very broad spectrum for the possible.’

A further barrier has been identified to support the above concerns; the question of a possible misdiagnosis of sepsis and its consequent treatment with IV antibiotics was raised:

‘Again, you've got to make sure we're clear on what we're treating. I went out with a crew recently, and we had a patient who was dehydrated, hypotensive, tachycardic, who also had a fever. He wasn't septic, he was able to walk around and mobilise without any difficulty at all, and didn't really fit the full criteria for sepsis but, if you just looked at NEWS scoring, and the fact that he had a fever, it would suggest that he did in fact have sepsis.’

At the same time, the majority of participants recognised the need for early IV antibiotic administration for sepsis. Some acknowledged that, where there are significant transfer delays or where further testing was be available, prehospital sepsis care could be progressed, particularly with the use of advanced paramedics. One participant felt strongly about this intervention being delivered in a prehospital arena:

‘You've got to start antimicrobial therapy as quickly as possible in sepsis, to try and stop it becoming fulminant, so as early as possible intervention is vital. So the first dose of antibiotics should be given in the prehospital environment.’

‘If the delay was hours, so either we've spent too long trying to get to the patient, because of geography or other reasons, or we've spent too long transferring the patient, because of geography or other reasons, working out a method with the system to give antibiotics earlier to the appropriate patient is entirely appropriate.’

‘I think the opportunities in the future that I would like to see would be access to near patient testing, including lactate assay, which would clearly strengthen the recognition of the sepsis six, accepting that two of them historically have only been able to be established once the patient has arrived in hospital, with access to blood work …

‘Some of the enablers around that would be access, perhaps for our specialist paramedics or advanced paramedics who are now increasingly based [with] and providing support to clinical teams of ambulance clinicians.’

Early sepsis recognition

This theme is related to the emphasis the participants put on early recognition of sepsis, using sepsis recognition tools and pre-alerts to aid hospitals prepare before the patient reaches the emergency department. It was noted by several that it was important not to cause any additional on-scene delays once sepsis is suspected:

‘We already have a set of pre-agreed criteria for pre-alerting all emergency departments to the impending arrival of a patient with a presumed diagnosis of sepsis. We recognise that, actually, it's important that patients aren't delayed at scene, waiting for an advanced paramedic, particularly if that care can be escalated and delivered on arrival in hospital.’

‘Early resuscitation of very sick patients, spotting a deteriorating patient and resuscitating them, without a doubt, is very important, and making the people when you arrive as a trusted assessor aware that you're highly suspicious.’

It was also suggested that the ability to administer prehospital IV antibiotics would not necessarily be a viable way to reduce the time from sepsis recognition to antimicrobial treatment being administered and the majority would welcome good-quality pre-alerts.

The interviewer cited retrospective, published data showing delays in hospital administration of antibiotics while exploring this point with one of the participants:

‘But to argue that because the hospitals are rubbish we should give the antibiotics, I don't support that argument. If we pre-alert correctly and we do our bit correctly, and we spot a deteriorating patient correctly, and we don't over pre-alert, then that is the hospital's business to do that.’

Accurate and consistent NEWS scoring

A high proportion of participants said it was necessary to collect NEWS scores frequently and consistently to spot the deteriorating patient early:

‘One of my concerns is that we are collecting data for NEWS scores, but it's not until the patient actually gets to hospital that it starts to be documented and then followed up. So that you then get the first three readings, and the trend line developing in the first 3 hours of attendance in hospital, whereas the patient may have had an initial assessment by a general practitioner, then an ambulance assessment, and actually he may already have three points of data at the point of reaching hospital. Then you should be onto it, and start treatment at a very early stage. So I think there is already something that could be done to bring that forward if we have better use of NEWS scoring.’

The value of recognition tools was emphasised, as was the importance of not causing additional on-scene delays:

‘To help our staff recognise sepsis, you will recognise a number of the algorithms that we've produced to support staff. Additionally, we've issued a further update recently about the value of National Early Warning Scores. About the importance, if feasible, of establishing intravenous access, but not to delay on-scene times to achieve that.’

Standardisation of equipment and protocols

An almost universal theme among all interviewees was the challenge of standardising the drug of choice, along with the difficulties of using the same equipment for microbiological testing, which would also have to be compatible with all the labs in hospital trusts in the areas where ambulance services operate.

It was also speculated that developing patient group directions and training the workforce to deliver them could be problematic. Participants suggested this would be more likely achieved by having specialist paramedics as the clinicians who could deliver IV antibiotics in the prehospital arena:

‘The practical issue is that we would need patient group directions for intravenous antibiotics to be used by paramedics. And the whole process of not just agreeing patient group directions but also training on them is quite a significant burden for ambulance services if you were going to do it for all paramedics. If you were going to do it for your specialist cohort of paramedics, that's a different matter.’

Need for primary evidence

This was the least surprising theme to emerge during data analysis. A number of opinions were expressed regarding the need for evidence of the efficacy of paramedics administering prehospital IV antibiotics for sepsis.

If a patient has been given broad-spectrum antibiotics, it could be very difficult to identify the specific pathogen causing the infection in hospital. National support would be needed for the intervention.

In addition, an internal study at one of the participant's trusts found high sensitivity but only approximately 30% specificity when detecting prehospital sepsis.

One interviewee considered there was a possible argument in favour of the intervention in remote areas with a long transfer time as it could reduce the time between the onset of sepsis and antibiotic administration:

‘I'd like to see some data on the benefits of prehospital antibiotic usage. My concern would be the risk that we may add into the system about actually treating with an inappropriate antibiotic, which then actually delays or causes increasing morbidity or mortality.’

‘I think all of this stuff needs to be studied, and I think more and more we need to be starting to look at ourselves as part of a system. So I do support research and an evidence-based approach to prehospital improved care, which does include giving antibiotics early. But it's just how you get there.’

Discussion

This study was qualitative as its aim was to ask key personnel about their views on the possible use of prehospital IV antibiotics for the treatment of sepsis. Semi-structured telephone interviews were carried out; these were deemed the most suitable way of collecting data in this study as they would be able to capture the participants' true feelings and views.

This study identified a number of themes and provided evidence never published in the UK on the opinions of a number of medical directors' regarding the use of IV antibiotics in prehospital emergency care.

The most dominant theme was the desire for a national drive to accurately and consistently use the NEWS/NEWS2 scoring tools to standardise how all health professionals record and score a level of patients' deterioration.

Following the interviews, it became evident that treatment of prehospital sepsis is high on the agenda of the chief clinical decision-makers interviewed and a number of opportunities have been identified.

Pike et al (2015) evidenced paramedics' ability to aseptically collect prehospital blood cultures, accurately identify sepsis and start the appropriate treatment in a timely manner. However, the evidence gathered here suggests it may be difficult to reach a national agreement and approach to the use of emergency prehospital IV antibiotics for sepsis, because of a general inability to analyse blood cultures outside a hospital setting. This is further complicated by variations in equipment used by emergency services, hospitals and microbiology labs.

The important theme may be the interest in the evidence for the effectiveness of the proposed out-of-hospital intervention, which is lacking in the UK. This is underlined by the call for research from NICE (2017), which would increase understanding of the effectiveness of current approaches to the treatment of sepsis. There evidently is a significant interest in studying such data to help inform current protocols as well as key decision-makers and stakeholders.

Following a literature review, only one appropriate study was found. Alam et al (2017) suggested that prehospital administration of IV antibiotics to patients with sepsis has no benefits in the context of mortality 28 days later. However, this study was not based in the UK, largely looked at patients in urban areas and was in a different healthcare system. Therefore, it could be argued that it does not carry a representative result for the British health service and population.

The NICE (2017)Sepsis Recognition, Diagnosis and Early Management clinical guideline, which is the most contemporary approved clinical practice publication, recommends further research and a comprehensive service evaluation of the NICE sepsis guidelines.

It could be argued that the effectiveness of the current approach is not fully understood. This is particularly of interest to the authors, as the NICE (2017) guideline at 1.7.3 advises that ambulance services should have mechanisms in place to give antibiotics to high-risk patients in prehospital settings where the transfer time is more than 1 hour. No published evidence has been found to date regarding transfer times across the UK for patients with sepsis, or how long it takes to extricate these patients, which adds to the transfer time and risks breaching the 1 hour recommendation within which antimicrobial treatment should be started.

On the other hand, in this study, a lot of emphasis was placed on rapid transfers where possible, with a pre-alerting system and sepsis recognition tools being used. These were reinforced by the importance of and a drive to use NEWS/NEWS2 scoring to improve emergency sepsis care. This finding links to the drive and recommendations from the UK Sepsis Trust (2019b) on how health professionals can spot sepsis more effectively, adding value and reassurance that ambulance services are already following the national recommendations to help recognise sepsis rapidly.

Additionally, approaches in different parts of the country are, inevitably, influenced by the experience and position of their respective medical directors, who review and endorse all clinical activities allowed in the services they oversee. While a number of themes were identified, responses ranged from being cautious about this pharmacological approach to a belief that an appropriate drug was already in possession of frontline ambulances, believed to carry little risk and potential significant benefits, which could be used.

It could be concluded from the data analysis in this study that current protocols for the treatment of sepsis in the UK ambulance services are largely influenced by multiple considerations but, in the end, expert opinion and experience differ across the ambulance services. Equally, it is possible that the findings presented and discussed here can be accounted for by the methodological considerations discussed below.

Methodological considerations

Although data saturation was reached with this sample, the results do not represent the saturation of data regarding the research question. This is because, although the purposive sampling was employed, not all UK medical directors contributed to the study.

In addition, because participants were from a variety of medical disciplines, they may have different experiences of treating sepsis. A possible solution could be grouping the respondents into the specialty of the profession they represent and conducting an analysis within these groups. The responses could further explain why particular groups feel strongly about something that others may not consider and vice versa.

Another problem in relation to validity was that only medical directors were interviewed for the purpose of this study and the results are based on their individual perceptions and beliefs. During the analysis, it became evident that a consideration of treating sepsis in the ambulance service with IV antibiotics would also have to involve microbiologists, paramedics, pharmacists and, indeed, patients. Given this limitation, it could be proposed that all these groups should be interviewed to gain a fairer view from the experience of all involved in the process, rather than just ambulance service medical directors.

With regard to the telephone interviews themselves, it is noteworthy that asking respondents for their views and opinions where the loss of participant anonymity is inevitable has the potential for information to be withheld or biased towards perceived expectations (Farnsworth, 2016).

Conclusion

Sepsis care in the majority of the UK ambulance services is fairly basic. The published evidence is limited, and what is available is largely quantitative in design. Therefore, this study provides valuable new information in the field of prehospital sepsis care.

The results of this study suggest that, although common beliefs exist within the population interviewed, opinions differ. Current prehospital treatment for sepsis in UK ambulance services ranges from the conservative administration of sodium chloride and oxygen to collecting blood cultures and administering IV antibiotics. Indeed, many key decision-makers have a particular interest in exploring advanced approaches to sepsis treatment; at the same time, they are seeking evidence for the efficacy of the use of IV antibiotics to treat sepsis in emergency prehospital care in the UK.

The authors therefore propose a large, double-blind, randomised controlled trial should be carried out in the UK to investigate the efficacy of IV antibiotics in prehospital sepsis because of the lack of quantitative evidence of this nature.