In the Australian context paramedic and nurse education has followed a similar path over the last two decades, moving away from work based training models to pre-employment university–based models where graduates are required to complete a graduate year in the field prior to being given an authority to practice ( Joyce et al. 2009). They also share core curricula, which has led to many Australian universities offering a double nursing/paramedic degree. Paramedics and nurses operate in highly charged, complex and emotionally driven situations on a daily basis—and while a high degree of clinical knowledge and skill is imperative, these skills and knowledge are not displayed in isolation. They involve individuals with differing needs, expectations, perspectives and requirements.

A nurse or paramedic treating a patient with chest pain for example, will have to treat the patient's emotional state and address their fears, concerns and apprehension in addition to treating their physical pain. While definitions and explanations of interpersonal skills vary, they share common threads. They are significantly linked to human interaction and contribute substantially to establishing a high quality caring relationship with patients. Duffy et al (2004) describe interpersonal skills as:

‘…inherently relational and process oriented; they are the effect communication has on another person such as relieving anxiety or establishing a trusting relationship…’

Goleman (2006) uses the term ‘social intelligence’ to refer to our ability to ‘act wisely in human relationships’. He divides social intelligence into two capabilities; ‘social awareness’, which refers to skills in empathy, attuning to a person, understanding another's thoughts, feelings and intentions and knowing how the social world works, and ‘social facility’, which refers to interacting smoothly at the non-verbal level, self-presentation, influence and concern.

Key stakeholders in Australia recently recognised that although paramedic graduates clinical skills were adequate, a deficit existed in the area of interpersonal relationships with particular demographics of patients, co-workers and superiors (Lazarsfeld-Jensen, 2010).

A network of key stakeholders funded by the Australian Learning and Teaching Council found that Australian paramedic undergraduates have limited knowledge of the diverse communities they work within and suggested a much greater emphasis on the teaching of complex interpersonal, ethical and professional skills is necessary at university (Willis, 2009).

A UK study found that undergraduate paramedics felt their communication and interpersonal skills required further development and that they often felt ill-equipped to engage constructively and confidently with patients (Donaghy, 2010). Likewise, literature suggests that nursing graduates do not communicate effectively with patients, colleagues or other health professionals and that patients’ are dissatisfied with this (Ashmore and Banks, 2004).

Harrison and Fopma-Loy (2010) discussed a mounting frustration with student nurses displaying a ‘disconnection’ from patients overlooking the human being they are caring for. Highly-developed interpersonal skills are an important component of health professional competence, and are therefore considered mandatory for any graduate entering the nursing and paramedic professions (Sparks et al, 1980).

The Council of Ambulance Authorities (CAA), the peak body representing the principal statutory providers of ambulance services in Australia, New Zealand and Papua New Guinea, produced Paramedic Professional Competency Standards stating that a competent paramedic ‘uses interpersonal skills to encourage the active participation of patients’ (Council of Ambulance Authorities, 2010). Accordingly, interpersonal skills are routinely listed in position descriptions by prospective employers who are looking for individuals who can display not only clinical, but social competence. The Australian Nursing Federation (2005) includes ‘a demonstrated effectiveness in communication and interpersonal skills’ as one of the selection criteria for enrolled nurses, and the UK Nursing and Midwifery Council (2010) lists communication interpersonal skills as one of its four key domains.

Given the importance of interpersonal skills this review aims to determine what teaching techniques/methods are being used to teach undergraduate nurses’ and paramedics’ interpersonal skills and how effective they are.

Methods

Search Strategy

On 13 September 2012, the search strategy outlined in Table 1 was performed to recover relevant articles. The search was conducted using electronic databases, Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and ERIC. It was limited to journal articles published from 2000 onwards, as studies prior to this were deemed to have limited relevance to the current curricula.

| Population (subject headings): | Intervention (subject headings): | Outcome (subject headings): |

|---|---|---|

| Emergency medical service, emergency treatment, emergency medicine, ambulances, air ambulance, first aid, military medicine. | Education, training, teaching, curriculum. | Communication |

| Population (key words): | Intervention (key words): | Outcome (key words): |

| Prehospital, pre-hospital, paramedic*, ambulance*, out-of-hospital, “out of hospital”, ems, emt, “emergency services”, “emergency medical service*”, “emergency technician”, “emergency practitioner”, “emergency dispatch*”, “first responder*”, “public access defibrillation”, “emergency rescue, emergency resus”, “emergency triage”, “advanced life support”, “community support co-ordinator”, “community support coordinator”, “emergency care practitioner”, “extended care practitioner”, “physician assistant” | Educat*, train*, teach*, course*, degree*, program*, curriculum | “Interpersonal skills”, “people skills”, “nontechnical skills”, “nontechnical skills”, “social intelligence”, “emotional intelligence” |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

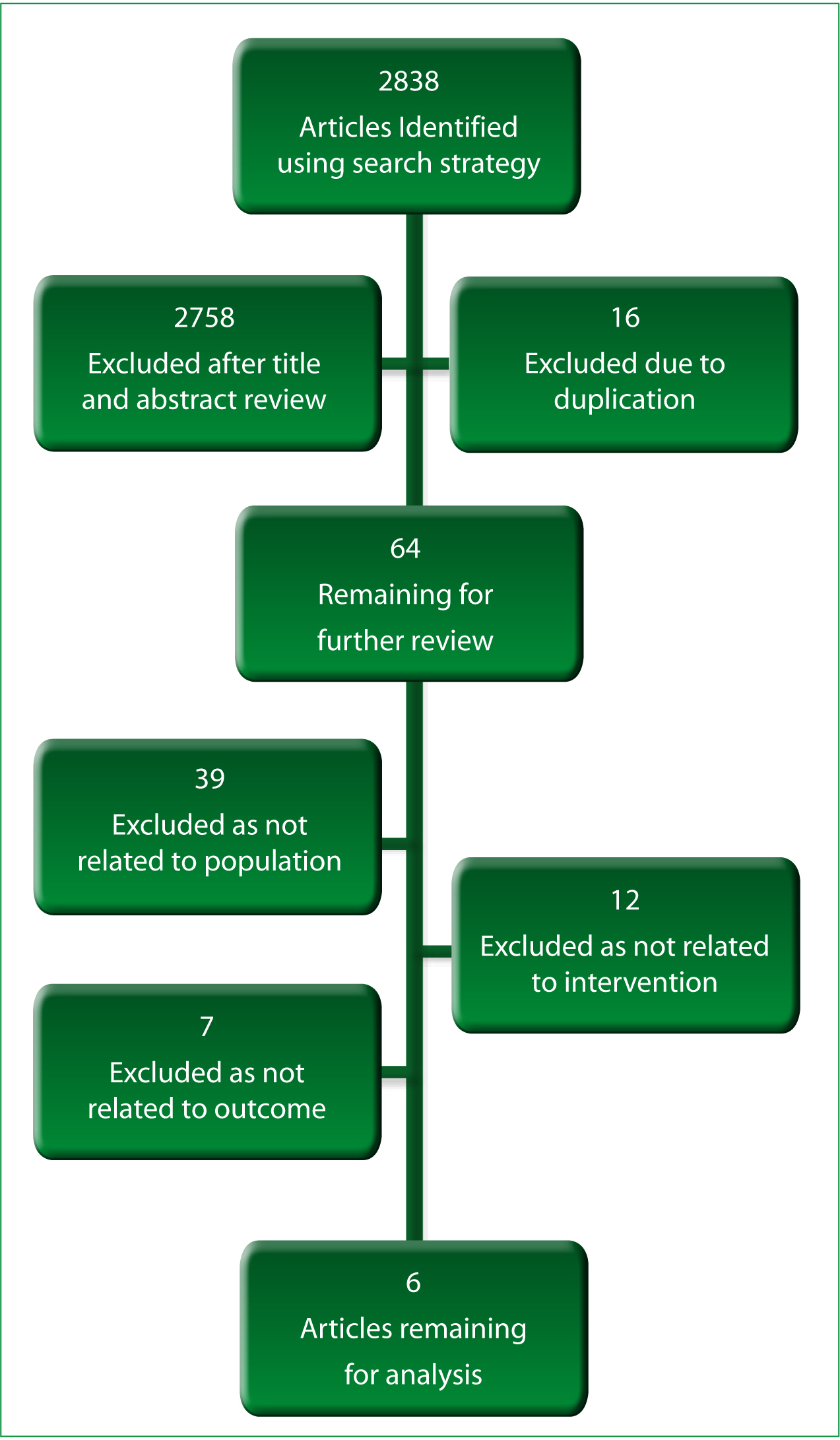

The search yielded a total of 2838 articles which were reduced to 64 following a title and abstract review and the removal of duplicates. Six of those articles were considered relevant based on the inclusion criteria listed in Table 2. A hand search of the reference lists yielded no more new articles. The search strategy results and application of these criteria can be seen in Figure 1.

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Articles relating to paramedics, EMT's (or similar) and nurses. | Articles relating to other health care professions such as dentists or physiotherapists, etc. |

| Intervention | Articles discussing undergraduate education, training, programmes or courses. | Articles discussing post graduate or workplace based training or education. |

| Outcome | Articles investigating interpersonal skills, people skills, soft skills or non-technical skills. | Articles investigating clinical or technical skills. |

Data extraction

Data was extracted from the articles and documented in table form under the following headings, ‘study author’ and ‘year, country of origin’, ‘population’, ‘study summary’, ‘teaching tool’ and ‘best evidence medical education’ (BEME) Quality Grading and Outcomes’. Table 3 presents a summary of the data extracted from the seven identified articles.

| Quality indicator | Detail |

|---|---|

| Research question | Is the research question(s) or hypothesis clearly stated? |

| Study subjects | Is the subject group appropriate for the study being carried out (number, characteristics, selection, and homogeneity)? |

| Data collection methods | Are the methods used (qualitative or quantitative) reliable and valid for the research question and context? |

| Completeness of data | Have subjects dropped out? Is the attrition rate less than 50 %? For questionnaire based studies, is the response rate acceptable (60 % or above)? |

| Control for confounding | Have multiple factors/variables been removed or accounted for where possible? |

| Analysis of results | Are the statistical or other methods of results analysis used appropriate? |

| Conclusions | Is it clear that the data justify the conclusions drawn? |

| Reproducibility | Could the study be repeated by other researchers? |

| Prospective | Does the study look forwards in time (prospective) rather than backwards (retrospective)? |

| Ethical issues | Were all relevant ethical issues addressed? |

| Triangulation | Were the results supported by data from more than one source? |

Quality assessment

The BEME tool, developed by Buckley et al (2009), was used to assess the quality of each study (Table 3). The BEME tool consists of 11 quality indicators related to the appropriateness of the study design, conduct, results analysis and conclusions. The tool gives a rating of ‘higher’ to those studies deemed to have met seven or more of these indicators, and ‘lower’ quality rating to studies meeting less than this amount.

Results

The search strategy did not reveal any studies concerning the teaching of interpersonal skills to undergraduate paramedics. All six studies included in this review examined undergraduate programmes and teaching methodologies designed to enhance student nurse interpersonal skills. The studies were all similar in that they used traditional classroom based interpersonal skills education in combination with an alternate strategy. Each study is discussed below, detailing the educational methods used and the subsequent outcomes.

Online discussion

One of the six studies used online discussion as a teaching tool. This study asserted that nursing education traditionally focuses on knowledge and skill development with minimal focus on the affective component of the profession (Deering and Eichelberger, 2002). It therefore aimed to have students evaluate their own interpersonal styles and provoke a shift in learning to the affective domain of feelings, attitudes, values and opinions.

Students were required to discuss two questions pertaining to their interpersonal skills online among groups of four to five. The students felt the online activity was a good way to evaluate and improve their own interpersonal skills but felt it worked best in combination with other techniques, recognising the importance of face-to-face communication. The study concluded that online discussion was invaluable in improving nursing students’ interpersonal skills.

Despite this however, it lacked vital detail such as participant numbers and demographic, selection criteria, ethics approval and detailed results. In addition there was no triangulation of any additional data using methodologies other than student self-report data to support such a claim. For these reasons the paper was given a ‘lower’ BEME quality rating and the purported conclusions could not be considered sound.

Service learning

Two studies engaged students in service-learning projects. These service-learning programmes aimed to develop students’ interpersonal skills and expand their experience by immersing them in community based activities (Bassi, 2005; Purdie et al. 2008). The Bassi (2005) study used the following seven vectors, based on Erikson's developmental theory, to evaluate interpersonal development: competency, autonomy, mature interpersonal relationships, managing emotions, integrity, identity and purpose (Chickering and Reisser, 1993).

The students’ responses suggested growth and development across all seven vectors. They reported feeling better prepared to engage with the community, a great sense of accomplishment and an increase in confidence and personal autonomy. Likewise, in the Purdie et al study (2008), students felt that they had become better listeners and that they were much more confident and relaxed in their interactions with patients as a result. The authors concluded from these results that service learning helps build student skills, knowledge and values in preparation for entering a professional workforce and making a valuable contribution to society.

Audio tapes

This research project was devised to explore nursing students’ communication with patients during assessment interviews, and to evaluate the effectiveness of using tape recordings and transcripts of clinical encounters as a teaching aid in the classroom ( Jones, 2007). A communication analysis of tape recordings and transcripts of student nurse-patient interactions was conducted. The author found that student nurse-patient interactions, contrary to ‘best practice’ recommendations, were ‘task centred and bureaucratically organised’ ( Jones, 2007). The second stage involved using tapes and transcripts of similar interactions as a teaching and learning resource in the classroom. This phase resulted in students being able to identify limitations in communication strategies using a SEGUE framework designed to facilitate the teaching and assessment of communication skills (Makoul, 2002). The students found the use of tapes and transcripts added a heightened sense of realism to the session and that it also increased reflection upon and self-awareness of their own interpersonal skills. The author concluded that the use of tape recordings as a resource for teaching and learning interpersonal skills is very worthwhile. They also reflected that this does not necessarily translate to communication on the ward as a ‘hidden curriculum’, such as socialisation and workplace practice may influence their performance ( Jones, 2007).

| Study author and year | County of origin | Population | Study summary | Teaching tool | BEME quality grading | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bassi, 2005 | USA | 18 third year undergraduate nursing students | Pilot community project, with structured reflection | Service-learning | Higher | Improved confidence and preparedness for working within the community. |

| Deering and Eichelberger, 2002 | USA | Unknown number of Baccalaureate and Bachelor of Science in nursing students | Online discussion groups to increase awareness of, and improve interpersonal skills | Onlinediscussiongroups | Lower | Students were able to speak more freely in the online setting and gained valuable insight into their own skill level. |

| Jones, 2007 | UK | Ten third year adult nursing degree students | Assessment ofnurse-patientencounters | Audio tapes of nurse-patient encounters | Higher | The use of tapes added valuable realism to the discussions, and increased self-reflection and awareness. |

| Pearson and McLafferty, 2011 | UK | 187/216 final year diploma of adult nursing students | Simulation assessment re-focused on nontechnical skills | Role play/ simulation | Higher | Valuable learning experience improving communication, team work, leadership, organisation and decision making skills. |

| Perry and Linsley, 2005 | UK | 36 second year mental health nursing students | Role play used to assess interpersonal skills | Role play | Higher | Teaching and assessment methods were positively evaluated by students. |

| Purdie et al. 2008 | UK | Six third year nursing students | A seven day community charity placement | Service-learning | Higher | Improved confidence and preparedness for working within the community. |

Role play

Two of the studies used clinical role play and simulation to teach and assess interpersonal skills (Perry and Linsley, 2006; Pearson and McLafferty, 2011). The study by Perry and Linsley (2006) used a nominal group technique to have students participating in the study evaluate the effectiveness of the assessment.

The evaluations identified five key themes; role play, marking, course content, teaching style and user involvement. Contradictory evaluations were given in all five areas. For example, some students thought the role play was realistic due to the use of professional actors and pressure of the assessment mimicked a true working environment, while another student thought the pressure of the situation made it difficult to display her true interpersonal qualities. The contradictory nature of their evaluations made it difficult to definitively conclude anything about the success of role play as a teaching tool for interpersonal skills.

In a study conducted by Pearson and McLafferty (2011), students participated in a simulated ward scenario, having been previously made aware of the non-technical criteria against which they would be assessed. Immediately following the simulation exercise students completed a mixed Likert scale, and closed questions with free text response questionnaire. Overall, 87 % of students found the ward simulation to be a valuable learning experience. The free text responses indicated that the most valuable aspects of the exercise were the use of team work, organisational skills, problem solving and autonomous decision making. They reported that the least valuable aspect of the exercise was the lack of realism in comparison to what actually occurs on the ward. The questionnaires also highlighted learning needs such as communication skills, confidence and assertiveness. The author concluded from the evaluation data that simulation can be an effective tool in the teaching and assessing of non-technical nursing skills, as well as a valuable tool for highlighting learning needs.

Discussion

Each of the studies identified gaps in the required interpersonal skills and those displayed by graduating nurses. Many factors could have contributed to this theory-practice gap including inadequate or lack of interpersonal skills teaching, generational influences, technology, focus on clinical skills, maturity and experience.

Each paper focused on how undergraduate programmes could better prepare the interpersonal skills of their student's. All of the six studies used traditional teaching approaches such as didactic lectures to teach the theory of interpersonal skills in combination with their chosen teaching tool.

The Deering and Eichelberger (2002) and Perry and Linsley (2005) studies supplemented this with videoed nurse patient interactions to increase awareness and foster discussion about interpersonal skills. Three of the studies required students to evaluate the interpersonal skills assessment tool employed (Perry and Linsley, 2005; Jones, 2007; Pearson and McLaffery, 2011.

In Bassi (2011) and Purdie et al (2008), the students discussed what they had gained from participating in the service learning programmes in focus groups and reflective pieces. In each instance this self-reported data indicated the students enjoyed the teaching approach and felt that their interpersonal skills had improved as a result. It would have been valuable to support these results with behavioural evidence of these perceived improvements.

Only one of the six studies actually recorded, analysed and reported on student nurse interpersonal skills during actual patient interactions prior to their intervention ( Jones, 2007). The results indicated that students had difficulty engaging and involving the patient and were predominately focused on systematically gaining the relevant information. Unfortunately this procedure was not repeated after the teaching intervention, with the author relying on student feedback to access learning and improvements in interpersonal skills. In essence, each study reported success to varying degrees following the instigation of their interpersonal skills teaching strategy. Students felt better prepared, more confident and more self-aware of their own interpersonal skills than they did prior to the interventions. It is unclear however from these studies whether that translates to a better display of these skills in the work place and improved patient care.

Conclusions

This systematic review has highlighted the need for undergraduate programmes to place more emphasis on the teaching and learning of interpersonal skills in order to better prepare student nurses and paramedics for the requirements of their profession.

In addition, it has been demonstrated that a wide array of teaching strategies can be employed to achieve this. The most successful methods appeared to use a combination of teaching strategies, and engaged the students in an activity which had as much realism as possible. Similarly the use of evaluation tools in combination with student self-reporting would seem to be the most thorough and accurate way of evaluating such humanistic skills which are more difficult to measure than clinically based skills. Finally this literature review has highlighted the lack of published research into the teaching and development of interpersonal skills in undergraduate paramedic programmes and the necessity for this to occur in the future.