Pain is defined as ‘an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage’ (World Health Organization (WHO), 1986). It can be divided into several classes, with acute pain being commonplace within the prehospital environment.

Acute pain arises abruptly, often secondary to trauma, with trauma defined as ‘physical injury caused by violent or disruptive action’ (Mosby, 2016). Traumatic pain accounts for 35–70% of all prehospital cases of acute pain (Albrecht et al, 2013).

Despite its prevalence, acute pain experienced by trauma patients is greatly undertreated in emergency care (Scholten et al, 2015), with the majority of prehospital patients who experience acute pain still being in pain on admission to the emergency department (ED) (Jennings et al, 2011a). The frequency of acute pain within prehospital trauma patients combined with the pervasiveness of pain undertreatment shows improvements are needed in patient care.

Pain management is a multidimensional construct, consisting of psychological explanation and support, treating underlying conditions, physical methods, e.g. application of splints, burns treatment and haemorrhage control and pharmacological treatment (Association of Ambulance Chief Executives (AACE), 2019).

Not treating prehospital pain is poor medical and ethical practice, with failed pain management constituting medical negligence (Brennan et al, 2007). Additionally, it causes increased sympathetic activity which can contribute to physiological complications (Cox, 2010).

Analgesia can be provided through pharmacological, physical and psychological intervention (Hanson et al, 2017). UK paramedics carry a number of pharmacological analgesics, including paracetamol (oral/intravenous (IV)), ibuprofen (oral), 50% nitrous oxide/50% oxygen gas (Entonox), and morphine (IV/intramuscular/oral) (Hodkinson, 2016).

However, each drug has limitations; morphine has a narrow therapeutic range (Bounes et al, 2011), meaning there is a high risk of accidental overdose causing complications such as hypotension, respiratory depression and loss of protective airway reflexes, which can be especially problematic in haemodynamically unstable patients. Paracetamol treats mild-to-moderate pain, and is most effective when used within a multimodal analgesic approach owing to its opioid-sparing effects (Sharma and Mehta, 2014).

The WHO's analgesic ladder, originally created for cancer pain, has undergone modifications and separates analgesia types into levels based on their efficacy at managing pain levels/scores according to different causes of pain, including acute pain (Anekar and Cascella, 2021). When morphine is contraindicated, paracetamol must be used on its own or in combination with drugs such as Entonox and ibuprofen (when these are not contraindicated). This means pain management is limited to the first step of the analgesic ladder (Vargas-Schaffer, 2010).

Methoxyflurane (Penthrox), an inhalatory analgesic, has recently been trialed and introduced to UK ambulance services as an analgesia for moderate to severe pain. However, it is not commonly used and has not yet been recognised as a useful method of pain relief by all prehospital services (Hospital Healthcare Europe, 2017; Forrest et al, 2019).

Entonox, although fast acting and having few adverse effects, is on the ladder's first step, and contraindications and cautions around its use, prevent its administration to patients with specific traumatic injuries (AACE, 2019).

Trauma patients frequently experience severe pain levels (McKay, 2013); analgesia on the ladder's first step is therefore ineffective in these patients. This lack of or inadequate pain management, accompanied by the gap in analgesia provision for prehospital trauma patients, highlights the importance of introducing alternative analgesia.

Ketamine is a dissociative agent, attaining pain amnesia and analgesia by creating a trance state (Sih et al, 2011). For years, ketamine has been used safely and effectively as an analgesic in international civilian and military settings (Buckland et al, 2018). It is used for both sedation and analgesia in Australian medical retrieval services (Hollis et al, 2016). Ketamine was first used in the UK as an in-hospital anaesthetic agent (Gales and Maxwell, 2020), then later employed as a postoperative analgesia (Radvansky et al, 2015).

Ketamine has now been introduced into the prehospital environment in the UK. It has been used by London Helicopter Emergency Medical Service (HEMS) for sedation since it was established, and later as an analgesic (Bredmose et al, 2009). A review of the administration of ketamine as an analgesic and sedative by critical care paramedics (CCPs) within HEMS demonstrated that, following the first year of training on ketamine administration, all CCPs safely administered it with no adverse effects (McQueen et al, 2014). Successful analgesic use by advanced paramedic practitioners has also been demonstrated, with 94% of recipients experiencing pain reduction after administration with no adverse effects (Edwards et al, 2016).

However, both studies highlight concerns relating to the need for additional education and recommended level of exposure to ensure competence in this skill is maintained. Nevertheless, an audit review of ketamine administration by hazardous area response team (HART) paramedics showed that those who received two days of classroom training and examinations on the relevant patient group directive were able to administer ketamine safely as an effective analgesia (Metcalf, 2018). This evidence suggests that paramedics are capable of IV ketamine administration at an analgesic dose.

The feasibility of this training for paramedics who have no additional education, experience or qualifications, paired with its efficacy for traumatic pain in multiple clinical environments, demonstrates there is a clear scope for including ketamine in ambulance service paramedic analgesic drugs.

Therefore, the author conducted a systematic literature review to establish whether introducing IV ketamine to non-specialist UK paramedics could improve pain management of prehospital trauma patients and whether its use is safe for this purpose.

For the purpose of this review, the terms ‘paramedic’ or ‘non-specialist paramedic’ refer to the general paramedic—a paramedic who has the basic legal level of training to be qualified as a paramedic, works in a frontline ambulance service and does not have any/is not registered as having further specialist experience, education or qualifications such as CCP, HART paramedic, advanced paramedic practitioner, specialist paramedic and so forth.

Methods

The author independently chose to conduct a systematic literature review as it allows simultaneous searches of electronic databases while being the most effective method to find the best current, relevant literature (Hewitt-Taylor, 2017). The review was based on the following questions:

Before carrying out the search, the author developed inclusion and exclusion criteria to focus it (Table 2).

| Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Population | Intervention | Outcome | Time |

| 1 | Trauma patient* | Ketamine | Pain management | Pre-hospital* |

| 2 | Traumatic injur* | Subdissociative ketamine | Pain* | Prehospital |

| 3 | Trauma | Low-dose ketamine | Pain relie* | Ambulance |

| 4 | Injur* | LDK | Analgesi* | Paramedic* |

| 5 | Bone fracture | Intravenous ketamine | Administration | Out-of-hospital |

| 6 | Introduction | Emergency medical service | ||

| 7 | Infusion | Emergency | ||

| 8 | Effect* | |||

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Adult (18+ years) | Children (<18 years) |

| Traumatic pain | Acute (non-traumatic) or chronic pain |

| Emergency medicine (prehospital environment, or emergency department/setting | Military setting or non-emergency e.g. general practice |

| English language | Non-English language |

| Published 2009–2021 | Published before 2009 |

| Primary research | Secondary research |

| Quantitative research | Qualitative research |

| Intravenous ketamine | Ketamine administered by a non-intravenous route e.g. intramuscularly |

| Ketamine as an analgesic | Ketamine as a sedative, anaesthetic, etc |

| Corresponds with question/aims | Full text not available |

The first stage of the review included an extensive search of the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL), Medline and the Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED) database. The search was performed using keywords relevant to the study aims (Table 1). Boolean logic operators were used, combining and linking separate search terms, ‘OR’ was used between all variables of search groups to refine and focus results; ‘AND’ was used to join search groups (Coughlan et al, 2013). The University of the West of England library and Google Scholar were used to gain access to full articles. Furthermore, a snowballing technique was used to gather additional relevant studies. Contact was attempted with the authors of the KETAMORPH study, a trial currently being undertaken, but no response was received.

Military paramedics receive different and more specialised training compared to non-specialist UK paramedics, and perform their treatment in a different environment with equipment that differs from that used by UK paramedics. The Ministry of Defence (2021) demonstrated that military and civilian staff stationed overseas for military operations were injured most commonly by explosive devices and small firearms.

An analysis of Trauma Audit Research Network statistics for major trauma demonstrated that the largest cause of trauma in 2019 was car-related road traffic collisions (Rajput et al, 2021), and in 2015 was falls from a low height (Kehoe et al, 2015).

As the two populations have different injury causes and hence inconsistent injury patterns, military data are not generalisable to the UK prehospital population. Additionally, military medics receive different training to UK paramedics. Military paramedics and research were thus excluded.

Additionally, the author excluded intramuscular and intranasal ketamine, and explored only IV ketamine. This was because the author was a novice researcher and felt that, owing to the large volume of evidence that would be produced if all routes of ketamine administration were included, exploring one route of administration and having a more focused subject would allow her to best answer the research question and meet the study aims. The IV route was chosen based on the larger existing evidence base on the success of this route in hospital, military and specialist clinician settings as evidenced above.

Results

Categorising the content

The following two themes were derived from the eligible articles:

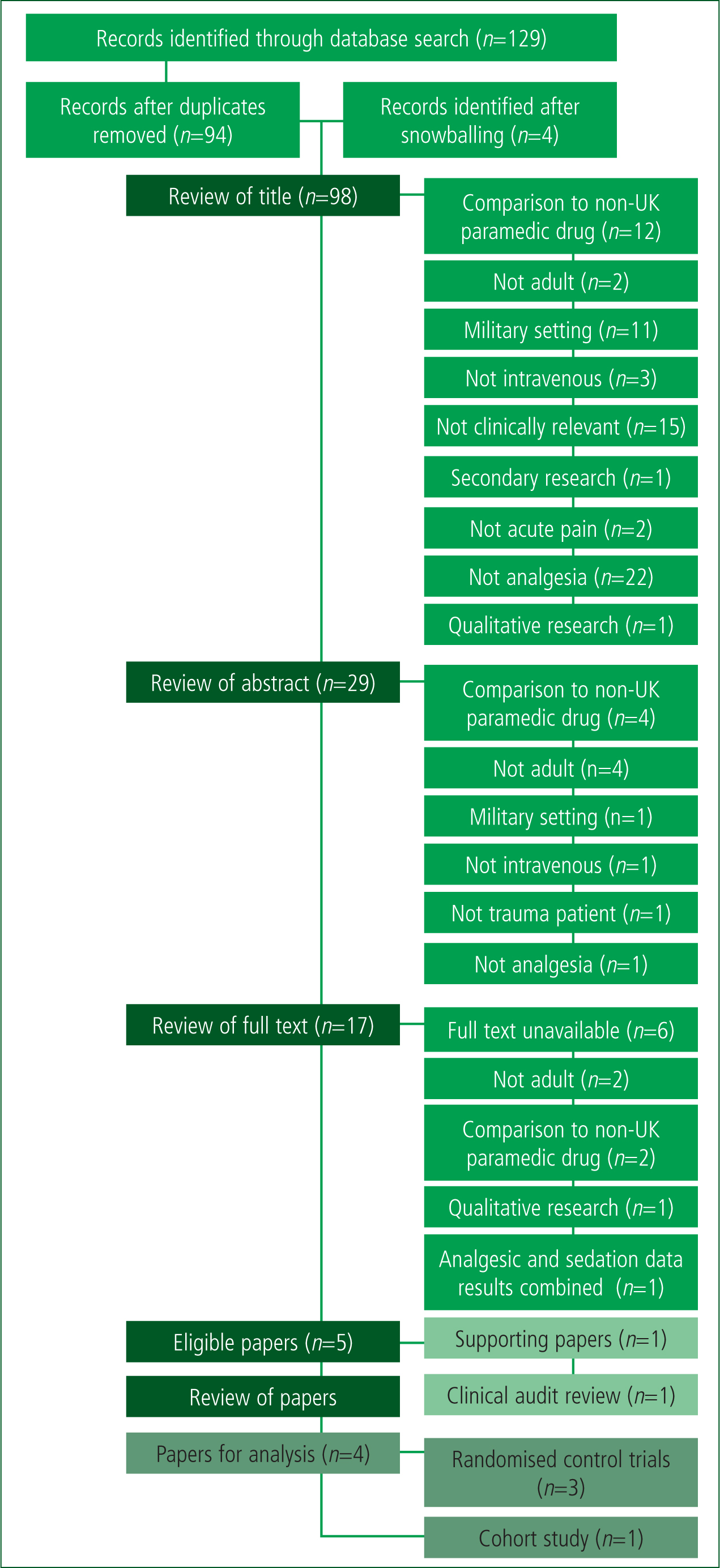

The initial search produced 129 results, and four studies were found through snowballing. Of the 98 non-duplicate records reviewed by title, 29 were deemed potentially eligible and had their abstracts reviewed. The author performed analysis on 17 full texts and deemed five papers suitable to the research aim as per the PRISMA diagram (Figure 1) (Page et al, 2021).

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklists were used to determine study quality; these were chosen as they are widely valued tools and their use within systematic reviews demonstrates good practice (Aveyard, 2019).

Of the full texts, only four (three randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and one cohort study) were deemed appropriate. The clinical audit review by Metcalf (2018) was not among the final studies, although it was among those eligible. As it played a large role in the reasoning and justification for the review, the author chose to not include it in the final studies but to use it as supporting evidence.

Therapeutic effectiveness of ketamine

The multicentred RCT by Wiel et al (2015), conducted in France, compared the therapeutic effect, adverse event occurrence and vital sign changes of continuously infused IV ketamine versus IV saline, administered in prehospital orthopaedic injuries secondary to trauma, in patients requiring analgesia and transport to the ED. Majidinejad et al, (2014) undertook a multicentred, double-blinded RCT to identify the superiority of ketamine versus morphine when administered to long-bone fracture patients in the ED in Iran. Jennings et al (2012) conducted a multicentred, open-label RCT in Australia, exploring changes in pain intensity and incidence of adverse effects and effects on vital signs of morphine compared to morphine and ketamine combined. Johansson et al (2009) performed a randomised prospective cohort study in Sweden, comparing pain scores, adverse effects and vital signs between morphine versus a combined ketamine and morphine dose administered by prehospital nurses. These studies are summarised in Table 3.

| Author | Country | Sample size | Drug administration/dose and pain measurement tool | Pain scores | Adverse effects and vital signs observed | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wiel et al (2015) | France | 66 | Initial bolus of intravenous (IV) morphine 0.1 mg/kg administered to all participants |

VAS scores with standard deviation at initial and final time respectively: ketamine=8.5±1.5 and 3.1±2.3; saline=8.1±1.3 and 3.7±2.7 |

Vital signs: Blood pressure, heart rate, pulse oximetry and nasal ETCO2 showed no significant difference between groups. There was a difference between Ramsay scores, with one patient in the ketamine group experiencing excessive sedation. |

0.5 |

| Majidinejad et al (2014) | Iran | 123 | Initial doses: ketamine: 0.5 mg/kg; and morphine 0.1 mg/kg. |

NRS score change (reduction) with standard deviation: ketamine=2.7±1.8; and morphine=2.4±1.5 |

Adverse events: No complications in the morphine group |

<0.001 |

| Jennings et al (2012) | Australia | 135 | Initial 5 mg loading dose of morphine in both groups. |

NRS change from initial to final time: Ketamine=−5.6 (95% CI −6.2 to −5.0) |

Vital signs: Monitored at 10-minute intervals. Pulse rate, respiratory rate, systolic blood pressure (SBP), and Glasgow Coma Scale were monitored. Slight increase in mean SBP in ketamine group compared to decrease in morphine group. No clinically significant changes. |

No P value |

| Johansson et al (2009) | Sweden | 27 | All received a morphine loading dose of 0.1 mg/kg. |

Initial NRS scores for the ketamine and morphine groups were similar NRS scores at scene and admission respectively were: ketamine 7.5±1.8 and 3.1±1.4; and morphine 8.5±1.6 and 5.4±1.9. |

Vital signs: SBP changes observed at start and final time: ketamine arm 142±33 mmHg and 167±32 mmHg; morphine arm 143±17 mmHg and 134±21 mmHg. Significant difference between groups. No significant difference found for heart rate, respiratory rate or SPO2 |

<0.05 |

All of the studies reported pain assessment before and following ketamine administration. Three studies explored the therapeutic efficacy of ketamine combined with morphine, with two of these comparing the combined drugs to morphine alone, and one to saline (Johansson et al, 2009; Jennings et al, 2012; Wiel et al, 2015). Majidinejad et al (2014) evaluated the administration of ketamine alone compared to morphine.

Each study demonstrated a significant reduction in pain scores in the ketamine group. When ketamine or morphine were administered after a loading dose of morphine, two studies demonstrated a significant superiority of speed and intensity of pain reduction in the ketamine group (Johansson et al, 2009; Jennings et al, 2012). One study demonstrated no significant difference in pain score reduction between groups, but found that ketamine combined with morphine reduced pain in line with morphine alone (Wiel et al, 2015). Additionally, one study demonstrated a significant pain reduction, in line with morphine, when ketamine was administered independently (Majidinejad et al, 2014). Overall, this suggests that ketamine, whether alone or in combination with morphine, is effective at reducing traumatic pain.

Safety of IV ketamine administration by paramedics

All of the studies reported ketamine had adverse effects. One study explored adverse effects in a group who were administered ketamine alone (Majidinejad et al, 2014). The other studies explored adverse effects with ketamine and morphine combined; these three studies also explored vital signs (Johansson et al, 2009; Jennings et al, 2012; Wiel et al, 2015).

All of the studies concluded that adverse effects were higher in ketamine-and-morphine-combined groups and ketamine-alone groups compared to those receiving saline/morphine alone. However, only one study concluded there was a significant difference between groups for adverse effects but added that, overall, they were uncommon and not life threatening (Jennings et al, 2012). Wiel et al (2015) and Johansson et al (2009) found a non-significant difference between groups, while Majidinejad et al (2014) failed to state whether adverse effects were significantly different between groups.

One study found no significant differences in vital signs between the morphine and ketamine groups (Jennings et al, 2012). Two studies demonstrated a significant difference in vital signs between groups; Wiel et al (2015) found a difference in Ramsay scores, while Johansson et al (2009) concluded a significant increase in systolic blood pressure (SBP) in the ketamine group. Jennings et al (2012) also observed an increase in SBP in the ketamine group but, when compared to the morphine group, this was found to be non-significant.

Overall, the studies came to a variety of conclusions. In general, they suggest ketamine has more adverse effects than morphine, but all adverse effects exhibited are minor and do not mean it is not safe to administer ketamine.

The data show ketamine causes a rise in SBP. Nevertheless, co-treatment with morphine and ketamine has no greater complications than when ketamine is administered alone.

Discussion

The aim of this review was to identify whether IV ketamine could be used by non-specialist UK paramedics as an additional form of analgesia to successfully and safely relieve pain in prehospital adult trauma patients, who are currently poorly managed. Existing systematic reviews surrounding the use of ketamine focus on military settings, ED patients, generalised acute pain or combined adult and child populations.

Therapeutic effectiveness of ketamine

The main findings of this review demonstrated that, when administered by itself, ketamine relieves pain in line with morphine. This conclusion has also been reflected in similar, previous systematic reviews. A 2019 systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that ketamine relieves traumatic pain at a similar level to opioid analgesics while having fewer side effects (Yousefifard et al, 2019).

Nevertheless, the data presented in the meta-analysis combines adult and paediatric participants, which presents a significant weakness as pharmacokinetic processes differ significantly between paediatric and adult populations, and result in different adverse drug reactions (Fernandez et al, 2011; Blake et al, 2014). Hence, it is important to have data exploring efficacy and side effects separately for the two age groups. Additionally, the study explores respiratory complications and haemodynamic instability as side effects but does not present or discuss any data on the vital signs of the participants.

Jennings et al (2011b) performed a prehospital based meta-analysis, focused predominantly on traumatic pain, with all studies apart from one including participants who were experiencing trauma-induced pain. They concluded that IV ketamine has equal efficacy to opioids.

Furthermore, a systematic review by Wongtongkam and Adams (2020) demonstrated successful pain reduction from ketamine. However, the review did not focus solely on ketamine's analgesic potential but also examined its triple therapeutic effectiveness. Furthermore, children are included in the exclusion criteria but one of the studies considered used participants aged from 17 years old, and the mean age of the included case series was 16 years old. Additionally, they include a study by Tran et al (2014) who used 24 participants under the age of 15 years old and did not present separate data for pain scores or side effects for adult and child participants, potentially skewing the results of the review. Finally, they compared ketamine to drugs that are not used by non-specialist paramedics in the UK. Therefore, there are weaknesses in this review, plus its aims differ from this author's.

Therefore, while these systematic reviews support the results of this study, the quality of the reviews could be better and they have limited generalisability to the current review.

The results further demonstrated a trend showing that co-administration of morphine and ketamine results in a greater reduction of pain than morphine alone. The aforementioned review by Yousefifard et al (2019) further demonstrated that ‘to some extent’ ketamine and morphine combined provides superior pain relief than morphine alone. Furthermore, the co-administration of ketamine and morphine has been shown to be effective at reducing procedural wound-care pain compared to morphine alone (Arroya-Novoa et al, 2011).

Overall, the analysis of the studies highlighted both strengths and weaknesses. The use of RCTs allowed causal relationships to be identified, and those that used blinding avoided performance bias. Furthermore, adequately powered results plus narrow confidence intervals allowed statistical significance to be detected. These characteristics imparted high internal validity; however, where these were not achieved, internal validity was reduced. Nevertheless, overall high internal validity and reliability of the conclusions drawn were demonstrated by the studies.

Unfortunately, significant concerns remain regarding the generalisability of the results to the research question. When reviewing this in relation to pain reduction, the studies explored only patients with long bone fractures and orthopaedic injuries, reducing generalisability to pain from all traumatic injuries. This reduced external validity. With morphine being deemed less effective in isolated limb injuries than against other cause of traumatic pain (Sharma and Mehta, 2014), and the exploration of ketamine within these studies strongly looking at this injury subgroup, the true analgesic potential of ketamine may not have been demonstrated. However, the clinical audit review evidenced in the justification for the review being carried out demonstrated 100% pain reduction when HART paramedics administered ketamine alone to patients experiencing a range of traumatic injuries (Metcalf, 2018).

However, with these studies indicating ketamine has analgesic properties equal to morphine in these subgroups, and lower limb injuries being the greatest indication for ketamine administration prehospitally (Cowley et al, 2018), there could be little benefit from ketamine introduction. Nevertheless, further research is required to determine whether ketamine may be a superior analgesia in other causes of traumatic pain.

Safety of IV ketamine administration by paramedics

Whether combined or independent, ketamine can be administered safely by paramedics. It has more adverse effects than morphine alone, but these are minor in nature. These findings are supported by a UK prehospital retrospective trauma database analysis review, which found no significant complications associated with the administration of IV ketamine by HEMS clinicians in prehospital trauma patients (Bredmose et al, 2009). Buckland et al (2018) further supports that the administration of prehospital ketamine is safe, with 94% of paramedics comfortable administering IV ketamine, 95% stating they would use the drug again in similar circumstances and 14% witnessing non-fatal adverse effects. Additionally, McKay (2013) concluded ketamine administration is safe with non-significant adverse effects and vital sign changes when compared to morphine.

As none of the studies explored were conducted within the UK, one was set in the ED, not the prehospital environment, and one involved prehospital nurses not paramedics, generalisability of the results to the population being explored within the research question is reduced. Nonetheless, the conclusion paired with the UK study by Bredmose et al (2009) allows concern regarding generalisability of the results to be reduced.

This is supported by Cowley et al (2018) who demonstrated that only 4% of patients experienced adverse effects and that the administration of ketamine within the prehospital environment was safe. Furthermore, the meta-analysis by Jennings et al (2011b), which included a sample with varying traumatic injuries and causes of traumatic pain, also concluded that IV ketamine was safe to administer in the prehospital environment.

Further concerns about generalisability arise because trauma patients with potential head injuries were included. Although all adverse effects were minor in nature and ketamine was demonstrated to be safe in trauma patients, hypertension was demonstrated in patients with traumatic injuries, hence those with head injuries are contraindicated for inclusion in the study (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2015a). However, Svenson and Abernathy (2007) highlighted hypertension has benefits in patients with traumatic brain injury, suggesting hypertension prevents harmful hypotension, demonstrating that ketamine has neuroprotective properties in these patients. The exclusion of participants with head injuries and conflicting evidence create concern over whether ketamine can be administered safely to patients with head injuries.

Additionally, the increased SBP in the ketamine groups requires further exploration. The hypertensive properties could be seen to be potentially beneficial as they avoid the hypotension that can follow morphine administration. However, hypertension in haemorrhagic patients could be harmful owing to the potential for clot disruption (Wiles, 2013), indicating the need for avoidance of ketamine in these patients—something that goes unexplored within the studies.

Implications for practice

Currently, the first-line analgesic for major trauma patients is IV morphine (NICE, 2015b). The author found consistency in the conclusions produced, with studies demonstrating that ketamine alone does not provide superior pain relief but relief in line with morphine. Co-administration of ketamine and morphine provides superior pain relief to morphine alone. This suggests it could be used by non-specialist paramedics to relieve traumatic pain to at least the same level as morphine.

The review evidenced ketamine causes minimal adverse effects with an increase in SBP, suggesting IV ketamine can be safely administered, avoiding hypotension and respiratory complications associated with morphine, supporting its introduction as an additional analgesia for patients who receive inadequate pain relief.

Although it has been demonstrated that ketamine can provide pain reduction in line with morphine, the true properties of ketamine in relation to traumatic pain and its adverse effects cannot be determined as it was explored in combination with morphine and in limited injury groups.

The author suggests that a conclusion on whether IV ketamine should be introduced to non-specialist UK paramedics as an analgesia in prehospital adult trauma patients cannot be drawn without further evidence on ketamine for people with head injuries, in its use in the UK prehospital environment and on its hypertensive properties.

Additionally, faults in study design and generalisation can be resolved only by future research.

Therefore, the author recommends a rigorous, large scale, UK, prehospital non-specialist paramedic-based, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, with adequately powered secondary outcomes, exploring ketamine administration in all trauma patients, including those with haemorrhage and head injuries. This would ensure a patient-focused outcome is achieved and explored in relation to all causes of traumatic pain and safe prehospital administration.

Until this is undertaken, the author suggests that current guidance by NICE (2015b) is followed, and morphine is administered to trauma patients or other analgesia where morphine is contraindicated.

Limitations

A key limitation is that the author is a novice researcher so the literature review may not have been conducted to the standards of an experienced research team (Gerrish and Lathlean, 2015). The inexperience of the author potentially subjected the review to methodological errors and bias (Aveyard, 2019) while preventing the author from performing a thorough meta-analysis of pooled data.

Additionally, reliability concerns present through selection bias, owing to time constraints preventing the author from assessing all papers individually (Bowling, 2005). This prevented a review including intranasal and intramuscular ketamine owing to the scale of evidence relating to this, which limited the review to the exploration of the IV route only.

Due to financial constraints, the author accessed literature only via the university library, Google Scholar and in the English language. These factors acted as large confounding variables (Conn et al, 2003; Aveyard, 2019).

Additionally, the studies used samples exploring limited injury groups, while excluding head injuries and failing to explore the effect of ketamine's hypertensive properties on haemorrhagic patients. Furthermore, the lack of research involving prehospital non-specialist paramedics and within the UK reduces the quality of conclusions drawn.

Conclusion

This review highlights the clear analgesic effectiveness of IV ketamine in adult trauma patients; however, it also demonstrates evidential gaps in safety of administration. Additionally, there was limited generalisation of results to non-specialist paramedic practice.

Therefore, the results of the review are insufficient to prompt change to paramedic-practice. The author's recommendations for further research should be acted on to help close gaps in evidence and increase external validity regarding UK non-specialist paramedic practice.