Sepsis has become a common condition. In a review of cases in England, Wales and Northern Ireland the treated incidence of severe sepsis in intensive care units per 100 000 population rose from 46 in 1996 to 66 in 2003, with the associated number of hospital deaths per 100 000 population rising from 23 to 30 (Harrison et al, 2006).

In an attempt to tackle this rise, the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) was launched in 2002 and updated successively with a primary focus on achieving a 25% reduction in the mortality of severe sepsis (Dellinger et al, 2004; Robson et al, 2009; Dellinger et al, 2013).

In-hospital early goal directed therapy (EGDT) has been evaluated in three multicentre studies (ARISE Investigators et al, 2014; ProCESS Investigators et al, 2014; Mouncey et, 2015), it has been demonstrated that there is no benefit of EGDT in comparison to usual care. It is important to note that though EGDT has shown to have no benefit, standard care has evolved where patients receive early recognition, fluid and antibiotic treatment routinely.

In 2007, Survive Sepsis supplemented the SSC (Robson and Daniels, 2008) aiming to improve the knowledge of sepsis to ward nurses and junior doctors. The ‘Sepsis Six’ evolved deriving basic tasks from a resuscitation bundle that were easily achievable with a view to improve the immediate care (Daniels, 2011).

Due to the pressure on emergency departments to complete all the components of the Sepsis Six within 1 hour, research has suggested that pre-hospital clinicians may have the opportunity to intervene at an earlier stage (Robson et al, 2009; Báez et al, 2010; Cronshaw et al, 2011; Daniels, 2011). If septic shock is left untreated it can increase mortality by 8% per hour (Kumar et al, 2006).

In the US, Studnek et al (2012) used prospective data to investigate associations between emergency medical services (EMS) and emergency department (ED) care of patients treated with EGDT. In this study, patients transported by EMS had a shorter time from ED triage to initiation of EGDT as those not transported by EMS, and when sepsis was documented there was also a significant decrease in time to antibiotics. This supports other research (Robson et al, 2009; Báez et al, 2010; Cronshaw et al, 2011) in suggesting that improved awareness in pre-hospital clinicians could have a direct impact upon subsequent care of sepsis patients (Studnek et al, 2012).

The UK Sepsis Group Pre-hospital Sepsis Committee has made recommendations to the Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee for the latest edition of its guidelines (Association of Ambulance Chief Executives, 2013; UK Sepsis Group, 2013).

Robson et al (2009) state the use of a pre-hospital screening tool may significantly improve outcomes. The UK Sepsis Group (2013) state that currently there is no tool validated for pre-hospital use and ambulance services should develop local procedures for septic patients.

Within the area being investigated for this study, an introduction to sepsis to all frontline staff has been circulated by a 1-hour teaching session done on an annual statutory and mandatory training day. The training included brief information about the condition and introduction to a screening tool. Staff were also issued with a ‘patient care update’ regarding sepsis on 6 July 2013. Effectiveness of the training and attitudes towards the implementation of such a screening tool in this setting are currently unknown.

In the surviving sepsis campaign Dellinger et al (2004) comment that:

‘Similar to an acute myocardial ischaemic attack and an acute brain attack, the speed and appropriateness of therapy administered in the initial hours after the syndrome develops are likely to influence outcome.’

Recently the SSC guidelines have indicated the importance of education and process change in the acute care setting to tackle the sepsis burden (Dellinger et al, 2013).

In a survey conducted among physicians, 87% felt that the symptoms of sepsis can easily be attributed to other conditions, creating problems of late or misdiagnosis (Poeze et al, 2004). Despite this, sepsis recognition and management is not currently explored in depth on the curriculums training paramedics.

If sepsis bundles are to be used in the pre-hospital environment the knowledge of the clinicians needs to be assessed to identify suitable approach to new guidelines and possible training needs:

‘To reliably identify severe sepsis demands a degree of awareness, vigilance and knowledge among individual healthcare workers and within the organisation itself’

In the US, the Pre-hospital Sepsis Project observed out-of-hospital emergency medical services' knowledge through clinical scenarios and concluded that their cohort had ‘poor understanding of the principles of diagnosis and management of sepsis’ (Báez et al, 2010).

In the UK to date no research has studied the knowledge of pre-hospital staff in the field of sepsis. This study has been undertaken to understand the knowledge and awareness of the UK population and identify any training needs.

It is also important to inform the introduction of a screening tool so it is used effectively. Attitudes towards the implementation of such a screening tool in this setting are currently unknown. Knowing the pre-hospital clinician perspective on this topic will allow for a screening tool to be implemented in the best way possible so that it will be used alongside clinical acumen.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study of qualified emergency workers in the North East. The study has no legal or policy requirements for review by a research ethics committee. The research is limited to involvement of staff as participants by nature of their professional role. The study has undergone NHS Trust permission.

A survey was prepared by reviewing the literature, identifying gaps regarding the current statuses of the knowledge and experience of the pre-hospital cohort. An expert in the sepsis field, academic tutors and North East Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust (NEAS) clinical and research and development departments assisted with the content of the survey and case studies. A group of pre-hospital clinicians piloted the survey before distribution to assess readability and length of time taken to complete.

A 19-item survey was distributed to employees of NEAS via email. The email included a participation information sheet and a link to the survey. Informed consent was assumed on return of the survey. A follow up email was sent from the research department to remind staff about the survey at 2 and 6 weeks after first contact.

Access to computers or time to complete the survey electronically were realised to be insufficient during the data collection period. Therefore the survey was distributed as a hard copy and sent to staff at their respective ambulance stations with a return envelope to maximise the opportunity for staff to participate. Participation was voluntary and all responses were anonymous.

All qualified paramedics (n=529, 80.2%) and advanced technicians (n=131, 19.8%) employed by NEAS were invited to participate in the study. Emergency care support workers and student paramedics were excluded from the study as these staff members have no diagnostic responsibility for patients.

Data were collected showing baseline information on employment and training. Further questions investigated knowledge and awareness of sepsis, screening tools and opinions of staff around the screening tool. The survey included four case studies. The case studies were used to evaluate the current management of patients that have history of infections and/or clinical indicators of sepsis.

Analysis

The data collected via the electronic survey formed an excel file which were then manually inputted into IBM Corporation SPSS Statistics version 19.0.0.1 for analysis. Returned hard copies of the survey were added manually into the statistics package.

All items in the survey were nominal or ordinal (categorical) data. Numerical codes were allocated to the data. Missing data were coded separately.

Data were summarised using the mode to observe the most frequent value in the results. Frequency distributions were viewed to identify trends in the data. Due to the small sample size Minitab 16.0 was used to calculate the binominal distribution to obtain exact 95% confidence intervals. Chi-square tests were used to identify associations in the data. Associations were assumed if the p value was less than 0.05.

Results

Six hundred and sixty clinicians had the opportunity to complete the survey either electronically or manually during the period of 20 November 2012 to 2 March 2013 (4 months). A total of 144 clinicians completed the survey generating a 21.8% response rate. There were some missing data, therefore numbers of respondents per question are quoted within the results. Table 1 shows demographic descriptors of the sample.

| Population sample | Study sample | |

|---|---|---|

| Level of qualification, (%) n | n=660 | n=143 |

| Advanced technician | (19.8) 131 | (4.2) 6 |

| Paramedic | (80.2) 529 | (95) 137 |

| No response | (0.7) 1 | |

| Qualification for the role, (%) n | n=142 | |

| IHCD technician | 6 | |

| IHCD paramedic | 50 | |

| FdSc paramedic science | 74 | |

| BSc paramedic science | 12 | |

| No response | 2 | |

| Length of time in service, (%) n | n=142 | |

| 0–5 years | 26 | |

| 6–10 years | 39 | |

| 11–15 years | 26 | |

| 16–20 years | 14 | |

| Above 20 years | 37 | |

| No response | 2 |

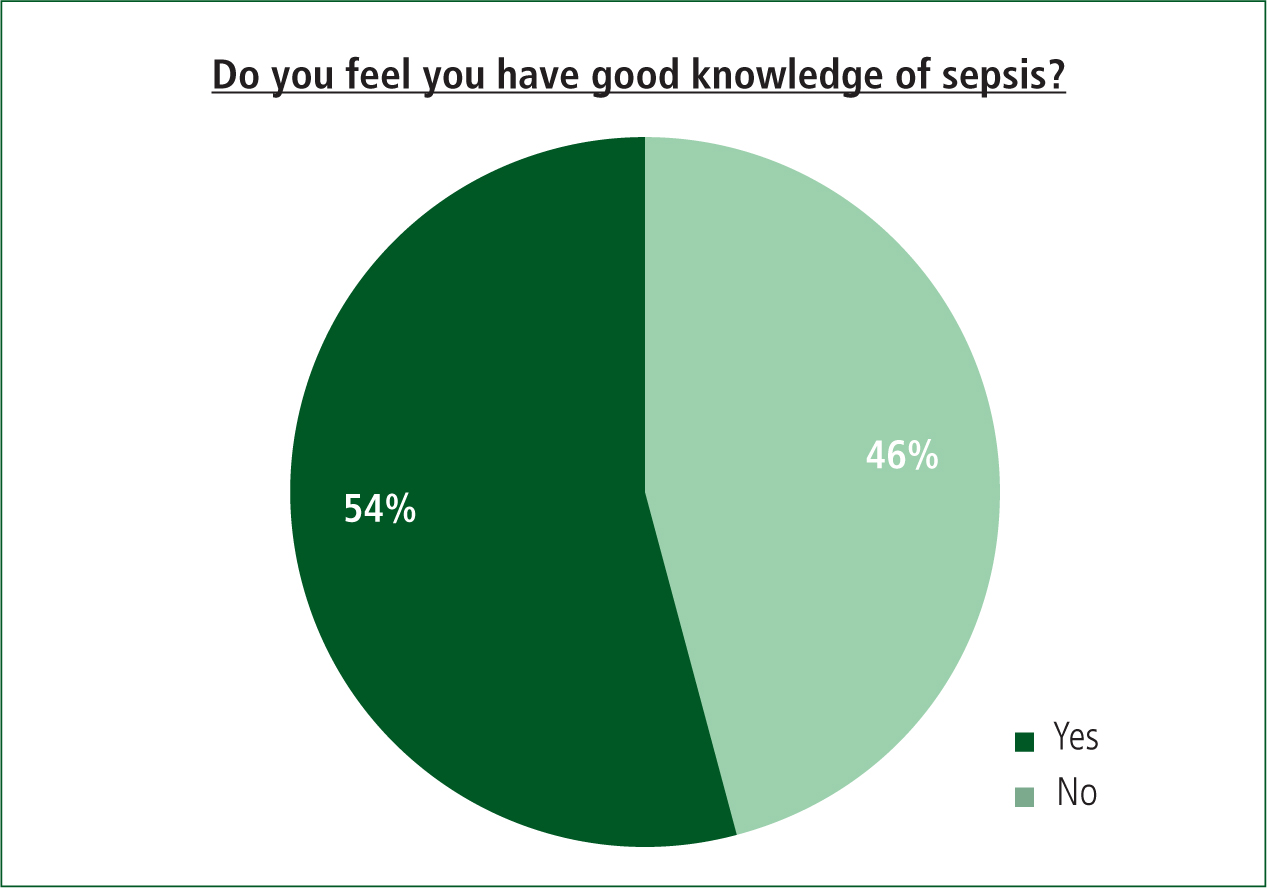

When clinicians were asked if they felt that they had good knowledge of sepsis, 54% (n=76, CI 46%, 62%) stated yes, with 46% (n=65, CI 38%, 54%) stating they did not feel like they had good knowledge (Figure 1).

Using chi-square analysis to test for associations, there was no significant difference (p=<0.05) between the respondents' knowledge and education level (p=0.678), or knowledge and number of years in service (p=0.999).

Although almost half of the respondents thought they had poor knowledge of sepsis, 46% (n=100, CI 38%, 54%) indicated they were aware of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign and 85.2% (n=121, CI 79%, 91%) had seen or heard of a Sepsis Screening Tool.

53% (n=75, CI 44%, 60%) of respondents suggested that they thought emergency departments should treat sepsis immediately, with 41% (n=58, CI 32%, 49%) stating they should be treated within the hour and 4% within 2–4 hours and 1% within 4 hours, respectively.

Training

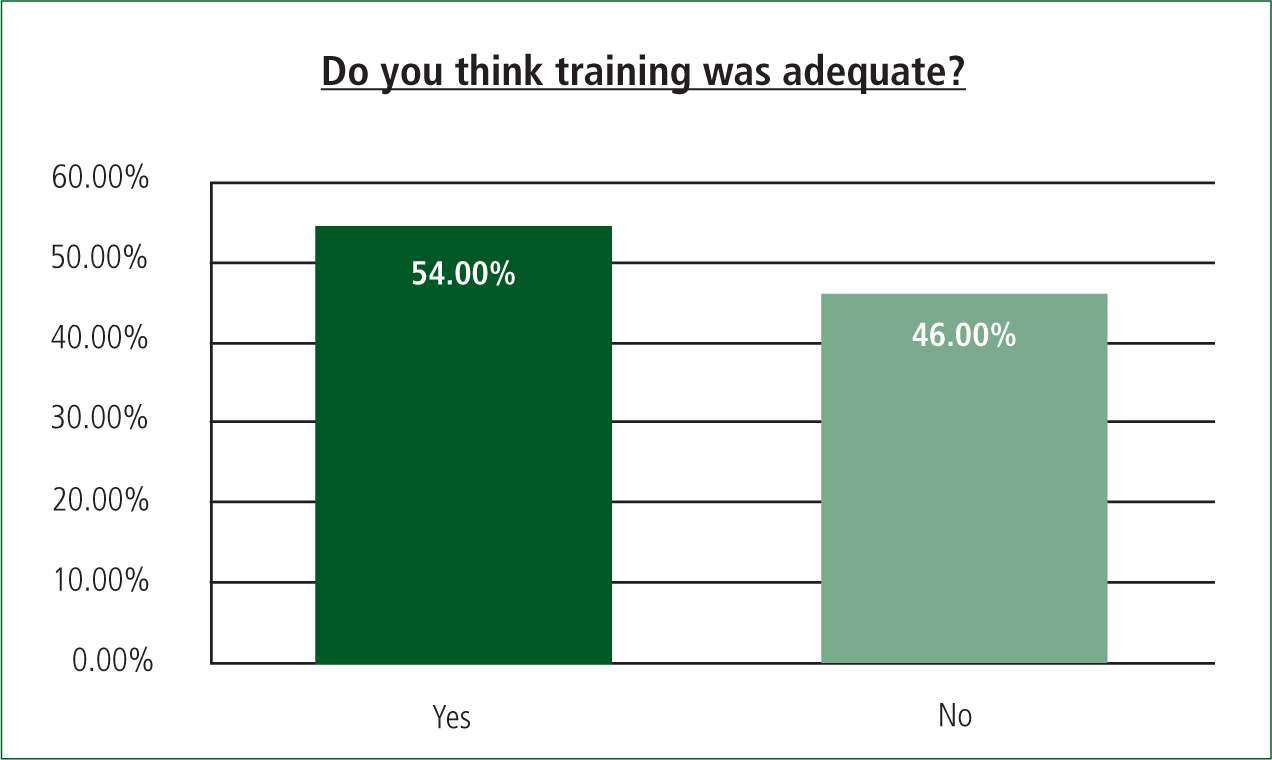

At the time the survey was distributed, 70.8% (n=102, CI 63%, 79%) of respondents had undergone employer training in sepsis. 46% (n=103, CI 36%, 56%) stated they did not think it was adequate (Figure 2) and 98% (n=140, CI 94%, 99%) of all respondents stated they would like to receive further training on sepsis.

These results seem to show a trend away from the training fulfilling clinicians' needs. However, Tables 2 and 3 below demonstrate chi square tests showing significant associations between employer training and clinicians' view of their knowledge (p=0.05) and knowledge level and awareness of Surviving Sepsis Campaign (p=0.01).

| Previous employer training | |||

| Yes | No | ||

| Count | Count | ||

| Good knowledge of sepsis? | Yes | 61 | 15 |

| No | 39 | 26 | |

| Chi-square | 6.976 | ||

| df | 1 | ||

| Sig. | 0.08 | ||

| Do you feel you have good knowledge of sepsis? | |||

| Yes | No | ||

| Count | Count | ||

| Aware of Surviving Sepsis Campaign? | Yes | 61 | 36 |

| No | 14 | 29 | |

| Chi-square | 11.018 | ||

| df | 1 | ||

| Sig. | 0.01 | ||

With regard to further training, results showed 44% (n=140, CI=35%, 52%) thought a study day on sepsis would be the best delivery. Other methods for further training chosen were e-learning (19%), mandatory update (19%), and written material (13%).

Screening tool

97% (n=138, CI 92%, 99%) of clinicians thought a screening tool would help identify patients in the pre-hospital setting. Table 4 demonstrates clinicians would also use the tool while assessing patients.

| Would you use the tool? | |||

| Yes | No | ||

| Count | Count | ||

| Screening tool alongside clinical acumen? | Yes | 127 | 0 |

| No | 2 | 2 | |

| 1 | 0 | ||

| Chi-square | 64.985 | ||

| df | 2 | ||

| Sig. | .000 | ||

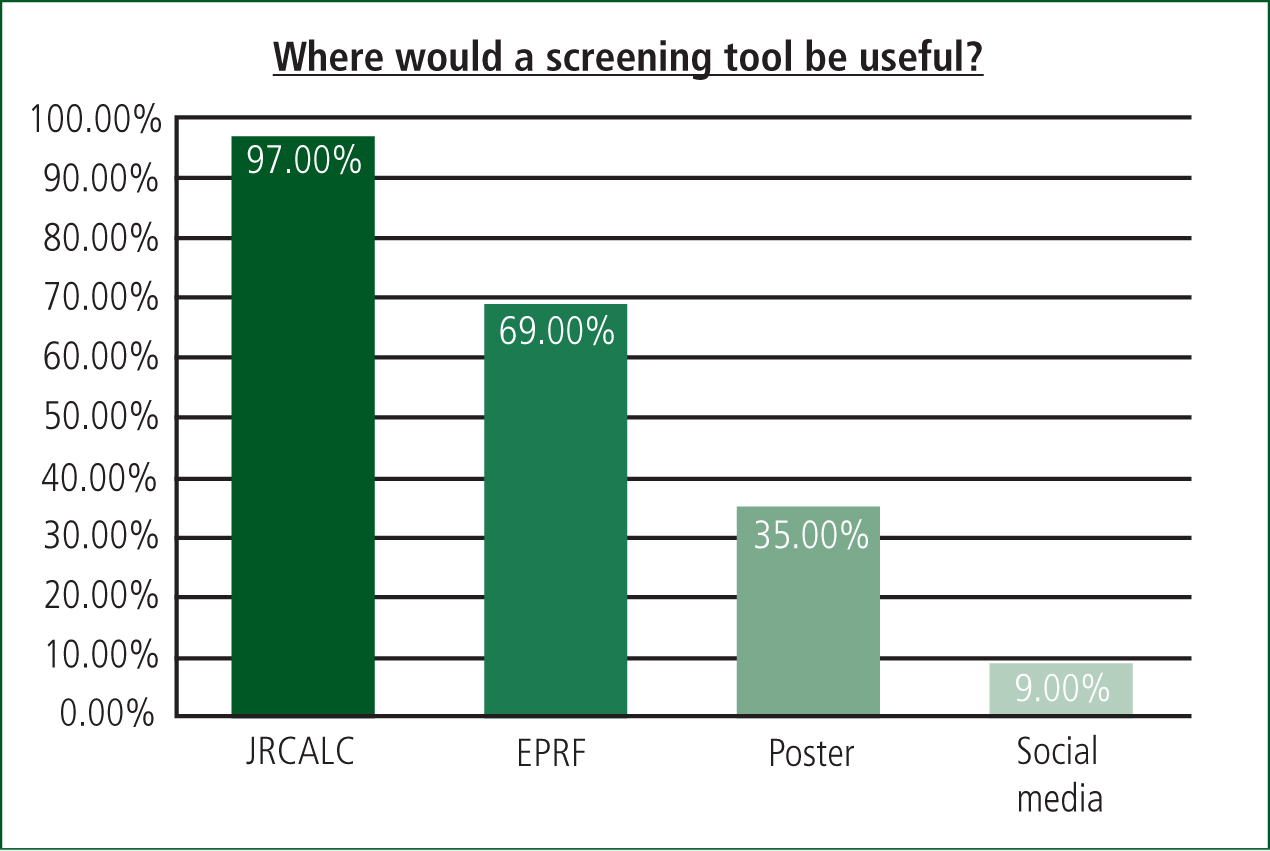

To identify where the screening tool would be most useful to clinicians a multi-response analysis was performed on the data. Figure 3 demonstrates where clinicians stated a screening tool would be best placed in the ambulance for ease of use.

Case studies

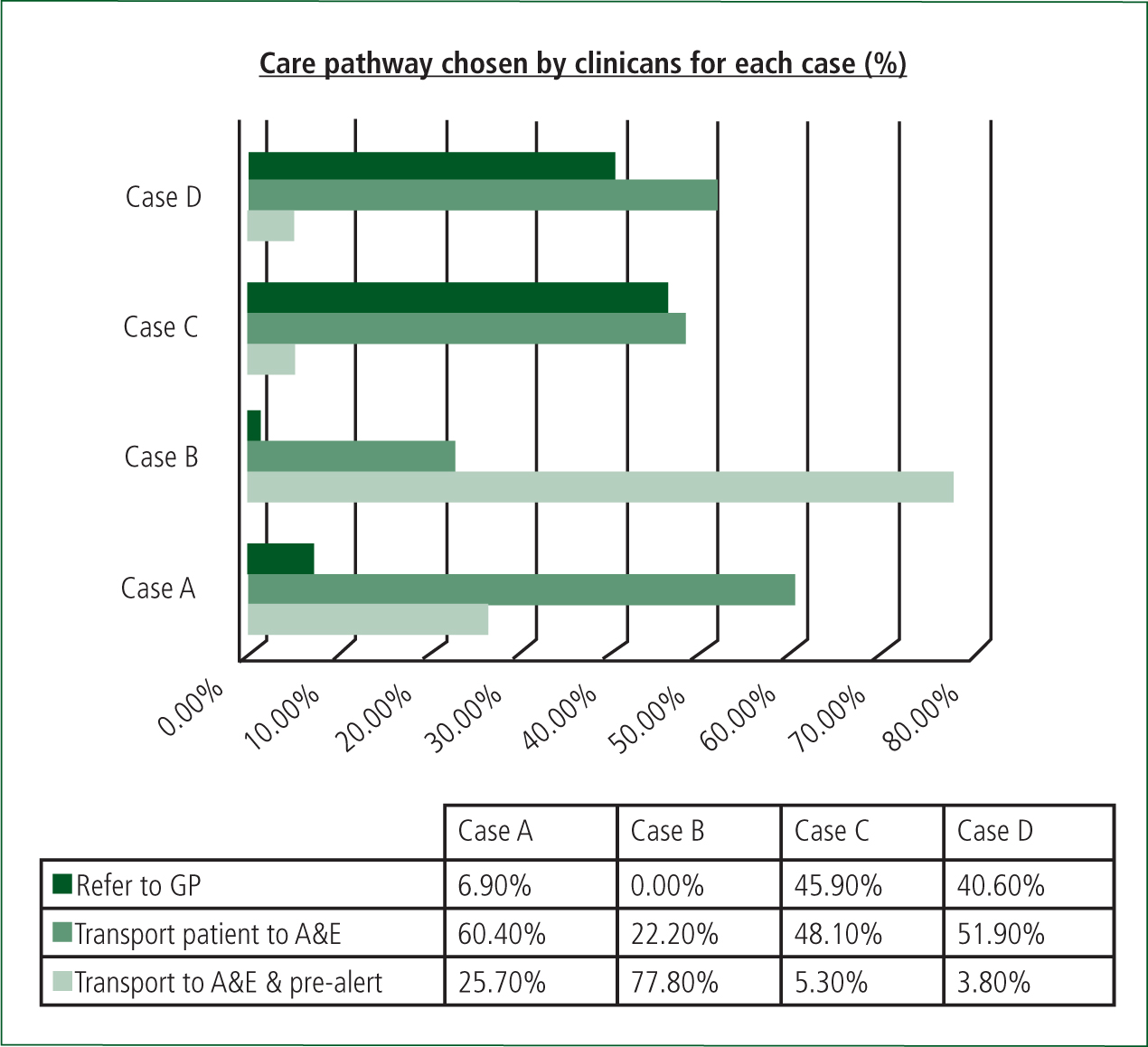

All the cases in the survey met the criteria for sepsis according to a pre-hospital screening tool (Robson et al, 2009), with case B meeting criteria for severe sepsis. Figure 4 shows variability among respondents in all the case studies with regard to care pathways.

Discussion

To date, the SSC has not involved the pre-hospital field in its guidelines. It has become apparent that recognising the symptoms and treating severe sepsis and septic shock early improves prognosis (Studnek et al, 2012).

In this study the knowledge and the views of pre-hospital clinicians has been observed to ascertain what is currently known. No other study has looked at pre-hospital clinicians' views. This study has investigated if pre-hospital clinicians are confident in their knowledge of sepsis, if they would use a sepsis screening tool above clinical acumen and highlight any training needs.

With regard to clinicians' knowledge levels there are fairly wide confidence intervals suggesting poor precision. However, the upper and lower limits both indicate that a substantial percentage feel like they do not have a good knowledge of sepsis. Considering 70% of respondents had undertaken statutory and mandatory training this is an alarming amount. The rest of the staff that stated they had not had employer training had an opportunity to, and are required by the Trust to view a ‘patient care update’ regarding sepsis that was made available in July 2013.

Sepsis is not currently taught on student paramedic programmes. Practically all (98%) of the respondents said they would like to receive further training on sepsis. Interestingly, when clinicians were asked whether they felt training was adequate 46% said no. Training was, however, associated to knowledge and awareness of the SSC. The statutory and mandatory training delivered was the same for all staff levels in the Trust from emergency care support workers, advanced technicians and paramedics. Due to the differing levels of care provided by each staff group, improved confidence in knowledge may be achieved if future training is aimed at skill level rather than a general training course for all staff. Considering the high frequency that septic patients are transported by EMS (Seymour et al, 2010; Studnek et al, 2012; Grey et al, 2013) with the number been reported as high as 88% (Gray et al, 2013), providers of paramedic education should consider its inclusion on further programmes and further training for staff is urgently required.

In a recent audit within NEAS (McClelland and Younger, 2013), sepsis cases were reviewed (unconfirmed by emergency departments) that were pre-alerted to hospitals by staff before and after statutory and mandatory training. In their results, less than half of the pre-alerted cases met the criteria for severe sepsis. In this study, case B is the only case that meets the criteria for severe sepsis. Encouragingly, all respondents indicated they would transport case B to the emergency department, with 77.8% indicating they would pre-alert ahead; however, this leaves a reasonable proportion not pre-alerted, potentially delaying EGDT initiation. Generally, there was little consistency with the referral pathways chosen by respondents (Figure 4). Brown and Bleetman (2006) highlight that the decision to pre-alert a hospital or not is based on experience and clinical acumen. Experience and qualifications of the respondents is well distributed and there was no significant difference between the respondents' views on their knowledge with education level or years of experience, therefore in regards to this study it could be considered lack of knowledge on sepsis may contribute to the varied decisions made by clinicians. Despite the lack of confidence in respondents' knowledge, when recognised, awareness of the severity of the condition and the benefits of quick interventional therapy is appreciated among staff. The results highlighted 94% of respondents thought that emergency departments should treat sepsis immediately or within the first hour.

Robson et al (2009) have recommended the use of a screening tool specifically for sepsis can improve outcomes. 97% of respondents indicated that they thought a screening tool would help identify patients and 98% stated they would use a tool alongside clinical acumen. Feedback on how to best implement a screening tool was predominantly its inclusion in the JRCALC pocketbook or as an addition to the electronic patient report form (EPRF). Future software updates for electronic reporting should consider this for subsequent versions. The importance of getting patients to definitive care within the first hour (or golden hour) is not a new concept to pre-hospital clinicians. In trauma care literature ‘the golden hour’ justifies much of the current trauma system (Lerner and Moscati, 2001). Brown and Bleetman (2006), Fullerton et al (2012), and Subbe et al (2001) have also recommended modified early warning scoring (MEWS) to assist in the identification of critically ill patients. The results of this study support its use when deciding to pre-alert a patient to emergency departments to ensure consistency among clinicians.

Limitations

This study only surveyed pre-hospital clinicians in the North of England and so cannot be generalised to all pre-hospital staff. All pre-hospital clinicians were invited to take part to maximise the response rate and voluntarily responded, which introduces self-selection bias.

When staff were questioned about training adequacy it should be considered that there were 41 ‘none’ responses. This could be due to the fact that 42 of the respondents had not undergone the statutory and mandatory training, or it is possible this transpired to be a question of sensitive nature.

Overall, the response rate was low. Due to the varied response of years in service and education level of the population it is not anticipated to be only due to sampling bias. Initial feedback was that there was not enough time to sit at a computer and complete the survey when at work, and home access facilities would not allow external links to be viewed. Another problem with recruitment was that demographic information held by the Trust was out of date. This became apparent when distributing the paper versions of the survey to staff.

While this study was running another survey based study was also being undertaken in the Trust (S Monaghan, unpublished observations). This could have affected the number of respondents entering this study. Interestingly, the response rate in the other study was also around 20%. To maximise involvement in future research within ambulance Trusts, barriers should be explored further to ascertain the best way of delivering surveys to staff.

An original survey design was used for this study. Although the survey was piloted among a small number of staff before distribution, having contemplated the results on a larger scale, stratification of respondents and avoidance of sensitive questions would be considered in further survey designs.

Conclusions

Pre-hospital clinicians appreciate the severity of sepsis and the importance of recognising it and treating it quickly. Knowledge levels differentiate among the cohort and practically all clinicians state they require further education. Addressing the training needs of pre-hospital clinicians will aid towards ensuring the best care is delivered to septic patients.

Clinicians state they would use a screening tool to assist with the identification of sepsis when assessing patients and would prefer it on the EPRF or pocketbook JRCALC. Further research is required to validate a sepsis screening tool for pre-hospital use.

Owing to the low response rate, an investigation into barriers in pre-hospital research would be beneficial for future studies of this design.