Mental health problems are common within our society, with one in four experiencing problems in their lifetime (Rethink Mental Illness, 2015). Depression is listed as the second most likely reason that people visit their GP after respiratory problems (McCormick, 1995; Ustun and Sartorius, 1995). NHS England (2014) estimate that mental health costs the NHS £100 billion each year. As the majority of patients seek help in primary care situations, it is likely that ambulance staff will have frequent contact with patients presenting with mental health problems, particularly those in crisis. There is a higher incidence of borderline personality disorder in the the clinical population and it has been found to be four times higher in those attending primary care, indicating likely and frequent contact with GPs (Leichsenring et al, 2011).

This article was inspired following a particularly challenging 999 telephone triage carried out by the author with a patient who had a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. Although the patient's reason for contacting the emergency services related to a medical concern, the triage was overly prolonged, complex and derailed at frequent points when the patient appeared to completely withdraw and stop engaging with the triage process. As a result, the author was motivated to discover more about borderline personality disorder and see if they could have adapted their responses to improve rapport building and maintain trust.

Diagnosis

Borderline personality disorder is termed a ‘serious psychiatric disorder’ (Perseius et al, 2007) and is associated with a high rate of suicide. It is associated with transient mood shifts, distressing feelings, instability in relationships, risk taking behaviour or self-harm, poor impulse control and poor self image. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) report that: ‘Personality disorders are associated with ways of thinking and feeling about oneself and others that significantly and adversely affect how an individual functions in many aspects of life’ (APA, 2013). Diagnosis is based on assessing pervasive patterns of unstable behaviour, poor self image and difficulty managing interpersonal relationships.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4 (APA, 2012) requires that five or more of the following traits are required for a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder:

It is most likely that symptoms present in late adolescence and early adulthood, and once recognised and treated it is encouraging that most patients experience relief of symptoms and experience good psychosocial functioning. It is likely though that the majority of patients will lose this level of functioning over time and not regain it (Leichsenring et al, 2011).

Numbers diagnosed

There is some debate about the incidence of borderline personality disorder in the general population; most figures are between 1–2% (Leichsenring et al, 2011; Borschmann et al, 2012; MIND, 2012), which is similar to the incidence of schizophrenia (1%) in the general population (NHS Choices, 2014b). It is likely that patients with borderline personality disorder may also have other mental health or behavioural conditions, such as alcohol or drug misuse, depression, anxiety or other personality disorders.

Stigma

As there is a likelihood of multiple crisis episodes, it is possible that patients with borderline personality disorder may present recurrently to the ambulance service. These patients may also have a history of disengagement with treatment pathways or sporadic commitment to treatment, as poor self-motivation is a symptom of the condition (McNee et al, 2014). As features of the condition relate to one's personality, the symptoms can often be challenging and vexing to the clinician (recurrent suicidal behaviour or instability of mood, sudden and unpredictable disengagement).

Paris and Black (2015) argue that stigma attached to the condition can mean it is seen in a less favourable light by clinicians when compared to other disorders such as bipolar disorder. They also note that the behaviour of patients with borderline personality disorder can be interpreted to be more ‘attention seeking’ than other patients and therefore ‘less mentally ill’ than patients with other diagnoses (Paris and Black, 2015). In a survey to assess the attitudes of mental healthcare staff towards patients with borderline personality disorder, James and Cowan (2007) found that most staff (80%) found it more difficult to care for patients with borderline personality disorder than those with other conditions. There can be further stigma attached to the diagnosis through the use of the term ‘personality disorder’ as this can be interpreted to mean a defect of the ‘self’ or of that patient's identity. In order to reduce distress to patients and limit a critical overtone to assessment, Hawley et al (2011) suggest using the term ‘personality difficulties’ when discussing the condition with patients.

Causes

As with many psychological disorders, the causes of borderline personality disorder are unclear. It is thought to be a combination of genetic and environmental factors.

Environmental factors

It is reported that 8 out of 10 patients with BPD experience parental neglect or abuse in childhood (NHS Choices, 2014a). BPD patients also report significantly more adverse events in their childhood than those with other personality disorders (Schulz et al, 2008). When looking at the impact of childhood trauma, McNee et al (2014) note that maltreatment in childhood can have implications for the patient's ability to regulate behaviour, impair attachment and go on to affect the patient's ability to communicate when in times of distress, as the patient has limited experience of reassurance that difficulties can be overcome. Patients with traumatic childhood experiences may have no experience of reliable support during times of stress and later find it hard to regulate their responses and behaviour to subsequent periods of difficulty or perceived stress.

Genetics

Studies have shown a significant heritable component to the development of most mental disorders (Jang et al, 2005). Studies involving identical twins show there is a two in three chance of the second twin developing BPD if the first receives a diagnosis (Pascual et al, 2008). However, if we are aware that genetics play a role in determining personality traits, we are also aware that there is no specific gene identified as ‘causing’ borderline personality disorder. One should also be aware that if we know environmental factors play a part in the likelihood of borderline personality disorder it is very likely that identical twins will have experienced the same environmental factors growing up.

Neurobiology

Studies involving MRI scans of the brains of people with borderline personality disorder show increased activity of the amygdala (regulates emotions such as fear and anxiety) when responding to slides of human emotional facial expressions (Levy et al, 2006; Nosè et al, 2006). There have also been changes to the structure and function of the hippocampus (helps regulate behaviour and self-control) and pre-frontal cortex (planning and decision making) (Paris and Black, 2015) in MRI studies.

Neurotransmitters

Changes to dopamine and noradrenaline neurotransmitters have been associated with some patients with borderline personality disorder (NHS Choices, 2014a). Altered function of the neurotransmitter serotonin is also thought to affect mood, the ability to control urges and aggression and depression.

Suicide, crisis and risk

The Office for National Statistics recorded 4 513 deaths attributable to suicide in 2012 (Department of Health, 2014). The NHS estimate that 60–70% of people with borderline personality disorder will attempt suicide at some point in their life. Perry (1993) reports that 10% of patients with borderline personality disorder will die by suicide over a 20-year period. To underplay the risk of suicide for BPD patients and their families and to underestimate the importance of appropriate crisis intervention for these people is ‘potentially lethal’ (Borschmann et al, 2012). We know that patients in crisis with BPD are likely to present to the emergency services when suicidal or self-harming, and we know that the likelihood or recurrent crisis is high (Binks et al, 2006). Avoiding complacency when assessing patients is critical as there is a real possibility that the clinician may feel inoculated to the patients needs if they have assessed them and their risk previously, or if the patient is known to present frequently in crisis (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NCCMH), 2009).

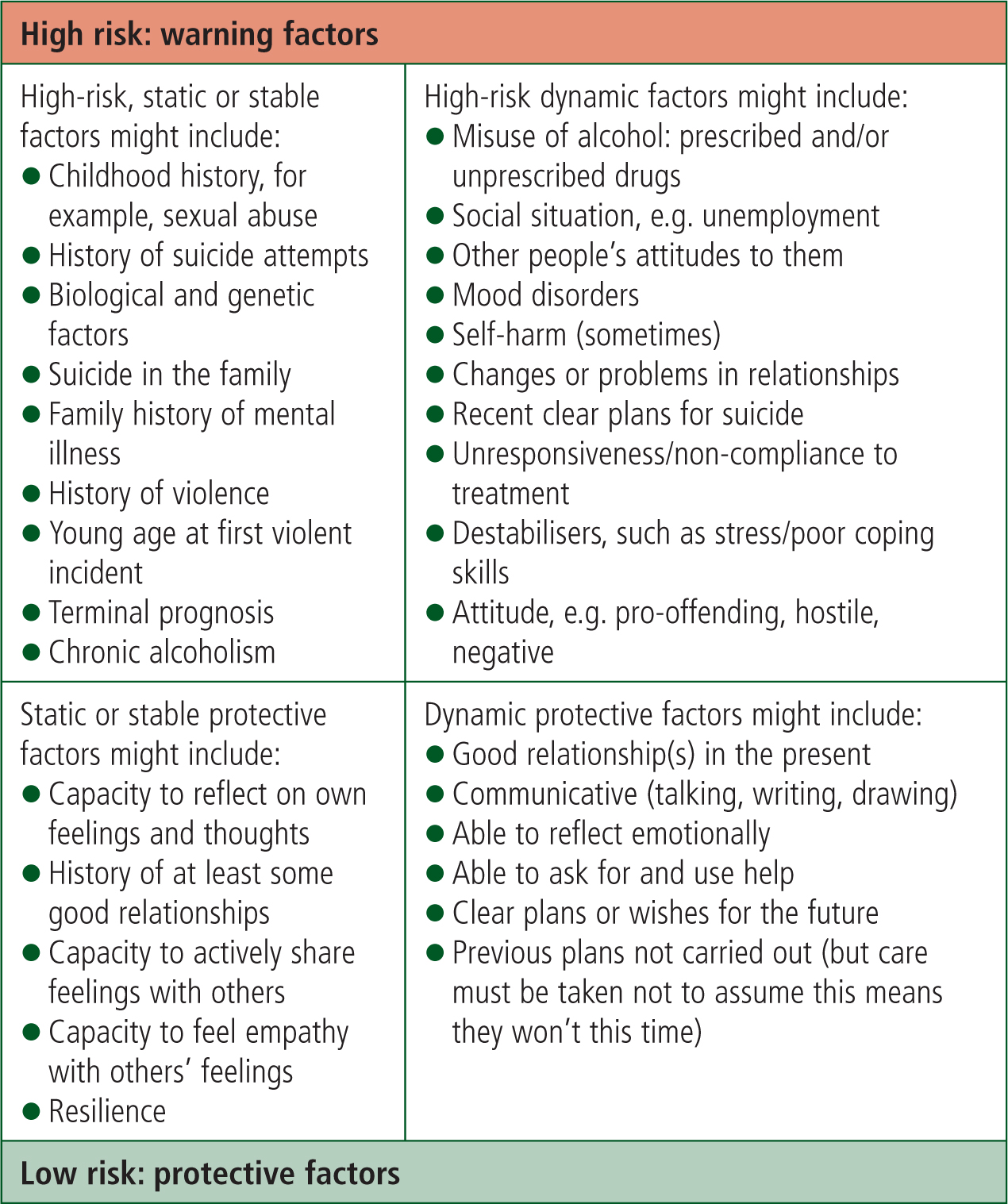

The challenge to the clinician is to assess the patient's risk of harm to themselves or others and find a way of managing the crisis. All self-harm gestures and suicidal actions need to be immediately assessed. It is difficult for the pre-hospital clinician to develop strategies with the patient as there is often no access to the patient's care plan or limited access to specialist services out-of-hours. A balance must be struck between promoting autonomy, empowering decision making and avoiding harm against the need to intervene (NCCMH, 2009). Hawley et al (2011) encourage paramedics to engage with patients with optimism and hope and seek to find solutions that will encourage coping skills. Yeandle (2013) describes the phenomenon of BDP patient's feeling that risk and the assessment of risk to be the most important factors in the allocation of their care. Continuing with risky behaviour then becomes an essential way of patients communicating the distress of their needs. In order to avoid the concept of risk assessment becoming a commodity for patients she argues that risk assessment must be completed with the patient themselves as opposed to something that is done to patients. Using a risk matrix with a patient can help explore patterns of behaviour, strategies and causes for self-harm (see Figure 1).

The NCCMH (2009) guideline for borderline personality disorder lists five key aims for those assessing patients presenting in crisis:

Brimblecombe et al (2003) note the key reason for admission to hospital to be risk to self (53.2%), followed by risk to others (11.3%) and carers unable to cope (8.1%). While examining factors that may predict admission, they highlight high suicidal ideation and previous hospital admissions as the key predictive variables affecting admission rates.

Treatment

For those receiving a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder there is limited evidence that drug therapy is beneficial. NCCMH (2009) do not recognise or recommend any drug therapy for the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Cautious use of sedative medication may be considered on a very short-term basis if the patient presents in crisis, e.g. one week of low-dose medication with assessment of the risk of overdose and post-crisis review arranged.

The NHS advocates treatment and support from community mental health teams (CMHTs) who aim to provide support and care while promoting independence for patients. Forms of psychotherapy are often discussed after diagnosis. Three common therapies are: dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT), mentalisation-based therapy (MBT) and therapeutic communities (TCs) (NHS Choices, 2014a).

Best practice

The NCCMH guideline (2009) formalises the gold standard of treatment for patients with BPD in the UK. The central principles outline the need to ensure that no patient should be excluded from any health or social care setting based on their diagnosis or because they have self-harmed. A patient's right to involvement and autonomy in decision making is recommended in order to engage patients and provide them with choices about their care, information about the life choices available and the consequences of those choices. It asks that patients ensure, ‘they remain actively involved in finding solutions to their problems, including during crises’ (NCCMH, 2009). Binks et al (2006) remind us that BPD patients will often find engaging in treatment plans difficult, and as a consequence, frequently present to health services when in crisis (Borschmann et al, 2012). Although the NCCMH guideline does not specifically address the role of the ambulance service in providing crisis care, it does recommend that staff in primary care who are significantly involved in the assessment and early treatment of people with borderline personality disorder are provided with training, ideally from a specialist personality disorder team.

The aim of crisis management should be to assist the patient to return to a more stable level of mental functioning. A supportive and empathic attitude is reported as being of particular benefit if initial contact is made by telephone (NCCMH, 2009). This is particularly pertinent with the increase of ‘hear and treat’ and phone triage services, such as those provided by the ambulance service and 111 service.

When faced with a difficult service user with BPD, McNee et al (2014) identified causes of frustration that seemed to impair the patient's progress. The patient involved had been assessed multiple times, had little motivation to change her behaviour, participated sporadically in treatment, did not adhere to agreed boundaries that were set, and frequently disengaged with therapeutic relationships when fearing abandonment. McNee's team sought to overcome their feelings of inadequacy when dealing with the patient by developing a consistent team response to the patient's behaviour. Staff were encouraged to help the patient reflect on and understand her perceived distress without judgement.

A service user with BPD requests that staff follow basic principles of patient care and notes: ‘Responses don't need to be that profound or from people with a lot of experience of working with this disorder, they just need to be human’ (NCCMH, 2009). The service user later expands on how a calm, reassuring attitude were helpful in ascertaining the cause of the problem, but highlights how the structuring of questions can elicit better responses from someone struggling to control overwhelming feelings of distress:

‘A few gentle questions helped, not, what I call, big questions such as “How can I help?’”or “What's happened?”, but smaller questions such as “I can hear you're upset, how long have you been feeling like this?” Big questions such as “How can I help?’”or “What's wrong?” always feel to me too overwhelming and too difficult to find a starting point’

The NCCMH guideline (2009) advises staff to adopt the following approach:

Limitations

There is very limited primary research available to assess attitudes of ambulance staff in relation to borderline personality disorder and this is beyond the scope of this article. Further research involving ambulance staff should consider prior training, ‘on the job’ experience of dealing with mental health crisis and how ambulance staff overcome problems during triage and treatment of those with BPD. There is also scope for exploration of the patient's experience after having contact with the ambulance service.

Conclusions and recommendations

It is clear that assessing and supporting patients with borderline personality disorder can be daunting; particularly if the clinician has little or no knowledge of the disorder and its likely characteristics. Understanding the condition provides insight into what can be seen as problematic or rebellious behaviour traits as a means of coping strategy for the BPD patient. Features such as behavioural disturbance, impulsiveness, intense anxiety, frequent self-harm, oscillating engagement and disengagement, emotional reactivity, varying receptivity of the patient to help, inconsistent relationship behaviour, risk taking and poor self image are complex and sometimes difficult to understand.

A person with borderline personality disorder may also have other comorbid conditions (Leichsenring et al, 2011) and present frequently for help from the emergency services when in crisis (Hawley et al, 2011). Ambulance staff are highly likely to come into contact with patients who are feeling suicidal or self-harming. Patients with borderline personality disorder are at high risk of suicide and may present multiple times in crisis.

Complacency when assessing frequently presenting patients is potentially catastrophic and attempts should be made by ambulance staff to assess each presentation on its own merits. It is noted that many mental health staff trained to deal with borderline personality disorder find it difficult and frustrating; acknowledging that staff often find these patients harder to care for (James and Cowman, 2007) and are dismayed or disappointed with slow recovery or seeming lack of progress (McNee et al, 2014). Acknowledging these feelings helps drive change in the workplace in order to provide better understanding and engagement from service users.

Assessing risk with patients who are suicidal or self-harming is vital and the use of visual aids, such as the Risk Assessment Matrix, provide clinicians with a structure and checklist when dealing with patients in crisis. Developing a supportive and non-judgemental rapport with the patient fosters a more productive relationship and ambulance staff are encouraged to structure questioning in a way that allows the patient to focus on their current concerns and find ways of coping.

Specialist training for ambulance staff is not routinely offered, though would be clearly beneficial given the high probability that ambulance staff will treat patients with borderline personality disorder. There is very little current research or training packages available for ambulance staff in dealing with patients with BPD.

There is evident scope for further research to be commissioned in relation to understanding the role of the paramedic in crisis management, as well as qualitative studies of attitudes of ambulance staff to service users with BPD and vice versa. The scope of this article is to introduce ambulance staff to the condition in the hope that subsequent interactions with patients with BPD will be better informed and tailored to understanding the patients complex condition.