Sepsis kills between 36 000 and 64 000 people in the UK every year (Daniels, 2011), with a prevalence ranging from 1–3 per 1 000 population, increasing in rate over the last two decades (Seymour et al, 2010). Severe sepsis with hypotension has a rapidly evolving negative clinical course with mortality increasing by 7.6% for every hour's delay in the administration of antibiotics (Kumar et al, 2006). These patients have an episode mortality of around 31% (Daniels, 2011) but lack the clear, rapid and carefully audited pre-hospital pathways successfully developed in recent years for other critical conditions such as myocardial inraction (MI) and stroke (Wang et al, 2010)

Early sepsis treatment is both simple and effective (Daniels, 2011; Ferrer et al, 2014 among others). Delivering a bundle of early interventions (The Sepsis Six—Box 1) can significantly improve survival (Seymour et al, 2012; Rivers et al, 2012; Ferrer et al, 2014). Improving the recognition of sepsis and rapid delivery of these life-saving interventions has the potential to dramatically improve morbidity and mortality (Rivers et al, 2001; Nguyen et al, 2007; Boardman et al, 2009; Siddiqui et al, 2009; MacRedmond et al, 2010; Gaieski et al, 2010; Rivers et al, 2012). Despite these dramatic figures, however, it has so far proved frustratingly difficult to significantly improve timings for in-hospital sepsis treatment.

Paramedics may have a unique opportunity to improve sepsis treatment (Boardman et al, 2009; Robson et al, 2009; Wang et al, 2010; Seymour et al, 2012; Guerra et al, 2013). Around 3.3% of all US ambulance attendances are for severe sepsis (Seymour et al, 2012) and emergency medical services (EMS) often triage and attend septic patients well before any other clinician (Wang et al, 2010; Seymour et al, 2012; Groenewoudt et al, 2014). Despite this, the pre-hospital phase of sepsis is poorly studied and international mortality figures take little notice of the many complex variables and interactions that take place before patients arrive in hospital. It is possible that outcomes could be significantly improved if paramedics were equipped to intervene in this largely unstudied pre-hospital phase to provide diagnoses and commence early treatment with evidence-based interventions.

The complexity, however, of the pre-hospital environment, the reliance on telephone triage and computer aided dispatch, the variable presentations of sepsis and concerns surrounding the over-delivery of antibiotics all serve to complicate the creation of new pre-hospital sepsis pathways. Overcoming these challenges to provide safe, accurate and timely paramedic sepsis treatment may significantly improve patient outcomes but a number of obstacles stand in the way. These perceived hurdles centre around the ability of paramedics to accurately and consistently diagnose sepsis using clinical judgement and in the absence of biochemical and haematological tests. If it can simply be shown, however, that sepsis can be accurately diagnosed and safely treated by paramedics the door will have been opened to a comprehensive ‘call to needle’ approach, where the complex pre-hospital phase of sepsis is at last incorporated into sepsis management pathways.

Methods

The Pre-hospital Piperacillin/Tazobactam (PrePip) project tested the concept that UK paramedics could accurately recognise sepsis, aseptically take blood cultures, and safely and rapidly treat septic patients before they reached the ED. PrePip aimed to fully integrate sepsis care across the pre-hospital and in-hospital phases, providing key aspects of the Sepsis Six in the community for high-risk patient groups.

Two initial target groups of patients were considered eligible for inclusion in the project: adult patients on or recently finished cytotoxic chemotherapy (Group 1), and those with a urinary catheter and showing signs of urosepsis (Group 2). These two groups were chosen as they had a higher incidence of sepsis, often with a rapidly evolving course and poor prognosis and therefore had a high potential to benefit from the enhanced service. The aim was to pilot the project with these two clear and well-defined groups before considering expansion to other septic patients.

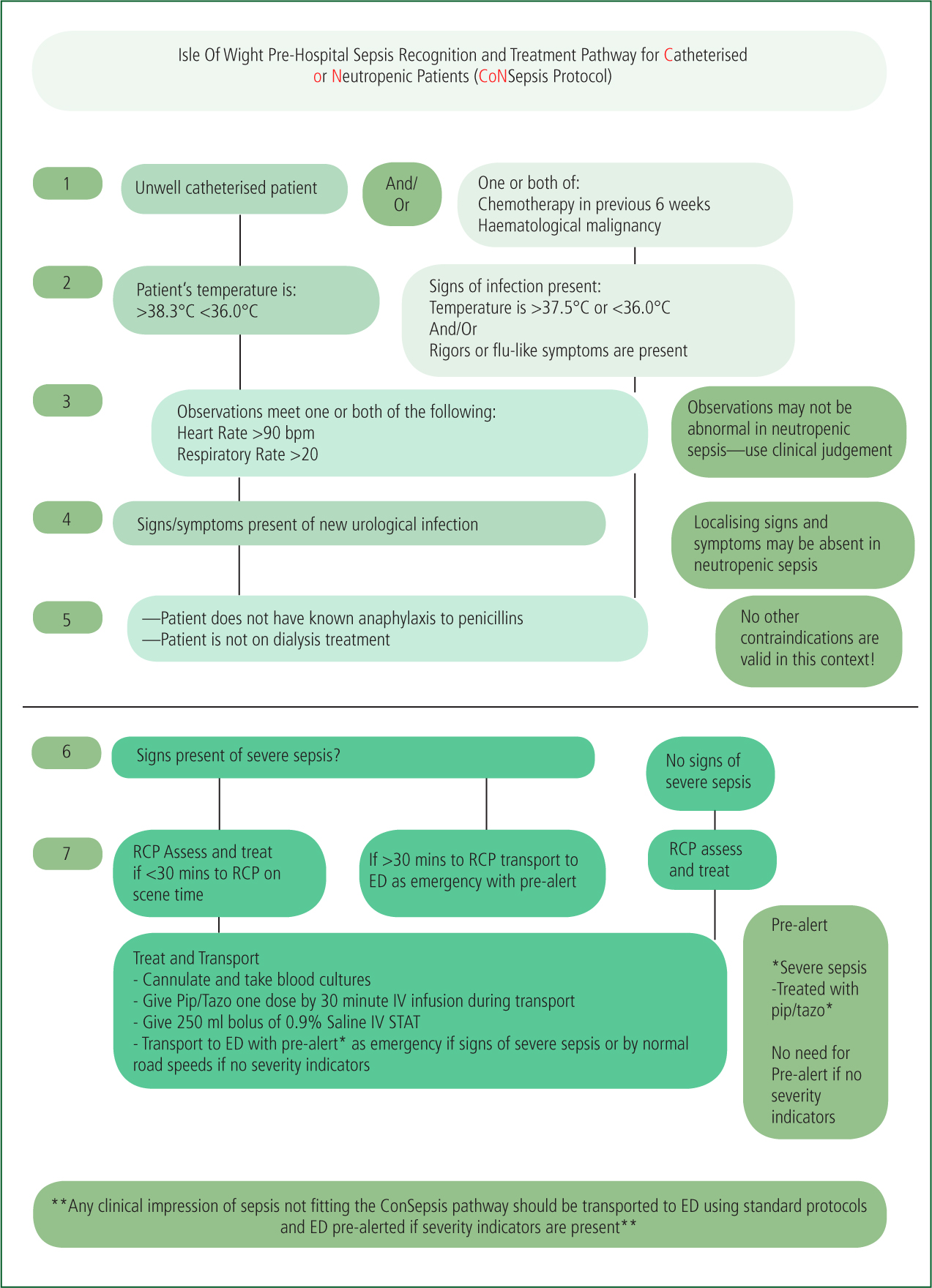

A new patient group directive (PGD) was developed for paramedic use of piperacillin/tazobactam (Tazocin) a broad spectrum, bactericidal, penicillin-based antibiotic. With microbiology and pharmacy support a protocol for delivery of this treatment by paramedics was devised with an accompanying standardised operational policy for eligible patients. (CoNSepsis protocol—Figure 1)

A new flowchart protocol for paramedics was developed to give clear guidance regarding eligibility and treatment of potential sepsis patients. This utilised a diagnostic tool incorporating elements of the Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) criteria and consideration of an infection source (Figure 1). Group 2 patients were treated if they were found on assessment to have signs of SIRS, including a temperature of ≥38.3°C or ≤36.0°C accompanied by a tachycardia ≥90 bpm and/or tachypnoea ≥20 bpm and clinical symptoms or signs of urological infection. Due to the often non-descript nature of early sepsis in patients undergoing chemotherapy, Group 1 patients were treated if they had a temperature ≥37.5°C or ≥36.0°C and/or signs of infection such as rigors of flu-like symptoms. Group 2 patients also needed to present with a tachycardia ≥90 bpm and/or tachypnoea ≥20 bpm. For both groups of patients the only contraindications to treatment were known anaphylaxis to penicillin or severe active renal failure requiring dialysis (Figure 1).

Paramedics received face-to-face training from ED doctors and specialist microbiology pharmacists in recognition of sepsis in these two groups and practical training in delivering the interventions of taking blood cultures and delivery of the intravenous antibiotics. In addition, ambulance control centre clinicians and dispatch staff received training in the new protocols. Ten paramedics were initially trained to deliver the PrePip interventions but this number was expanded after the first 6 months of the project.

Group 1 and Group 2 patients were identified by paramedics when responding to calls. In addition, potentially appropriate patients were identified by the district nursing teams and the regional chemotherapy unit respectively. Patients receiving chemotherapy were given written and verbal advice at the start of their chemotherapy reflecting these new procedures. This amounted to a change from advice to call the chemotherapy unit to advice to call 111/999 for advice when pyrexial (≥38°C) or if encountering flu-like symptoms within 6 weeks of chemotherapy.

Each case where the PrePip trained resource was engaged was reviewed and the patient followed up in the hospital records for a minimum of 30 days. The in-hospital diagnosis was determined from their records and their outcomes were ascertained.

The project started clinically on 20 September 2013 and ran for one year.

Results

Seventy patients were treated by paramedics in the first year of the project, with 45 Group 1 (chemotherapy) and 25 Group 2 (urosepsis with indwelling urinary catheter) patients treated. Average patient age was 73 years with 55% female and 45% male.

Sepsis diagnosed by paramedics continued to be the working diagnosis with intravenous antibiotics continued by inpatient consultant-led teams in 59/69 (86%) of cases. Overall, 8/69 (11%) of patients selected for PrePip treatment by paramedics were subsequently discharged directly from ED without admission and without a diagnosis of sepsis, but follow-up of these cases revealed 5/8 of these direct ED discharges re-attended within 5 days to be admitted and treated for sepsis. In the 69 patients where sepsis was diagnosed by the paramedic the hospital diagnosis following conveyance was confirmed as sepsis in 64 of the cases. In the remaining five cases alternative diagnoses were subsequently made. Overall paramedic diagnosed sepsis patients treated under the PrePip protocol had their diagnosis corroborated by inpatient medical teams in 64/69 cases (93%).

Average time from call (999 or 111) to antibiotic delivery for treated patients was 49 minutes 25–125 minutes). The average call to on-scene time was 16 minutes (1–46 minutes). Paramedics assessed, cannulated, took blood cultures, reconstituted and gave antibiotics in 35 minutes on average (14–120 minutes) with an increase of 5 minutes over the average on-scene time and cycle time for the ambulance service.

Paramedic-taken blood cultures grew possible skin contaminants in three cases (4.3%)—a rate similar to the in-hospital figures for blood cultures taken by doctors.

Discussion

Results from the PrePip project showed that paramedics were able to make clinical decisions based on a simple protocol that were in close agreement with subsequent in-hospital consultant diagnoses.

PrePip was, however, only a small service development project in a well-integrated healthcare system in the South Coast of the UK. The relevance of the results to the rest of the UK are therefore unclear. We do believe, however, that it can be concluded from this project that UK paramedics are capable of accurately identifying sepsis in key groups and of giving life-saving early treatment. As discussed above, our analysis of the data and our ED audits show that this approach strengthens and improves the speed of delivery of sepsis interventions even for those not falling within the treatment parameters of the project. Paramedics were able to take blood cultures aseptically with minimum contamination prior to antibiotic delivery and hospital arrival. Antibiotics were reconstituted and administered without any untoward incidents or reactions. Concerns about over-prescription of antibiotics were not realised and our experience during the project was that antibiotics were not over-utilised by paramedics when compared with emergency department and in-patient practice.

These interventions were delivered with minimal increase in cycle times (time on scene) or delay in movement to hospital. It was always expected that paramedics would require more time on scene to enable the interventions to be delivered but it was unexpected that this would be as little as 5 minutes.

It should also not be overlooked that projects such as this have a large impact on the profile of conditions. The project had a major positive influence on emergency department treatment for both PrePip patients and those not treated under the PrePip protocol. This collateral finding was substantiated by a significant improvement in the emergency department's recorded performance in the national College of Emergency Medicine audit of ED sepsis treatment in 2014 (compared with 2013) (Figure 2). We believe this is partly to do with the increased profile of sepsis in our hospital due to the unique nature of the project but in the main part is a direct response to the robust recognition, prioritisation, pre-alerting and increased expectations of our paramedics. With our paramedics now firmly set up as well-trained sepsis champions, medical and nursing staff are more acutely aware of the need for rapid treatment.

X axis—Number of septic patients; Y axis—Time to antibiotic delivery in minutes.

It is our opinion that many of the perceived obstacles to paramedic sepsis treatment are surmountable with careful selection of patient groups, robust paramedic training in sepsis recognition, and modification of ambulance call handling procedures in 999 and 111 services. We acknowledge, however, that there would be significant challenges in delivering a similar model in areas with less tight integration of ambulance 111 and 999 services, chemotherapy services, district nursing and acute hospital services. Additionally, there would be challenges to achieving this approach across large geographical areas with multiple services and different commissioning strategies. For chemotherapy (Group 1) patients, wholesale change in emergency pathways is required to deliver such a project. For other types of sepsis, however, no such culture change is required in order for ambulance clinicians to deliver the key elements of the Sepsis Six.

The challenges of diagnosing and treating sepsis in the pre-hospital environment without access to biochemical tests require complex balancing of risk and benefit. Paramedics are, however, skilled in using clinical decision-making to identify specific illness and to stratify risk. Therefore we would advocate a sepsis culture change and we foresee the adoption of ‘call to needle’ targets for delivery of antibiotics for potential sepsis cases as for thrombolysis, bringing the complexities of the pre-hospital environment into sharp, auditable focus.

Limitations

PrePip was designed as a service development project and not as research. For this reason it is not powered to answer questions relating to mortality or morbidity reduction or to directly compare treatment groups with previous practice. It is also important to note that the Isle of Wight has a very clearly defined healthcare population with tightly integrated services and all controlled centrally by one single NHS Trust that incorporates hospital, ambulance and community services. For this reason many of the potential difficulties of setting up a project like this are more easily surmountable. We believe, however, that it should be possible for paramedic sepsis treatment to be delivered with the backing of the local hospital Trusts and microbiology departments and the perceived organisational barriers to this type of service development are all surmountable. Paramedic sepsis treatment requires investment in paramedic training and support; however, this is likely to be manageable with minimal cost in terms of operational or training time.

PrePip treated only higher risk patients from two clearly defined groups. It could therefore be argued that paramedics may be unable to accurately diagnose sepsis in a more general population. This concern is not, however, borne out by this project. Observationally it became clear throughout the project that sepsis was being diagnosed accurately and consistently by paramedics even in the non-treatment groups with major collateral improvement in the treatment timings of all septic patients brought to the ED by ambulance. For this reason, earlier this year, we chose to expand the project to allow all IOW paramedics to treat sepsis presenting in any adult using a new ‘PrePip2 protocol’. We are looking forward to analysing the results of this expansion and publishing them later this year.

Conclusions

Given the potential impact of even short delays in initiating antibiotic treatment for sepsis and the difficulties of achieving timely antibiotic delivery once in hospital, it is right that new approaches for the delivery of treatment are explored. Recognising the opportunities for developing a pre-hospital phase for sepsis treatment may prove effective in improving overall care and outcomes. We are satisfied we have shown the potential for paramedics to recognise and treat pre-hospital sepsis for specific groups of sepsis patients with minimal hazard. We believe therefore that local and national policies directed at improving sepsis care should not overlook the potential contribution of paramedics and what may be achieved prior to hospital arrival. Enhancing, formalising and integrating ambulance sepsis policies that include sepsis screening tools, treatment protocols and pre-alert guidelines is likely to have an important impact on sepsis treatment.

It is difficult to imagine any other condition of such international importance, where time is so much of the essence, that has yet to be consistently treated by ambulance clinicians or to have its own pathway clearly defined. Setting up services of this type is undoubtedly complex but the potential benefit to patients of developing pre-hospital sepsis recognition and treatment protocols and empowering paramedics to deliver them may be significant. This is most certainly worthy of further study.