This project began as a piece of academic research for a service improvement project looking at the rationale of monitoring lactate for adults with sepsis in the pre-hospital setting. Paramedics have for some time been at the forefront in contributing to the treatment and improvement in mortality rate of various lifethreatening conditions, such as myocardial infarction and stroke (Small, 2012). The same improvements in patient outcome could be witnessed in sepsis with improved recognition and management (Robson et al, 2009). The proviso for this is that certain aspects of the Sepsis Six screening tool are readily adopted within the prehospital arena (Boardman et al, 2009). However, current pre-hospital sepsis treatment is ad hoc and far from standardised.

Sepsis

Sepsis is a life-threatening condition with estimates of up to 37 000 deaths annually in the UK alone. When sepsis is not treated the mortality rate increases by 8% every hour (Cronshaw et al, 2011). Such patients are very expensive for healthcare systems to manage, with septic patients accounting for 27% of all admissions to intensive care units in England (Small, 2012). Some observers estimate the cost to treat each sepsis patient is between $22 000–$50 000 (Seymour et al, 2010).

Nee (2006) states that the primary cause of sepsis is from chest injury or illness, causing nearly half of all cases, with the remaining cases originating within the abdomen and as a result of urinary tract infections, soft tissue infections as well as in the skin and bones.

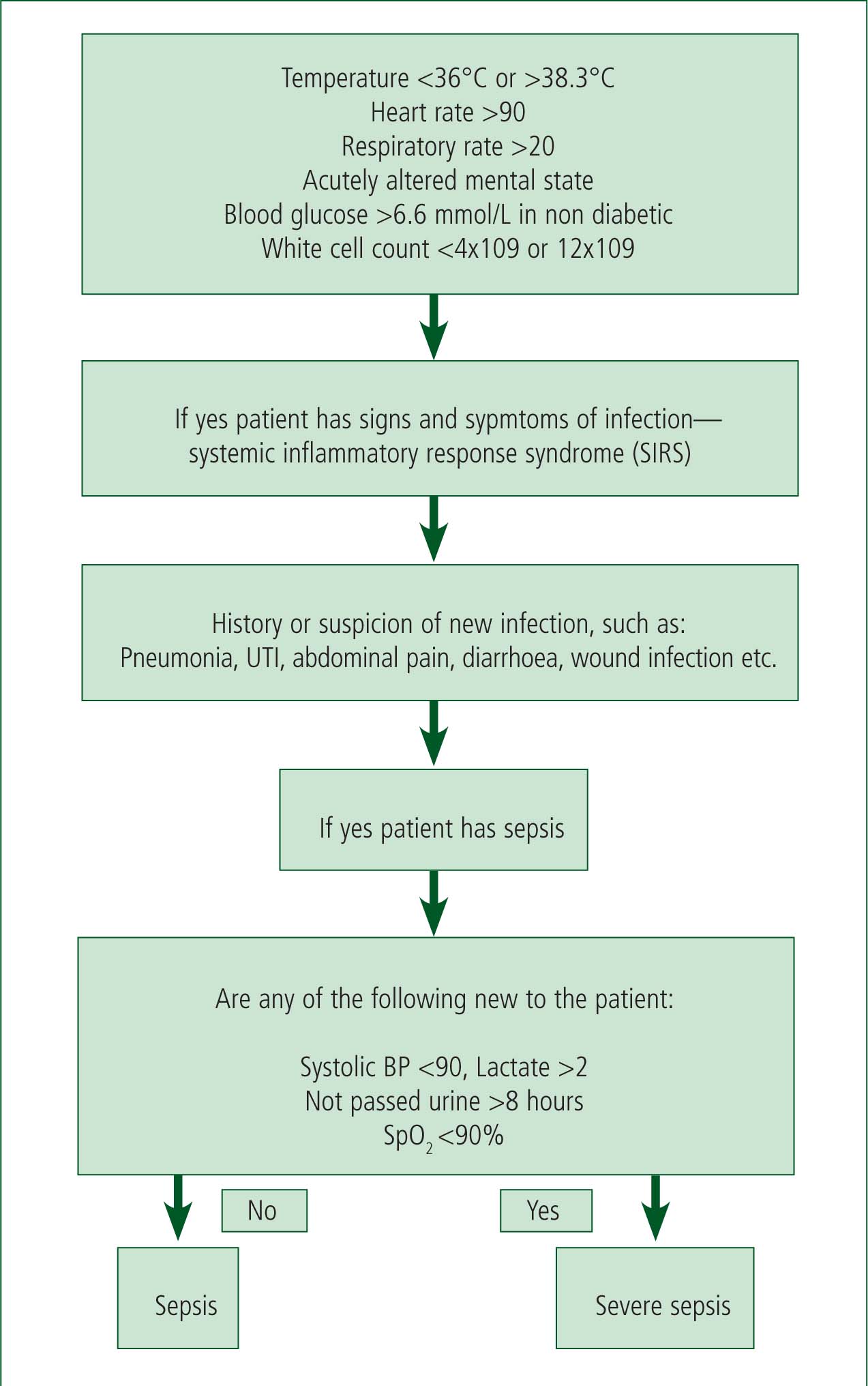

Bacteria can cause a systemic inflammatory response (Small 2012). This response can present as signs of infection known as systemic inflammatory response syndrome or SIRS. Robson et al (2009) use the pre-hospital severe sepsis screening tool as seen in Figure 1.

A patient with any two signs of infection would be SIRS positive (Robson et al, 2009) and when associated with a new infection a patient would be defined as septic (Small 2012). Many patients with sepsis are not unwell but when sepsis continues and the inflammatory response becomes overwhelming the sepsis becomes more severe. Sepsis associated with symptoms of organ dysfunction such as hypotension or increased lactate is defined as septic shock (Boardman et al, 2009) and is associated with an increased risk of mortality.

This high cost to life is unacceptable (Patel et al, 2003). With this in mind, the Surviving Sepsis Campaign aimed to reduce mortality by 25% by recruiting governments and healthcare organisations, and developing standards to recognise and treat sepsis (Slade et al, 2003).

The campaign separated care into two bundles; the first provided by intensive care departments and the second upon arrival at accident and emergency. These bundles are standardised in in-hospital sepsis care.

The first care bundle is known as the resuscitation bundle and is aimed at hospital intervention. The second bundle, sepsis six, comprises oxygen therapy, fluid therapy, intravenous antibiotics, lactate measurement, white blood count measurement and urinary catheterisation (Daniels et al, 2011). This bundle has recently been transferred to the pre-hospital environment to aid in the recognition and treatment of sepsis prior to arrival at hospital. Current prehospital treatment of sepsis revolves around the management of circulation and oxygenation as these are currently the only achievable areas of the sepsis six bundle (Small, 2012).

Method

A PIO (population, intervention, outcome) analysis was carried out on a number of databases. These were Medline, CINAHL, Ovid, Embase and TRIP. Embase and TRIP were found to be most relevant. A less structured search was carried out on ScienceDirect using the strings ‘pre-hospital’ AND ‘sepsis’ AND ‘lactate’.

These strings were altered slightly for the review of the Cochrane Library where pre-hospital was substituted for ‘ambulance’, resulting in one article with some relevance.

An electronic search of the Emergency Medical Journal yielded a number of relevant articles. A hand search was also carried out on The Lancet and the Journal of Critical Care, with relevant data found.

Experts from the World Sepsis Alliance were identified and contacted via e-mail.

An internet search using the strings ‘UK’ and ‘ambulance’ and ‘lactate’ and ‘trial’ was carried out to investigate if any service was currently measuring lactate. One ambulance service was highlighted and was contacted. They were able to provide documentation and some statistics relating to their trial and results so far, which were of interest.

In order to increase the number of results it was decided that reference harvesting may be of some benefit (Horsley et al, 2011).

As a result, a number of relevant articles were found in the reference lists of some journals and these had specific applicability. The limitations of reference harvesting and the dangers of bias from the same authors were appreciated (Horsley et al, 2011).

It is acknowledged that because reference harvesting was necessary it demonstrated that research in this area is limited, and that a different search strategy may be beneficial.

Lactate

When in a hypoperfused state the body is suffering from tissue hypoxia, which in turn leads to an increased level of lactic acid, also known as hyperlactataemia. Lactate is a natural by-product of a lack of oxygen which in a healthy person would be excreted. An elevated lactate level indicates lactate production has surpassed lactate elimination and correlates strongly with the poor metabolism of oxygen and hypoxia (Langley and Langley, 2012).

A lactate level of greater than 2 mmol/L would indicate that a patient was suffering from severe sepsis, while a level of 4 mmol/L or greater despite fluid therapy would be classed as septic shock (Robson et al, 2009).

When symptoms are prolonged for 24 hours the mortality rate can be as high as 89% (Nguyen et al, 2004). Many patients present to the ambulance service having had infections for prolonged periods and thus many would have a raised level of lactate.

Early lactate clearance in septic shock via fluid resuscitation and antibiotics is associated with improved morbidity and mortality (Nguyen et al, 2004). However, hyperlactataemia first needs to be suspected and identified.

Blood lactate is a sensitive marker when evaluating the seriousness of a patient's condition and is a recognised marker of tissue hypoxia (Bakker and Jansen, 2007. Traditional monitoring that takes place in the ambulance, such as pulse rate and blood pressure, often do not change until a patient has become critically ill (Jansen et al, 2008), but many of these patients may have a raised lactate.

A lactate reading of greater than 2mmol/l reflects mortality and morbidity better than pulse rate and blood pressure (Bakker and Jansen, 2007). This means that a lactate reading can be used to arrive at a diagnosis and subsequent treatment plan (Seymour et al, 2011). Indeed, taking a lactate reading is advised by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (Shapiro et al, 2010) and is an important part of the sepsis six care bundle, the adherence of which is associated with a 34% reduction in mortality (Daniels et al, 2011).

If ambulance clinicians could take a lactate reading it would help promote better recognition of sepsis and lead to a reduction in time to implementation of sepsis six, which would improve patient outcome.

Hand-held machines have now made it possible to monitor lactate both quickly and easily (Kruse et al, 2011). Some countries are ahead of the UK in using lactate monitors in the pre-hospital setting. A study carried out in the United States has recommended the use of such monitors to facilitate the early recognition and management of sepsis (Robson et al, 2009).

Extending lactate monitoring to the pre-hospital environment also provides opportunities to drive forward care to those suffering from a range of illnesses and medical conditions. For instance, lactate has been found to be prognostic of mortality in trauma patients (Manikis et al, 1995), overdoses of certain medications such as paracetamol (Bernal et al, 2002) and burns victims (Jeng et al, 2002), among others. In the same way a blood glucose reading can be indicative in various medical conditions, so too can a lactate reading be used to identify the severity of various illnesses, which may influence treatment and transport decisions.

There is a consensus that pre-hospital lactate monitoring needs to be part of a wider treatment regime (Pearse, 2009) such as administering antibiotics and fluid therapy. It is also envisaged that further training will be needed for pre-hospital clinicians.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to pre-hospital lactate monitoring that require consideration. In-hospital lactate monitoring would include arterial measurement, which would better reflect hypoperfusion and hypoxia (Seymour et al, 2011). Pre-hospital monitoring would be limited to pointof-care (POC) measurement using a small amount of fingertip blood on a test strip. Some evidence suggests this may cause variances in results but others clearly state that POC measurement correlates accurately with laboratory results (Gaieski et al, 2011). Reliability is thus ensured.

The use of a single lactate reading has limitations and serial measurements are more reflective of serious illness and mortality (Nguyen et al, 2004).

Serial measurements would be used to support lactate clearance in the in-hospital environment and could be used to measure the response to treatment initiated in the pre-hospital setting (Jansen et al, 2008). However, there is undeniable evidence that correlates raised pre-hospital venous lactate and in hospital mortality (Pearse, 2009).

A further limitation of implementing routine lactate monitoring is the financial cost of the POC monitors which have been estimated to cost up to £400 each (Small, 2012). At a time when the NHS is required to save 4% of its budget and is in the midst of ‘tough financial times’ (NHS Confederation, 2013), this may be deemed too expensive and may halt any momentum to drive sepsis care forward. It may also explain why monitoring is not already routine (Seymour et al, 2011).

However, the cost to treat each sepsis patient is between $22 000–$50 000 (Seymour et al, 2010). This represents a vast financial cost to healthcare systems around the world, and is far more than the costs required to equip the ambulance service with lactate monitors. If monitors were available in the pre-hospital setting it would provide the opportunity for early detection of patients with sepsis and may prevent admissions to intensive care units, thus significantly reducing costs.

One UK ambulance service has recently trialled blood lactate monitoring as part of their sepsis management pathway, and they have witnessed an increase in the number of patients diagnosed as septic.

However, this rise cannot be solely attributed to measuring blood lactate because it was coupled with additional sepsis awareness and training. The service has no statistics on the prognostic value of lactate readings alone. They reported a problem with the equipment being affected by extremes of temperature and costs of consumables such as the monitor test strips.

Exclusions

It is important to note that this paper is recommending the monitoring of lactate for adults aged 18 years and over only. Patients under the age of 18 years would not be monitored primarily because of the epidemiology of sepsis in children and adults.

Sepsis affects multiple body systems, resulting in organ dysfunction with alterations in blood pressure, pulse rate, respiratory function etc.(Wheeler et al, 2011).

As these systems and organs function differently in children the affect and outcome of sepsis is significantly different, as is the effect of lactate (Watson and Carcillo, 2005). A much greater understanding of these differences and how they affect sepsis is required (Wheeler et al, 2011). With this in mind, it would be inappropriate and unethical to apply pre-hospital lactate monitoring to children based on evidence applied to adult sepsis management.

Conclusions

Lactate is a sensitive marker of sepsis and correlates strongly with mortality. A raised lactate can also be prognostic of mortality in a range of other conditions. Lactate can be monitored in the prehospital setting without complication and with reliable accuracy. An early lactate reading can promote better recognition of sepsis and can lead to a reduction in time to implementation of sepsis six, which would improve patient outcome.

Evidence from a range of clinicians and experts agree that routine lactate monitoring for sepsis management can be achieved and should be rolled out across the pre-hospital setting, although further trials of equipment are needed as is training for paramedics.

Conflict of interest: none declared