The aim of this exploratory study was to gain an understanding of the current knowledge base and clinical practice of UK paramedics in relation to the clinical skill of cardiac auscultation (CA). The primary areas of interest were to explore the current frequency of CA undertaken by UK paramedics, and paramedic exposure to abnormal heart sounds in clinical practice.

Free-text responses were invited to allow respondents to voice other concerns and opinions regarding the skill of CA. This study provides original knowledge in the area of pre-hospital patient assessment and highlights the variability in current practice. It also provides an insight into the perceived barriers and restraints involved in pre-hospital CA and advanced patient assessment more widely.

Background

CA is a skill using both the bell and diaphragm of a stethoscope on the praecordium to identify both normal and abnormal sounds emanating from the heart. This is part of a complete examination of the cardiac system and is often performed after examining the patient for other signs of cardiac disease, and inspecting and palpating the praecordium. Most commonly, auscultation is performed over the four valve locations (Table 1). The patient may be asked to move position, commonly to lean forward or roll onto their left side, or to hold their breath. Findings may include the normal heart sounds of S1 and S2, splitting of these sounds, a third heart sound (S3), a fourth heart sound (S4), murmurs caused by turbulent blood flow, or extra sounds such as clicks, plops and rubs. A cardiac examination is then completed with examination of the lung bases, abdomen and legs for peripheral oedema and vascular disease.

| Valve area | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aortic | Pulmonary | Tricuspid | Mitral | |

| Anatomic location | 2nd intercostal space, right sternal border | 2nd intercostal space, left sternal border | 5th intercostal space, left sternal border | 5th intercostal space, midaxillary lined |

Despite recent advances in ultrasound technology and bedside echocardiography, CA is still a core skill in clinical medicine and may identify serious pathologies not previously diagnosed (Hellaby, 2013). Furthermore, until handheld ultrasound devices are available to all paramedics, CA is likely to continue to be one of the only ways of evaluating cardiac valve disease in the out-of-hospital setting.

While significant work has been done to investigate ways to enable auscultation in the often noisy pre-hospital environment, there is a paucity of evidence relating to the clinical use and accuracy of CA when undertaken by paramedics (Mallinson, 2010)—there are some exploratory data indicating that around 40% of UK paramedics are unable to correctly identify standard locations for CA (Mallinson, 2017). Despite this dearth of evidence, CA is still a component of a paramedic's detailed cardiovascular examination, and is taught on paramedic courses and included in core paramedic texts (Gregory and Mursell, 2015; Willis and Dalrymple, 2015; Blaber and Harris, 2016; College of Paramedics, 2016). With this limited evidence, it would be difficult to predict the extent to which UK paramedics are practising the skill of CA and how accurate such an assessment would be. The current study provides an initial insight into this facet of paramedic practice, laying the groundwork for further studies to answer such questions.

Methodology

The present study was assessed against the NHS Health Research Authority Guidance document and found to be exempt from the need to gain formal ethical approval. This study does not involve patients or use an experimental design leading to a change in current practice (NHS Health Research Authority, 2012). Participants voluntarily completed the online survey and no questions required a mandatory response. The survey was anonymous, with the option of providing a contact email address to receive an information leaflet about CA and a certificate as evidence of their involvement in the research project.

This is an exploratory study and, as such, was designed with a small sample size in mind. Ideally a sample of equal to or greater than 378 would have allowed interpretation of results with a confidence interval of 95% with a 5% margin of error. Such a sample size would then have allowed for a degree of generalisation to the whole UK population of paramedics, in light of the research findings. This is in relation to the total number of paramedics registered in the UK which, at the start of the study period (30 consecutive days commencing on 24 July 2016), was 22 626 (Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC), 2016).

Sampling was undertaken over 1 month by posting a link to the online GoogleForms survey on the following social media platforms: Twitter, Facebook, and Reddit. Both convenience and snowball sampling were used over a month-long recruitment. A sample size of 328 was achieved, which was close to the preferred size and was considered acceptable for this exploratory study.

The survey tool asked about participants' current role and place of work. It also included Likert scales (ranging from 1 (Not at all confident) to 5 (Very confident), for the participant to undertake a self-assessment of their confidence in recognising normal and abnormal heart sounds, as well as a list of abnormal heart sounds, allowing participants to select those they had heard in clinical practice. There was also space for free-text responses to allow respondents to voice any other opinions on the topic.

Limitations

The current study is exploratory in nature and does not aim to produce conclusive results representative of the UK paramedic population. The survey methodology was selected as a means of limiting the time and resources expended on research of a relatively under-investigated area of pre-hospital care. No funding support was gained for the study, meaning financial considerations were paramount.

The use of an online survey, while a useful medium for gaining responses rapidly, is prone to bias. Specifically, selection bias is a concern. It is likely that those paramedics who responded to this survey are active online and visit pages related to paramedic practice and pre-hospital care. This may exclude a proportion of the UK paramedic population, and it is difficult to quantify numbers excluded in this way. It could also be the case that those who responded were more, or less, likely to use CA in their practice than those who did not respond; again, it is impossible to quantify this. Furthermore, as this survey asks about perceived competence, it is difficult to know how this translates into actual competence in practice. While it has been recognised that self-reported and objectively measured competence vary (Katowa-Mukwato and Banda, 2016), this is difficult to eliminate with a survey methodology.

Producing a survey that was quick to complete also led to the omission of detailed questions about respondents' personal and educational background. In future, to produce generalisable results with a high level of validity, questions would need to be included covering respondents' age, gender, educational route, practice settings (past and present) and the amount of formal and information training received in the area of CA.

Results

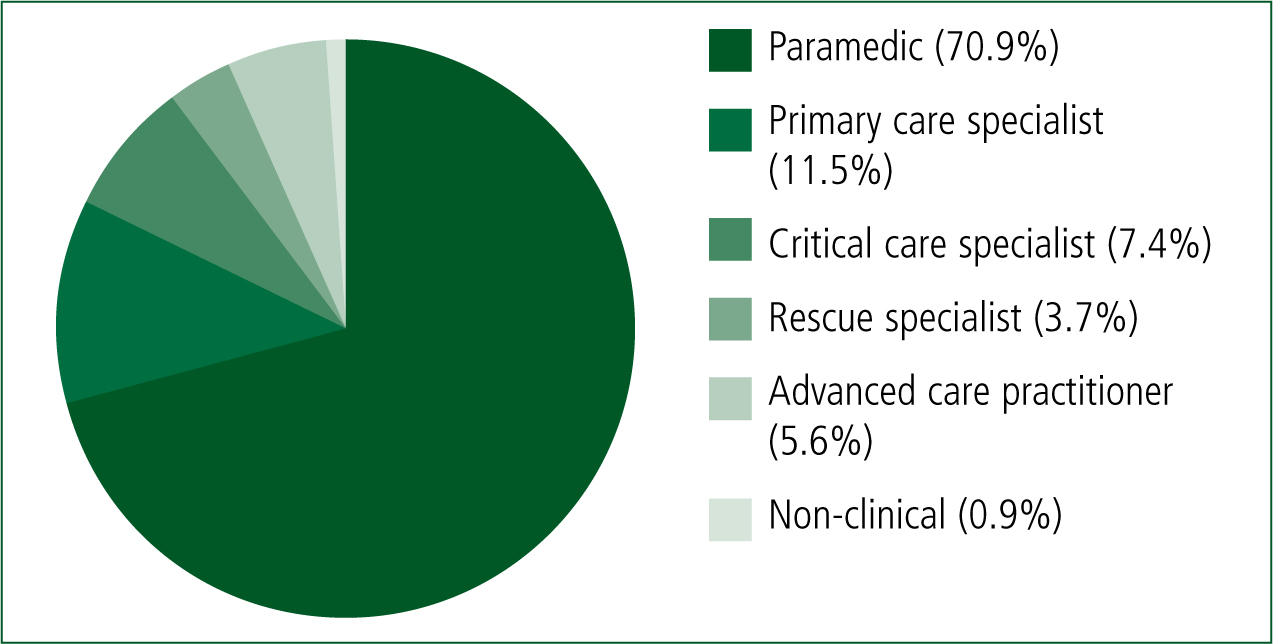

In total, 328 surveys were completed, with a number of participants choosing not to answer some questions. In total, 323 participants described their current role (Figure 1). This revealed that the majority of respondents self-identified as paramedics (n=229), with the next largest proportion identifying as primary care specialists or emergency care practitioners (n=37). There were 320 respondents who identified their main place of work; 297 of these identified as working in the pre-hospital environment, with a small number working mainly in primary (n=13) or secondary care (n=10).

In relation to how often the respondents on average undertake CA, out of the 321 responses, around half said they use this skill rarely (n=161; 50.2%), with just over a quarter undertaking the skill during most shifts (n=83; 25.9%), and only one eighth of respondents undertaking CA every shift (n=40; 12.5%). Notably, just over one in ten participants (n=37; 11.5%) stated that CA was a skill which they never undertook in clinical practice.

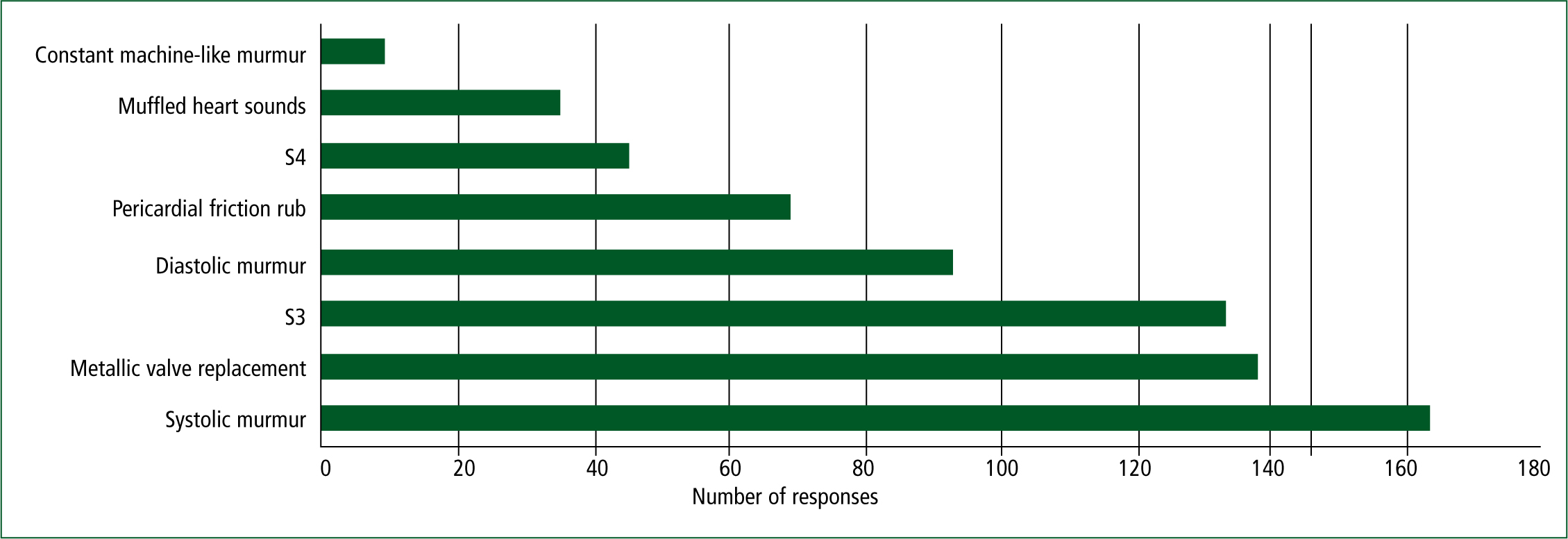

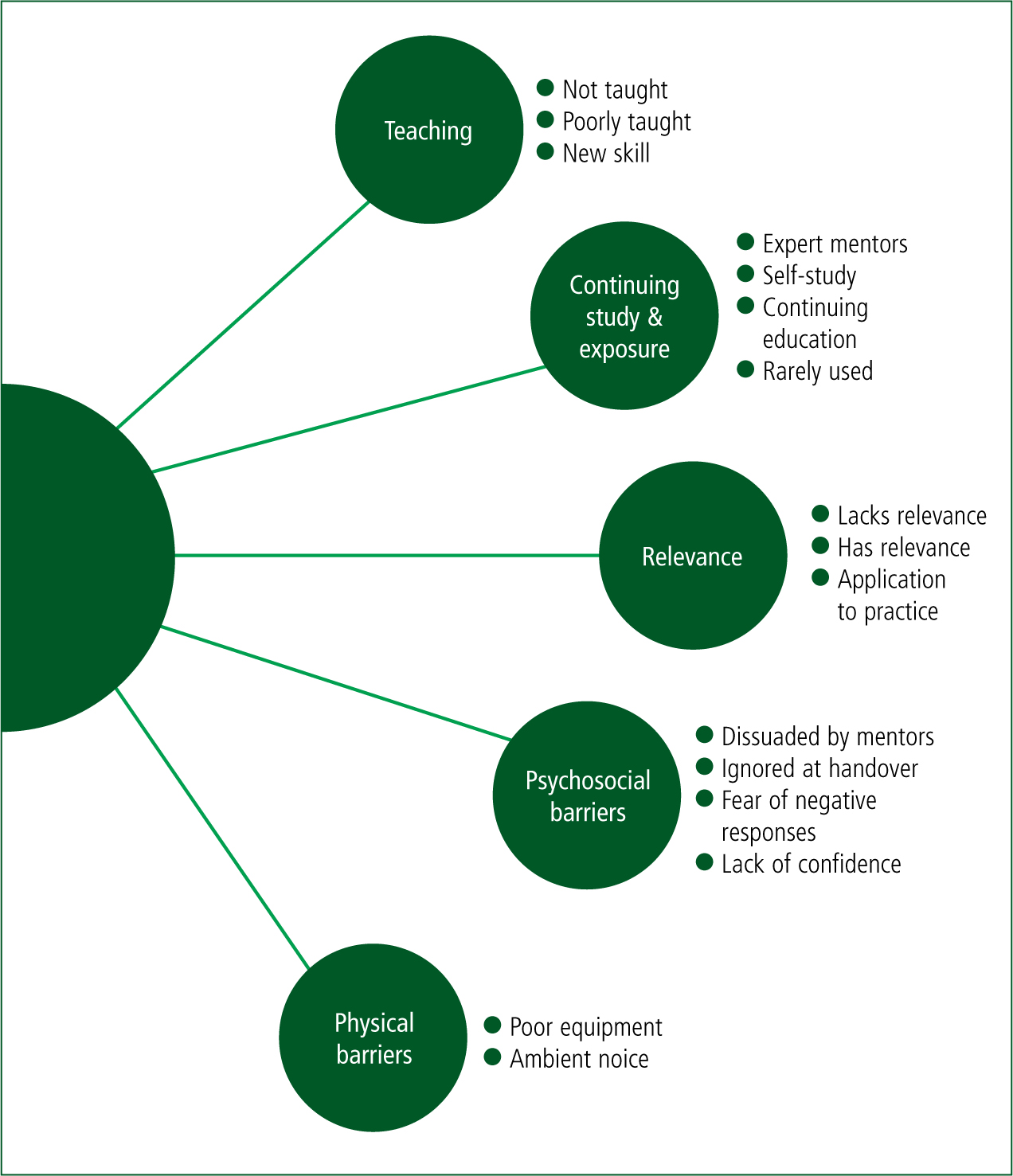

The paramedics' self-reported confidence in recognising normal heart sounds revealed a skewed distribution towards high confidence. However, the self-reported confidence in recognising abnormal heart sounds revealed a distribution slightly skewed towards low confidence. When asked which heart sounds paramedics had heard in clinical practice, the most commonly heard sound was a systolic murmur (n=163), followed by the sound of a mechanical heart valve (n=138), and a third heart sound (n=133). The full responses to this question are shown in Figure 2 and Table 2. There were 50 free-text responses provided by participants, representing 15% of total respondents. Initial coding of free-text responses identified sixteen themes. The main themes were then amalgamated into broader categories of interlinked or related topics. This resulted in five major categories (Figure 3):

| Number of responses | Percentage of respondents | |

|---|---|---|

| Third heart sound | 133 | 50.8% |

| Fourth heart sound | 45 | 17.2% |

| Systolic murmur | 163 | 62.2% |

| Diastolic murmur | 93 | 35.5% |

| Constant machinery murmur of patent ductus arteriosus | 9 | 3.4% |

| Pericardial friction rub | 69 | 26.3% |

| Muffled heart sounds resulting from cardiac tamponade | 35 | 13.4% |

| Metallic valve replacement | 138 | 52.7% |

Discussion

These results demonstrate a fairly low frequency of application of CA in current UK paramedic clinical practice. Interestingly, it also highlighted that one in ten respondents never undertook CA. This number is relatively high, and is not fully accounted for by respondents stating they worked in a non-clinical role. This suggests that some paramedics assessing patients in primary or secondary care, or indeed seeing undifferentiated patients in the pre-hospital setting, are never using the skill of CA.

When relating these data to the self-reported confidence in recognising both normal and abnormal heart sounds, it could be postulated that paramedics are not undertaking the skill as they lack confidence in their abilities. This self-reported lack of confidence could be the result of a number of factors.

It could be hypothesised that some of these paramedics were never taught CA as a clinical skill, while others may have been taught this skill but subsequently have not had enough opportunities for continuing development and learning in this area, leading to subsequent skill fade. While it is appropriate to not undertake a clinical procedure in which you are no longer competent, it is likely that CA would be expected of a practising UK paramedic. Practising paramedics should therefore aim to maintain competence rather than ceasing to perform this skill.

When respondents were asked which abnormal heart sounds they had heard in clinical practice, there was an interesting range of responses (Figure 2). The high frequency associated with a third heart sound and a systolic murmur may be a result of these sounds being specifically listened for during pre-hospital cardiac examination. The third heart sound has been recognised to be associated with heart failure (Mehta and Khan, 2004); paramedics may be using the presence of this sound therefore to assist in their diagnosis of acute heart failure and resultant pulmonary oedema before initiating treatment with nitrates and diuretics. Equally, a systolic murmur may be a sign of aortic stenosis (Hellaby, 2013), the presence of which may lead a paramedic to consider withholding therapy with nitrates.

A large proportion of respondents also reported hearing the noise of a metallic valve replacement. It is likely that this sound has such a high exposure rate as it is very easy to detect and has a clear past medical history to lead to its discovery. It is unknown however if paramedics would use the presence of a metallic heart valve to alter their management plans. Sixty nine respondents to this question had heard a pericardial friction rub, which is a common sequela in patients experiencing acute myocardial infarction (MI) (Dubois et al, 1985) and some weeks after MI in Dressler's Syndrome (Dressler, 1956; 1959), as well as in pericarditis from any cause (Mootham, 2017).

Analysis of free-text responses

The free-text responses provided insight into some of the reasons behind the low levels of confidence and usage of CA during patient assessment.

Teaching

‘I am a university educated paramedic who did a 2 year foundation degree and we didn't talk once about cardiac auscultation.’

Limitations in teaching and ongoing exposure were brought up in a number of free-text responses (Figure 3). These responses identified a perceived lack of high-quality education provision at an undergraduate level in the clinical skill of CA, in both the higher education setting and in the practice environment. A number of respondents also named UK universities where they completed that paramedic training which did not teach CA. Previous research has highlighted poor performance at the skill of pulmonary auscultation in undergraduate paramedic students, suggesting a greater emphasis may be needed on auscultatory skills in undergraduate curricula (Williams et al, 2009).

Continuing study and exposure

‘The knowledge fades without using [the] skill regularly.’

A number of respondents highlighted the lack of high-quality ongoing mentoring from senior clinicians. Some clearly highlighted that ‘expert mentors would make me more confident in employing this skill’ and that they ‘learnt because [they] work with more experienced clinicians’. This emphasised that this could be a problem for the majority of frontline paramedics, who only infrequently work with a more senior clinician who is able to mentor them in relation to undertaking clinical skills. While some groups of paramedics may routinely work alongside doctors, advanced paramedics, nurse practitioners or other senior allied health professionals, this is far from the norm.

The findings from this analysis provide evidence of a need to develop a more substantial programme for mentoring and support for paramedics throughout their career, to facilitate their own learning and development, and while the newly qualified paramedic (NQP) role may assist in a small way, it does not provide a structure for life-long learning and mentoring.

Relevance

‘Not that relevant to pre-hospital paramedic practice.’

The issue of relevance was emphasised in the qualitative analysis of responses. Currently, there is sparse evidence for many interventions and diagnostic procedures undertaken in the pre-hospital setting; this is also true for patient assessment skills used by paramedics. Therefore, it is understandable that many paramedics striving to undertake evidence-based practice may question the use of CA to their practice.

Furthermore, practitioners from a critical care background highlighted that they believed CA was unlikely to add to their assessment and management of their patient group, who have predominantly suffered major trauma. While this is likely to be true for patients with traumatic injuries during the pre-hospital phase, once such patients are stabilised and require secondary or tertiary transfer under the care of a critical care paramedic, CA may indeed prove a useful and informative skill.

Psychological barriers

‘A lot of paras lack confidence, afraid of being wrong or like they're being flash in reporting their findings'

A number of psychological and social barriers were also put forward by respondents (Figure 3). One of these was the issue of feeling dissuaded by mentors when attempting to undertake CA. One paramedic related how they have ‘taught cardiac auscultation to undergraduate paramedics then their mentors have told them they don't need it as they [the mentors] are not confident to do it themselves.’ Fear of negative responses from peers was highlighted as a related issue, and one response stated that ‘I'm the only paramedic I know who does it’—highlighting that CA may be a culturally undesirable activity in some organisations.

Responses also reflected a concern that findings from CA were often ignored at handover and therefore would not benefit the patients' ongoing care. One respondent stated that ‘hospital rarely listen to handover about advanced cardiac assessment’ and another that it ‘doesn't help that it's often ignored or dismissed on handover which [is] off putting.’ This may be a well-founded concern as a lack of evidence surrounding the handover of information from pre-hospital to hospital staff has previously been identified, and that this is an area where poor communication can have serious negative consequences (Wood et al, 2013).

Physical barriers

‘Have you tried listening to anything in an ambulance with dual carriageway traffic driving past?’

In terms of physical barriers, poor equipment and ambient noise were highlighted by a number of respondents (Figure 3). Difficulty in auscultating for heart sounds in the often noisy pre-hospital environment was cited as a major barrier to clinical practice by four respondents. This is in keeping with past works, which have questioned the ability to adequately auscultate in the pre-hospital arena (Brown et al, 1997) or with any substantial background noise (Groom, 1956). While the problem of environmental noise may in some cases be unavoidable, this is a barrier which can be addressed by the clinician in some situations. Timing auscultation to a moment when the patient is in the quietest environment, or asking for quiet at the scene of an incident may prove beneficial. Technological solutions such as electronic stethoscopes could also be used, as these have been demonstrated to aid CA in the pre-hospital setting (Tourtier et al, 2011; Fontaine et al, 2014).

A related barrier is the perceived provision of inadequate equipment by the employer, with one respondent clearly stating that ‘standard issue stethoscopes [are] poor for CA.’ This assertion is supported by studies which have demonstrated that more expensive stethoscopes allow for better identification of abnormal sounds on auscultation, when compared with low-end stethoscope models (Mehmood et al, 2014). Stethoscopes have traditionally been the personal equipment of the clinician; however, it has increasingly been recognised that they may act as fomites, transmitting infections (Haun et al, 2016). In an effort to reduce nosocomial outbreaks, some critical care areas have adopted the practice of patients having personal stethoscopes which travel with them; UK ambulance services may need to adopt such a practice in the future.

There was also a strong dichotomy of opinion; there were paramedics who felt investigating paramedic CA was ‘academic snobbery’ and that even though they have ‘never trained in it [they] do not feel this has had a negative effect on patient care’ and those who believed CA ‘should be taught to, and expected of, every paramedic’, while others felt ‘this skill is relevant and deserves a more comprehensive coverage.’ With such a strong division among the profession, it is unclear how to move forward and, more importantly, whether CA is a skill required of the modern UK paramedic.

Conclusions

This was an exploratory study seeking to gain new insight into paramedic patient assessment skills within the population of UK paramedics. Results obtained allow for a better understanding of the current practices of UK paramedics in relation to CA, and suggest some barriers to this practice. While the area of paramedic patient assessment is vast, this study has highlighted a number of issues related specifically to the clinical skill of CA, as well as raised further questions about paramedic patient assessment in general.

The issue of relevance to practice was highlighted in this study, demonstrating the need for investigation across a broad area, involving current and future paramedic education and clinical practice. Further work needs to be undertaken to investigate whether pre-hospital CA has an effect on paramedic decision-making and patient outcomes. This could lead to further work exploring which clinical grade of UK paramedic should be expected to maintain proficiency in this skill. This could also inform similar investigations into the use of other clinical examination skills practised by paramedics, with the hope of directing paramedic education towards the clinical skills that most benefit patients.

Following on from this research, further study could be directed towards understanding the scope and importance of barriers to effective paramedic practice. A number of barriers were identified in the present study and it is hoped that this identification is the first step in overcoming such obstacles. Further research could also quantify current paramedic practices and knowledge in the area of patient assessment. Information gathered in this work could also be used to inform educational interventions addressing identified deficits.