Mindful of the current driver for parity of esteem between mental and physical health care (McShane, 2013), for those in mental health (MH) crisis, it is well-evidenced that first presentation will often be within the pre-hospital setting (Hawley et al, 2011). It has been recognised ‘that historically and currently, paramedics are the first point of contact for patients with mental health episodes’ (Berry, 2014). In the UK, the London Ambulance Service (2015) stated that they had experienced a 15% increase in MH-related calls between 2012 and 2015. A report published by the UK National Audit Office identified that ambulance service demand is rapidly increasing and MH-related conditions are perceived to be a contributing factor (Morse, 2017).

Following a membership survey conducted by the College of Paramedics, paramedic clinicians within the UK have stated that they feel they have inadequate skills and knowledge to be able to provide sufficient care to patients with MH conditions (Berry, 2014). Recommendations following the Paramedic Evidence Based Education Project (Lovegrove, 2013) suggest a stronger knowledge and skills focus during training in a number of areas, including general MH, wellbeing and dementia.

Not only is it acknowledged that there is a requirement for more MH training for student paramedics, but it is also well-documented that the ongoing wellbeing of qualified paramedics is an area which needs to be recognised and formally addressed. Owing to the nature of the work that emergency service healthcare providers are subjected to, it has been identified that such staff, including paramedics, are at an increased risk of experiencing stress and other MH conditions (Deady et al, 2017). This, together with the increasing service demands generally on the paramedic services, therefore suggests that stress among paramedics and risk to their MH and wellbeing are likely to increase.

Action research

Action research is commonly described as any research into practice carried out by those involved in that practice, with an aim to change and improve it. It is concerned therefore with both ‘action’ and ‘research’, and the links between the two. Indeed, the unique combination of the two is what distinguishes action research from other forms of enquiry. Crucially, action research is ‘research in action rather than research about action’ (Coghlan and Brannick, 2010).

The current article describes an action research model considered as a process of enquiry into the effectiveness of MH specialty placements for first-year paramedic students on the Bournemouth University (BU) BSc (Hons) Paramedic Science Programme in 2016, with a focus on changes implemented and their subsequent impacts.

The BU University Practice Learning Adviser (UPLA) team is a small group of clinically and educationally qualified individuals (e.g. registered nurses and paramedics who are also mentors and education tutors directly employed by the university), who take responsibility to quality-assure those practice placements supporting BU health and social care students. They do so using an established menu of jointly agreed (with practice partners and professional bodies) quality assurance mechanisms, and through close working relationships with placement practice education teams (in both the NHS and the private sector), as well as with on-site mentors. The authors of the current paper are two members of the UPLA team—the second author (MJ), who is a qualified paramedic, and the lead author (EJ) who is a dual qualified mental health/adult nurse.

This serves to increase the likelihood of a positive placement experience for both students and practice partners. An important facet of these joint quality assurance processes is to regularly review student feedback, the resultant discussions seeking to develop and enhance the learning environments. Contemporary student feedback is always available as BU students are required to evaluate each individual placement via an online questionnaire, as well as reporting through the formal BU Concerns Protocol (Bournemouth University, 2016).

As part of these review processes, it was noted upon placement evaluation that a pattern emerged. There was a lack of consistency in learning experiences for the pre-registration paramedic students when undertaking their placement. Students either described that they had experienced meaningful learning and insight into this specialty, or that they had learned very little.

This feedback was not related to any one placement at any one time. Indeed, qualitative comments reflected the limited opportunities available for learning given the high clinical pressures often within placement settings and the presence of other pre-registration students and/or availability of learning support staff (e.g. mentors or associate mentors). Students also suggested that they felt ill-prepared prior to the MH placement regarding what they could expect. This was not limited to learning opportunities but also included anxiety around an unfamiliar setting and concern commonly identified as ‘what not to say’ to patients.

This evaluation information was triangulated with feedback from key stakeholders, i.e. paramedic practice partners, service users, two members of the UPLA team and the paramedic academic programme team. At this point in the process, the evaluation reviews sought to examine whether a change was required, or whether an intervention was necessary to improve the placement experience. This could be achieved through a systematic review of the evidence and collaborative reflection (Cohen et al, 2011) to identify and focus on a commonly agreed goal.

Given that this was not, at this point, a formal research study, there was no requirement to seek full and formal ethical approval. All the information available and discussed was routinely available via the BU quality assurance processes for teaching and placement feedback. The scoping material was obtained with verbal consent, including consents in sharing information for publication and evaluation purposes.

The reflection cycle

The emerging findings from the reflection cycle suggested a key opportunity for change, with collaboratively agreed objectives. These include:

Planning

Collaborative consensus from the key stakeholders was that a new approach offering and supporting a paramedic MH placement was required. It was agreed that rather than the students going ‘out’ to a placement, the placement would be brought ‘in’ to them in the university setting. Following successful partnership working with the Dorset Mental Health Forum (a local peer-led charity promoting wellbeing and recovery) in jointly delivering MH education to pre-registration nursing students, it was decided that building on this partnership would be appropriate given its unique strengths including peer/service user facilitation of learning rather than being academically led. It is of note that the previous collaborative educational work was focused on academic endeavour. This partnership sought to meet the requirements of a quality-assured practice placement, and therefore also required to meet the professional degree requirements of assessment.

The two key members of the UPLA team were keen to maintain the essence of action research collaboration by including participants—in this case, the paramedic students themselves.

Therefore a ‘co-produced placement model’ was explored and agreed upon to meaningfully include all key stakeholders. As such, two formal ‘development days’ were planned with all key stakeholders including the two UPLAs and the paramedic academic programme team as representatives from BU, members of the Dorset Mental Health Forum (including peer-support workers and the service users, skilled facilitators of learning as well as qualified health and social care professionals), two second-year paramedic students, paramedic mentors, and education leads from paramedic practice partners.

Issues discussed at these meetings included the initial costings and key placement requirements. The latter pertained to ensuring that this bespoke placement still provided students with the opportunity to achieve the practice skills and competencies already identified in their practice assessment documentation: Ongoing Skills Achievement Record. This is a formal record of skills, knowledge and behaviours achieved in the placement environment and endorsed by suitably qualified paramedics, achieving parity of placement opportunity with previous cohorts. This would align with the skills identified for an undergraduate-degree programme.

Key to these discussions was ensuring that stakeholders understood that although the placement was being delivered in an academic environment, the focus was to be on professional practice and skills, not academia or theory.

Uniquely, the students would retain placement contact with service users throughout this placement, as service users were involved in the co-delivery and facilitation of learning (which included the sharing of service-user narratives), as well as being part of the assessment processes, e.g. feedback on performance in role-plays and values conveyed by students linked to the ‘6 Cs’ (Nevins et al, 2016). Essential to the effective co-production was the acknowledgement that all stakeholders had equal and valuable input and the process, from inception to delivery, was as important as the outcome and outputs.

Placement aims and goals

As a result of the two successful development days, it was jointly agreed that a consecutive 5-day MH placement at BU was to take place. Agreed essential elements for inclusion were the following:

On placement

Mindful of these aims, the resulting 5-day MH placement was set out in an agreed timetable for the week from 9 am until 5 pm. Aspects delivered as part of the timetable included:

All of the above were developed with practice partners and service users, with a focus on the role of the paramedic and making use of service user narratives, carer narratives, videos, group-work, role-play work, and actively exploring case scenarios.

Delivery was co-facilitated by all key stakeholders depending on their expertise, availability and educational experience. Students had to complete the workbook during each day, thus building a portfolio of evidence to share at the end of the placement and with future placement mentors.

Prior to delivery of the bespoke placement, information for the affected students (n = 30, the first-year cohort) was disseminated through both the paramedic programme team and also the two second-year students who developed their own information ‘poster’ to support their informal conversations with students. Opportunities were made available for students to ask questions and raise any concerns before the placement started in the academic summer term of May 2016.

Observations

All stakeholders agreed that feedback would be sought from students, facilitators, peer-support workers and mentors at the end of each day as an iterative process to inform and make any responsive amendments necessary for the next day.

As per action research, qualitative rather than quantitative data were sought with the emphasis on language rather than numbers, on critical reflection on both the process and the outcomes throughout. Therefore, feedback was sought from students digitally with responses collated on a large screen displayed ‘wordcloud’ (an online platform evaluation tool which immediately evidences and displays graphical representations of word frequency as offered by participants) at the end of each day, and then collated alongside daily facilitator debrief comments. The students also offered free comments on Post-it notes as to what they felt they had learned that day. No changes were required to next-day placement delivery following any of this immediate feedback.

As part of this feedback process, students were informed each day that their feedback would also be used to assist evaluation and possibly be used to inform publication and dissemination. As such, they could choose not to offer feedback or to withdraw comments at any time, both during and after the placement. Contact details for both the UPLA team members were made available for this purpose.

The daily feedback evidenced frequently occurring single words such as understanding, informative, empowering, insightful, emotional, enlightening, challenging, thought-provoking, inspirational, life-changing, team building, powerful and kindness. It could be suggested that the students experienced learning at a deep level, both personally and professionally.

Final student evaluation analysis

Student feedback was also sought at the end of the final day via an anonymous questionnaire. This included five broad questions about their experiences to replicate the standard expectation of placement feedback, and 27 out of 30 students responded. The students could tick a box on the form indicating their consent was not given to use their anonymous comments to develop further initiatives, or be used for publication and reassured that their comments were anonymous. A copy of the questionnaire can be found in Appendix 1.

Overwhelmingly, the feedback from students was more positive than had been anticipated. This was analysed thematically by a UPLA team member.

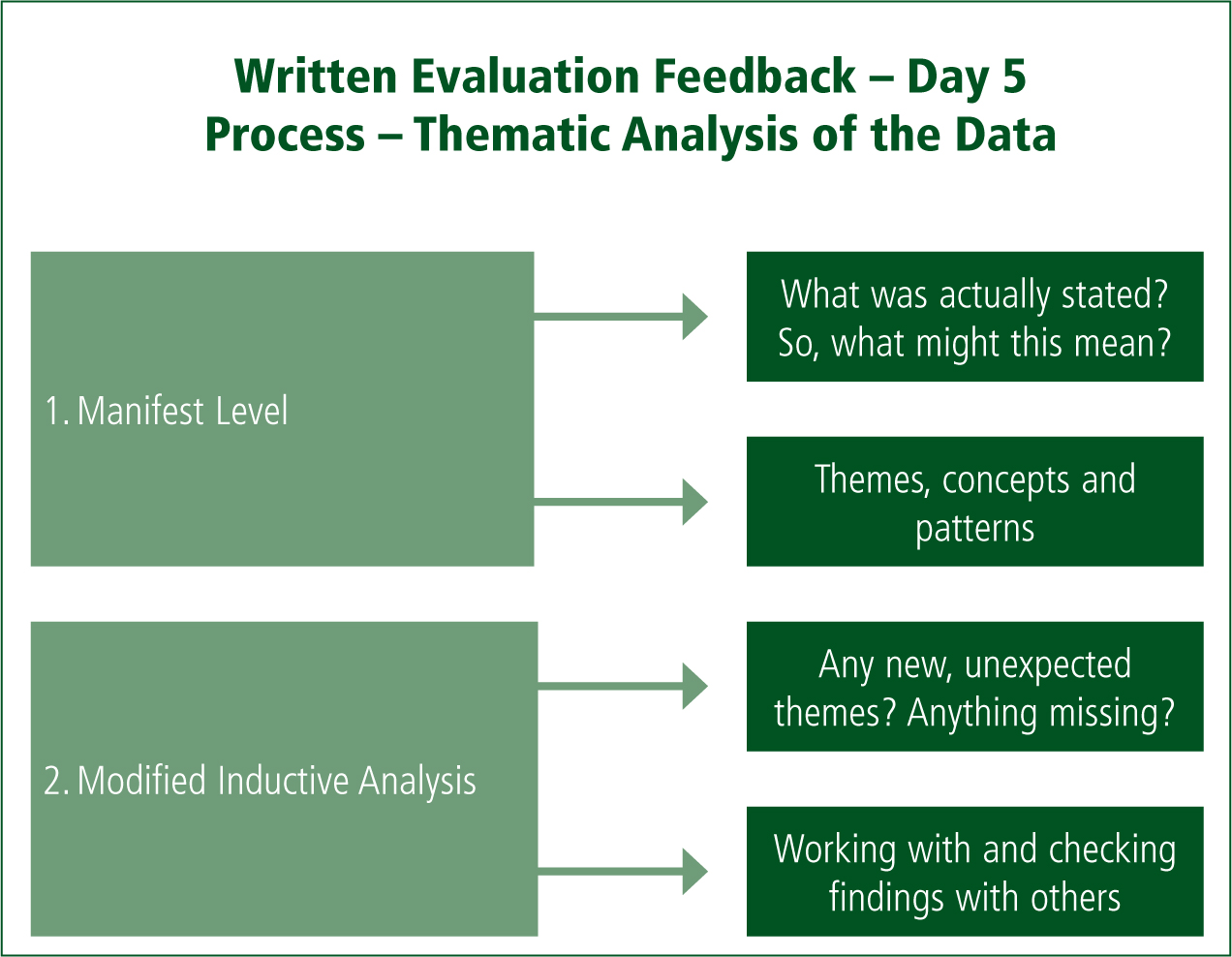

The manifest level (basic level of analysis with a descriptive account of the data, e.g. what was actually said, documented or observed with no assumptions made) of analysis began with all feedback available. This was followed by interpretative analysis (higher level of analysis concerned with what ‘may be meant by the response’, in the lead author's own words, and inferences and implications), whereby the data were read and re-read for an initial intuitive grasp of the emerging themes. The raw data were therefore organised into themes, concepts and patterns.

Modified inductive content analysis was also used where themes and constructs were derived with no former framework or counting—this is referred to as latent-level analysis. This process identifies and forms emerging categories. The approach was used because a UPLA team member wished to explore the rich data to search for any new themes that may have emerged, e.g. student group cohesion and sustainable impacts on practice (professional and personal). The process in its simplest form appears in Figure 1. True inductive content analysis would use absolutely no previous framework. However, the knowledge gained from co-production team during the scoping phase impacted on ‘knowing and knowledge’ (described by the lead author); therefore, the process could not be seen as inductive in its purest form.

Throughout the data analysis, themes emerged. A degree of immersion in the data was necessary for this process. A modified constant comparative strategy was therefore subsequently used. This analysis method (Table 1) focused on a process whereby categories emerged from the data via predominantly inductive reasoning rather than through coding from predetermined categories with the overall interpretation ‘confirmed’ lightly with the key BU team. Although not a purely ‘true’ constant comparative strategy, as is described within the grounded theory, the UPLA team used it as a means of addressing the quality issues.

| Preparation | Selecting a unit of analysis which may be a word or a theme (e.g. resilience, professional and personal skills, humanising care) |

| Organisation | Open coding, creating categories and abstraction. Notes and headings written in the text while reading it. Written material re-read, adding further headings to ensure capture of all content |

| Identifying emerging themes | Revisiting the data, codes and themes to elucidate emerging themes and ensure consistency |

Findings

Key impacts

Students identified significant key impacts that emerged strongly, including the following:

Emerging broad themes

The broader themes that emerged included:

Resilience

‘It's ok to ask for help.’

‘I now have the skills to help myself and others to maintain mental wellbeing.’

‘Personal wellbeing is paramount.’

Personal skills

‘The placement challenged my opinions.’

‘I have a clearer understanding of myself.’

‘I feel my confidence has grown.’

‘I am going to be more open-minded and accepting of people's problems and situations.’

Professional attitude

‘Seeing the person not the mental disorder because each and every mental health patient will react and have symptoms differently, treat each with respect and dignity.’

‘The individual, their emotions and the journey they may travel from diagnosis through to recovery so I will be more compassionate and understanding towards patients in crisis and their family/caregivers.’

‘The way to treat one patient may not be the way to treat someone else and look at patients as individuals including repeat callers.’

‘I feel like I have learned to validate, respect and care for people in their time of need, no matter the mental state; besides, you could be the only person they speak to that day and make the difference’

Development of professional skills

‘I have new communication skills in challenging situations related to mental health, building rapport, appropriate and safe questioning.’

‘Coping strategies for patients in practice and keeping clinically and professionally up to date.’

‘It is ok to ask difficult questions.’

‘Disseminating my knowledge to colleagues.’

‘How people can recover from bad situations—It should not be a hindrance to a “normal” life.’

Professional impact

‘Challenging stigma, understanding first-person perspective.’

‘If the repeat callers change their life, it is time well spent—look at patients as individuals including repeat callers.’

‘Paramedics can make a big difference.’

‘Take the lead in jobs involving mental health.’

‘By passing my knowledge on to other people who have to learn more about too, so I can try to improve the understanding of the public and the HCPC.’

‘I will try and educate patients and colleagues with what I have learned, and remain passionate about my ability to make a difference.’

‘Professionally I have learned the impact that the ambulance service can have upon someone's recovery and the influence we have.’

Evaluation follow-up

The students voluntarily took part in a short 30-minute focus group (all students, n = 30) at 6 months post placement, facilitated by the two UPLAs. The same broad evaluation questions were posed verbally, and responses were noted in writing and shared concurrently with the students in real time using a large ‘displayed on screen’ Word document.

Again, it was reiterated that students could choose not to comment and/or withdraw comments at any time by contacting either of the two UPLAs. Remarkably, the comments were similar—almost completely replicating the words and sentences, this time offering examples as to how they had implemented their new learning in to practice, e.g. ‘taking the lead in mental health calls’. This finding demonstrates that the impacts (including skills, behaviours and attitudes) were not only maintained over time but put into practical use. Interestingly, there was more explicit verbal evidence of having listened to the mentors' narratives pertaining to traumatic experiences while working. This enabled students to recognise their own need for support and how to formally access help through the avenues identified by the qualified paramedics.

Stakeholder feedback

An unexpected outcome from the daily and final-day feedback from all stakeholders was the ongoing knowledge and skills gained, and subsequently implemented, by the paramedics (practice mentors).

All mentors shared their learning, from the discrete, e.g. Considerations of the Mental Health Act (2007) and Mental Capacity Act (2007), to recovery focus philosophy and approaches, enhanced communication skills, development of skills for the facilitation of learning and teaching of students, experience in co-production, changes in how they practice pertaining to MH patients, e.g. recognising the need to listen and the importance of their input at a time of crisis and distress including verbal and non-verbal communication.

Conclusion

The feedback and evaluation data demonstrated that the innovation was successful in many ways. Indeed, it surpassed the initial expectations of the stakeholders given that all students passed with exemplary supporting comments. All students expressed having gained insight into the experience of patients presenting to paramedics with MH issues. They confirmed acquisition of relevant skills—both personally and professionally—to support such patients, as well as a reduction in anxiety when supporting them, as they will be increasingly required to do given the current health and social care environment in the UK for crisis intervention.

Arguably, because the placement allowed for ongoing practice and assessment of new skills, there was a reduction in the ubiquitous theory practice gap. The students expressed their initial wish to change the cultural approach of paramedics to MH call-outs and take the lead; they also did so at the follow-up and noted sharing their learning with peers and staff to begin this change process.