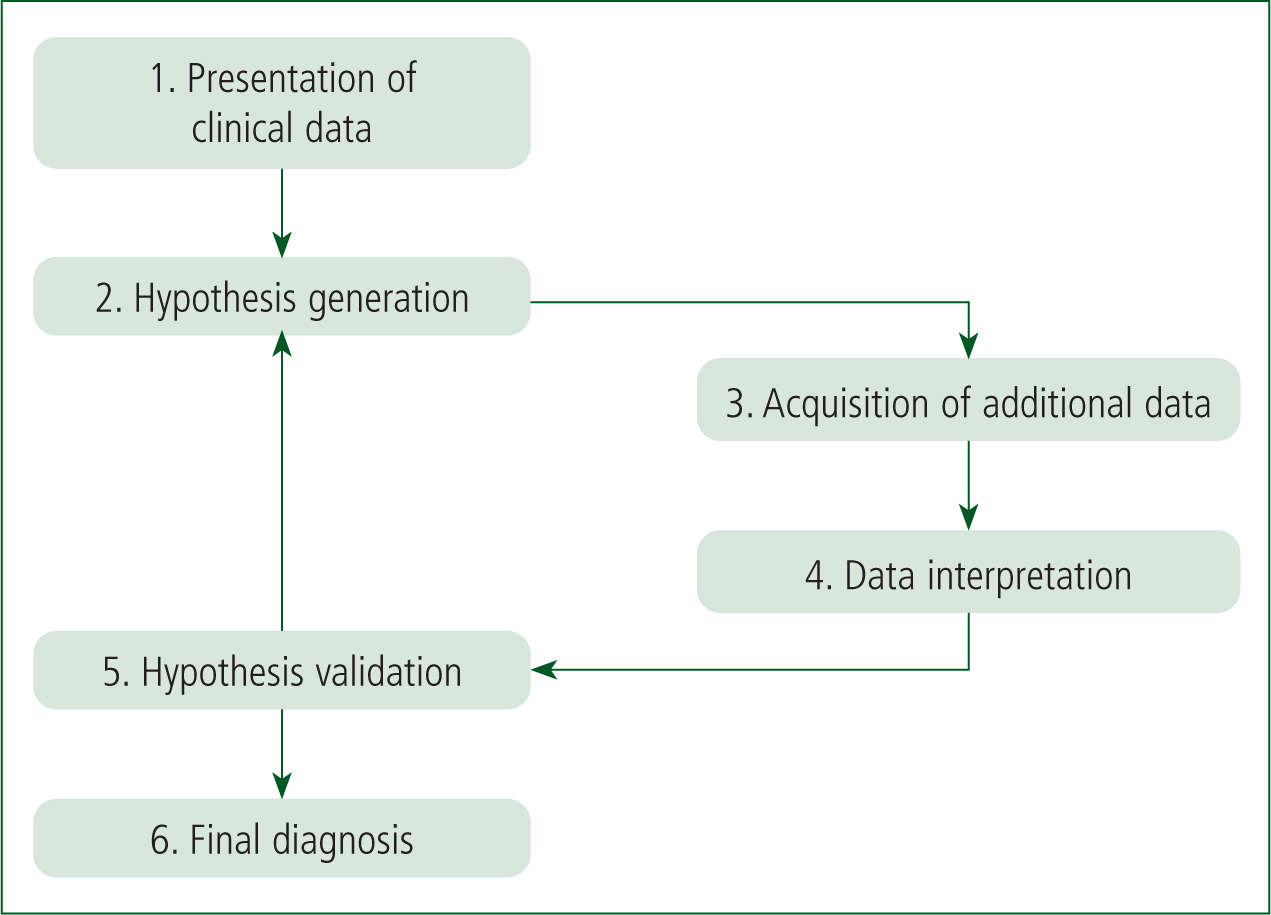

Clinical decision-making is a multifaceted construct, requiring the practitioner to gather, interpret and evaluate data in order to select and implement an evidence-based choice of action (Tiffen et al, 2014). In order to evaluate and critically explore this concept, use of the hypothetico-deductive model as advocated for by Elstein et al (1978) has been implemented throughout (Figure 1). Use of this framework may promote patient safety and can help to eliminate uncertainty leading to effective, and reasoned decision-making (Woodford, 2015).

Background

While in clinical practice during second-year placement, the lead author, a third-year student paramedic at the time of writing, attended a 49-year-old palliative care patient, Mr Smith, who was in the final hours of end-stage lung cancer, with his family and a nurse in attendance. Working under the supervision of a paramedic practice educator, a series of clinical, ethical and human factors were considered in the formation of a differential diagnosis and final decision in the care of this patient. Consent was obtained and all reasonable measures have been taken to ensure confidentiality, including the use of pseudonyms and omission of identifying factors (Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC), 2019).

Discussion

Prior to arrival, a brief descriptor on the mobile data terminal stated the patient's name, age and a single line of text: ‘difficulty in breathing’. These pre-encounter data are an important aspect of the cue acquisition phase within the hypothetico-deductive framework, as they prompt the paramedic to address significant situational indicators and promote effective information processing (O'Neill et al, 2004).

Conversely, and as was the case with regards to the initial treatment of Mr Smith, the pre-encounter data led to the formation of a confirmation bias (Collen, 2017). In this instance, the student paramedic placed greater emphasis on Mr Smith's dyspnoea, and less so on obtaining a comprehensive history from the family and nurse in attendance (Gregory and Mursell, 2010). Had a more objective approach been adopted at this early stage, the existence of Mr Smith's advance patient directive declining ‘life-sustaining treatment’ may have come to light sooner (NHS, 2019a). This is an example of anchoring, whereby new information is overlooked in place of a preconceived misconception originating from the pre-encounter data (Allen, 2019).

In an effort to mitigate such bias in future practice, the learner could be more mindful of considering external factors prior to and when first arriving on scene. In doing so, all forms of available knowledge are integrated to clinically determine the best course of action for the individual patient and are reflected as such through ‘clinical reasoning using inductive inference’ as outlined by Kyriacou (2008). Caroline et al (2014) support this suggesting that an analytical approach to information-gathering will inherently guide diagnostic reasoning and should be adopted in the presence of any uncertainty.

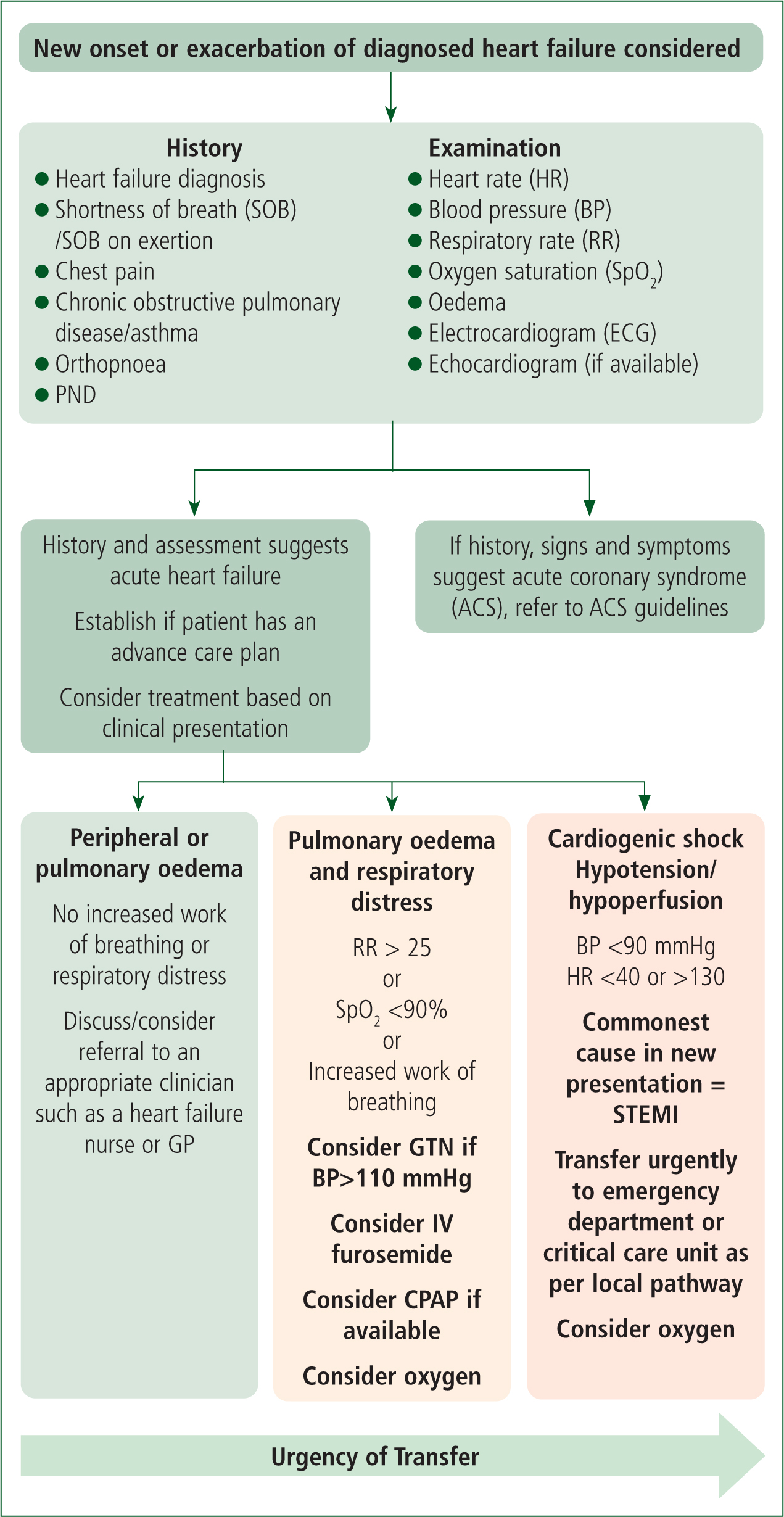

Following the information-gathering phase, a series of tentative hypotheses were formed (Elstein et al, 1978) to determine the acuity of the patient's dyspnoea and if he would in fact require ‘life-sustaining treatment’. On examination, course crackles were identified, leading to an initial hypothesis of pulmonary oedema secondary to acute heart failure (Purvey and Allen, 2017). Glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) is indicated as a treatment for this (Association of Ambulance Chief Executives (AACE), 2019) (Figure 2), and was repeatedly requested by the nurse, and subsequently the family in attendance. Upon further discussion with the practice educator, it was pointed out to the student paramedic that the patient would ‘likely only have hours to live’ as his condition had progressed into the final stages of end of life (Lim, 2016). The practice educator also suggested that the course crackles initially identified were likely terminal secretions that had formed as a result of the patient's inability to effectively clear his oropharynx as he had recognised from a previous clinical encounter (Lim, 2016).

The juxtaposition in contrasting levels of experience and understanding between the student paramedic and practice educator is evident here, and mirrored within Benner's intuitive, humanistic decision-making model (Benner, 2001). As a ‘novice’ with limited clinical experience, the student paramedic adopts a systematic and analytical approach in comprehending the causality of the patient's problem (Benner, 1984; 2001). However, the student paramedic does not account for the contextual elements relating to Mr Smith's palliative journey and disease trajectory, instead focusing solely on isolated clinical findings (Lord et al, 2019). By comparison, the ‘expert’ practice educator draws from significant clinical experience and intuition (Benner, 2001) in identifying additional hypotheses. This in turn highlighted the need for a transition from curative to palliative care (Lord et al, 2019). While Benner's model of clinical decision-making is a useful tool in exploring the unique characteristics and knowledge base embedded within the experienced practitioner (Stinson, 2017), it fails to acknowledge the significance of reflection and the impact that this can have on the decision-making process (Jasper, 2003). Moreover, and in consideration of how this may be applied to future practice, Coward (2018) outlines the importance of a reflective framework within clinical decision-making, affirming that expertise is developed not through experience alone, but rather experiential learning and reflection in practice (Caldwell and Grobbel, 2013). Such practice is also necessitated as a process of personal development (HCPC, 2019).

Having identified two tangible hypotheses, the final stages of the hypothetico-deductive framework ensue; cue interpretation and hypothesis evaluation whereby contributions, confirmation, or rejection of the original hypothesis occur (Elstein et al, 1978). When considering the practice educator's suggestion of terminal secretions as a probable cause of the patient's distressed presentation, there are a series of human factors at play (Collen, 2017; HCPC, 2019). It could arguably be a form of ‘satisficing’, whereby one hypothesis is accepted as it exceeds a personal subconscious threshold based on previous experience (Thompson and Dowding, 2009). This could potentially have been mirrored by the nurse's viewpoint that it was in fact significant pulmonary oedema, leading to her request that GTN be administered. To ensure the correct decision is reached in a safe and effective manner, it is vital that the health professional has an awareness of their own emotional frailties, particularly with regards to ‘humility over ego’ (Collen, 2017). When considering this requirement alongside the ‘Dunning-Kruger effect’, it is clear that the practice educator encompasses ‘true insight’, experience and humility in his approach (Dunning and Kruger, 1999). By encouraging the ‘novice’ student paramedic to take the clinical lead in forming a final decision regarding treatment, the practice educator is indirectly acknowledging that his own proposed hypothesis of terminal secretions could in fact be wrong and should be open to interpretation from others, regardless of clinical grade (Benner, 2001). In contrast, the nurse in attendance displayed ‘overconfidence’ in affirming the hypothesis of pulmonary oedema, and also demonstrated ‘illusory superiority’, a form of cognitive bias, in her refusal to engage with a student when rationalising her differential diagnosis (Dunning and Kruger, 1999). Familial needs and preferences are important considerations within the decision-making process and should be reflected as such in the care of the patient (to the degree that the patient wishes if indicated in an advance care plan) (NHS, 2019). From the initial history provided, the family highlighted that the patient was ‘drowning’ in what they believed were his own secretions. Upon review, and in consideration of Mr Smith's terminal prognosis, these were likely associated symptoms of end-stage lung cancer and not pulmonary oedema as had previously been discussed (Lim, 2016).

Ethical considerations

An ethical review relating to the four principles of biomedical ethics (Beauchamp and Childress, 2001) is paramount (HCPC, 2019), and will aid the paramedic in the final stages of clinical decision-making (Collen, 2017). When considering non-maleficence and beneficence (Beauchamp and Childress, 2001), an appreciation of Mr Smith's prognosis is essential, as GTN may only reduce preload on an already overworked heart, leading to bradycardia and potential asystole (Boyle, 2007). Although the patient's death is anticipated, an adverse drug event, such as this, would be directly harmful to the patient and may cause further distress to the family at an already difficult and emotional time (Lim, 2016). Conversely, if the administration of GTN did in fact alleviate Mr Smith's dyspnoea, any such benefit would be short-lived in effect and would arguably only prolong suffering (Braganza et al, 2017). Respect for autonomy (Beauchamp and Childress, 2001) must also be acknowledged in line with Mr Smith's fundamental and lawful right to self-governance (Human Rights Act 1998). The existence of an advance directive declining ‘life-sustaining treatment’ could arguably dictate that the use of GTN is not permitted (NHS, 2019b), and it is important that these last remaining wishes are upheld where possible (Blaber, 2012). The final consideration is that of justice (Beauchamp and Childress, 2001), and the impact that this could have on the patient, family and nurse in attendance. While administration of GTN may infringe upon the rights of the patient, withholding it may be interpreted by the nurse as undermining her clinical competencies (Zimmermann et al, 2008). Moreover, the family may feel that the suffering of their loved one is not being adequately addressed in the absence of clinical intervention. Lim (2016) argues that surrogate decision-makers such as family members are emotively-driven, and that any such request may represent their own preferences and arguably not those of the patient. In an effort to mitigate such factors, effective and responsive communication techniques and empathy were maintained throughout when conversing with all parties (Caroline et al, 2014). By explaining the decision to not carry out any form of treatment, including the administration of GTN, the student paramedic is empowering not only the patient, but the family and nurse in attendance as they collectively feel involved in the final decision of care (Alder, 2013).

This individualised approach is in keeping with paramedic decision-making responsibilities as autonomous health professionals (HCPC, 2019), and embodies the sentiment that ‘withdrawal of treatment does not equate to the withdrawal of care’, with the paramedic advocating for the patient at every stage of care across the life span (Bench and Brown, 2011).

Conclusion

Having considered and critiqued some of the key concepts in clinical decision-making, it is clear that such a multifaceted process is not linear in its make-up and should therefore not be self-contained within a singular framework. Instead, the paramedic should incorporate varying levels of insight from experience, intuition, reflection and ethics when forming hypotheses. Moreover, consideration for external and influential factors such as the presence of loved ones, multidisciplinary teams and, most importantly, the patient's wishes should be taken into account to ensure a holistic, and individualised approach to clinical decision-making.